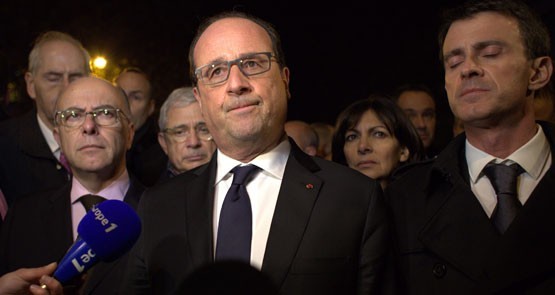

French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve, President Francois Hollande and Prime Minister Manuel Valls speak to media after the attacks

Of the seven attackers killed in the Paris bombings and shootings it would so far appear that two were foreigners, while at least three have been confirmed as French citizens. Meanwhile, a Syrian passport found at the Bataclan concert hall, which suggested a refugee as a culprit, is reportedly fake.

Though there seems little doubt that Islamic State authored the atrocities — a communique from the group speaks of “dispatching” eight jihadis to wage war on “crusader France” — there’s no indication that disguised refugees smuggling themselves in on the wave from Syria were essential to the plot. Whatever instructions may have been passed from central command in Raqqa, it appears that the three teams that attacked the stadium, the Bataclan hall and some nearby restaurants did so largely as autonomous groups.

The attacks were pretty crude — luckily, as this meant that three suicide bombers didn’t gain access to the stadium — and pretty simple. The object was civilian terror in its near-purest form — people were murdered simply for being on French soil. One of the restaurants targeted was Cambodian, so it would appear there was no attempt to target white Europeans, crusaders. They were attacks that mobilised the pure heart of terror, indifference to innocence.

They have certainly succeeded in it, largely by mixing the techniques of bombing and shooting. The latter, in the Bataclan hall, had the same ghastly theatrical quality of an IS mass execution video — hundreds of trapped people were shot at one by one, 90 of them killed outright. It would seem to have become clear to IS and other groups that bombing is not as terrifying as it once was — shooting, one by one, is, as the sheer global horror at the stories that came out of the Bataclan attest to.

President Francois Hollande has said that the attacks amount to an “act of war”, and so they do. But from the point of view of IS, it is an act of further war, France’s bombing of Iraq and Syria being the original act of war to which they are replying. Here, IS can’t really lose. If Hollande were to treat these acts as merely criminal occurrences and argue that the state should be blind to the purported political motives of such perpetrators (as the UK tried to do with the IRA, or to Zionist terrorists in the 1940s), then he would appear weak in the current context.

But as soon as he declares it an act of war, he grants recognition to the Islamic State as such — as a territorial entity. By all material definitions IS is a state, with a government holding a monopoly of violence within its borders, enforcing law and collecting taxes from a functioning economy. What else is a state but that? This weekend, it just became a whole lot more real as one. It was understandable that people would want to “stand with France” by lighting up the Opera House and whatnot, but that also helps IS in its striving for recognition, as an “other”, with consequences. The global village that has finally arrived with the advent of Twitter makes the need to do something, to manifest, overwhelming. Terror relies on this, just as the terror of the ’60s and ’70s arose with the general spread of satellite TV and global news.

Yet of course, in another aspect, IS absolutely doesn’t need the territory to make a global mark. The West has entered a slightly punch-drunk phase for the moment, reminiscent of 9/12, 9/13, etc, when all sorts of phrases — “let’s roll into Raqqa” — are being bandied about. Well, that would not be so hard with a mid-sized force, 75,000-100,000 troops, who would have to remain for years to try and bolt something down. But that is, of course, an invasion of northern Syria, and a re-invasion of Iraq. That does not seem at all likely. But even if it were, whatever decapitating effect it had on IS would be the same as applied to a hydra. What better recruiting tool in the Muslim populations of Western countries than yet another invasion, another “remaking” of the Middle East, to “get it right this time”?

This would approach the effect that the British worried about in Belfast and Derry in the ’70s: that you can reach a tipping point at which people who are merely angry or disgruntled, politically resistant , etc, start to volunteer for “active service” (i.e. urban guerrillaism/terrorism) at a suddenly vastly higher rate, jumping from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 2000. When that really starts, you’re finished — as the British were finished in the Palestinian mandate, or the Isarelis in Gaza. But at least those entities had the option of withdrawal. In Western societies, multi-ethnic for half a century now, there is nowhere to withdraw to. There is no inside or outside to the people defined as under attack (and whose states, elsewhere, are doing the attacking). You can’t “keep out” the attackers by breaking the link between Raqqa and the West. The link is online and the degree of operational instruction required, virtually nil. And if IS was to be annihilated, the attack would prompt those new recruits to create free zones in north Africa, where another fully functioning territorial IS will arise at any moment.

The focus on keeping refugees out is thus an obvious fantasy — a fantasy that something can be done, at that level. But, of course, nothing can be. Another few of these attacks or worse, and it would be possible to tip into the next stage, where the large-scale roundup of Muslims begin. At worse, a state of exception would be invoked, and natural-born citizens would be summarily deprived of their rights. But that, in turn, would split European society in two. The last solution, and the one most likely to be applied, will be intense surveillance of a wider group of suspects, a practice that, we also know, turns suspects into more active violent people, by conferring the identity of such on them — “I will become what they say I am.”

Indeed, everything will be tried, in an effort to avoid the obvious truth: withdrawing troops and bombing runs from those lands would diminish the terror risk at home greatly. But to do that would be to not only acknowledge the folly and criminality of a decade of wars, but to also acknowledge that the terror has a political content, that it is not some wacky war for a global caliphate, or a nihilist assault. Nihilism might describe its means; it does not describe its ends. The Western powers are willing to keep offering non-solutions for quite a while, and for a quite a few more deaths of their own citizens, at the hand of their own citizens.

Leaving aside whether this was another false flag operation, it does have the useful benefit of legitimizing France closing its borders to refugees. A small price to pay?

Of course it might be worthwhile to ask Yazidis and Kurds and other minorities how they feel about being left to fend for themselves while we sit comfortably at home after stopping bombing runs.

Fantastic article Guy..our strategy is counter productive..All violence ours and theirs is terrorism..

“Mess Accomplished” should have been on that banner of Dubyas after the Iraq debacle..

dubious virtue

fair point. I didnt make clear that the fact of terrorism doesnt mean one should withdraw from action. And personally i believe the YPG should get air support (and the PKK as well).

But the simpler point is that our presence there makes terrorism vastly more likely – and yet everything will be done to avoid that clear fact.

Guy, you’ve done an excellent job over the years of covering up the fact that your Capitalist Media outlet has persistently excused terrorists with nonsense about the point that military action alone isn’t going to resolve the problem.

Any schoolkid who’s not intellectually-impaired knows that, which is why Australian Governments haven’t gone down that road, no matter how often you pretend they have.