A persistent belief in the politics of terror is that terrorism is an “existential threat”, not (as claimed by the likes of Attorney-General George Brandis) to Western civilisation per se, but to Western politicians: a demonstrated lapse in national security via a successful terrorist attack is taken to be profoundly damaging to the government under which it occurs, especially if it proves the government had been warned by security agencies to take steps to prevent it.

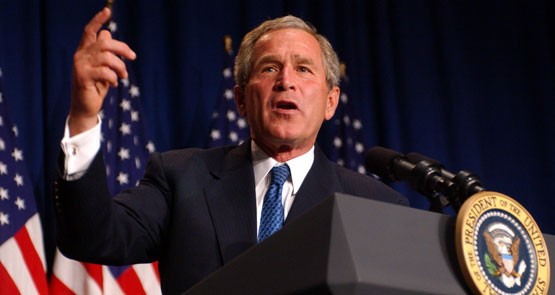

Political damage from terrorism, of course, is trivial compared to the actual loss of life and trauma inflicted by successful attacks, but as the case of George W. Bush illustrates, the political consequences of terrorism are a crucial contributor to the conditions for future terrorist attacks — either halting them or, as the West has done since 2001, encouraging them. Political decisions made by Bush after 9/11 ended up creating the environment that led to Islamic State and the atrocities carried out by its supporters.

And on close examination, it’s not clear that the belief that terrorist incidents are automatically politically damaging — which I’ve certainly held in the past — is entirely justified. Let’s consider the evidence.

Far from damaging him, the 9/11 attacks led George W. Bush’s approval ratings to soar; they reached an astonishing 90% in the Gallup poll in the immediate aftermath of the atrocities. It was only some time later that details began to emerge of how the Bush administration had ignored warnings about al-Qaeda and that there had been systematic deficiencies in intelligence gathering and security that enabled the attacks, but Bush was narrowly re-elected in 2004.

On the weekend, we learned more detail of a warning we first learned about in 2006 from the Bush-era CIA director George Tenet to Bush’s then-national security adviser Condoleezza Rice about a “spectacular” al-Qaeda attack against the US in the months before 9/11. Tenet proposed a plan to strike at al-Qaeda, but was rebuffed and told the administration didn’t want to hear it, that it “didn’t want to swat at flies”.

While the Bush administration is now synonymous with the Iraq War debacle — which has costs trillions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives and directly led to the emergence of Islamic State — its egregious, almost criminal negligence about 9/11 remains a little-known historical footnote.

Similarly, former UK prime minister Tony Blair’s approval ratings soared in the aftermath of the London bombings in 2005, despite the close connection between the bombings and Britain’s role in the invasion and occupation of Iraq (which, in the words of then-chief of MI5, “radicalised, for want of a better word, a whole generation of young people, some British citizens”).

Both examples suggest that, rather than creating contention about whether government actions or inactions may have contributed to the success of the attacks, instead they became rallying points for political leaders as the media, political opponents and commentators rushed to show “unity in the face of terror” and other cliches.

The 2004 Madrid bombings are a different example, though harder to interpret. The conservative Partido Popular government of Jose Maria Aznar was defeated at the polls three days after 191 people were murdered by an al-Qaeda cell, despite going into that election with a polling lead. However, the PP government had immediately sought to blame Basque separatists for the bombings, rather than give any credence to a link with Spain’s involvement in Iraq, and it appeared PP was trying to cover up evidence of an al-Qaeda link in favour of its preferred Basque narrative, which may have been more damaging to its electoral chances than the bombings themselves.

The impact of the massacre by Anders Breivik in July 2011 in Norway is also hard to assess. Then-Norwegian prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg, won plaudits worldwide by the calm, dignified way in which he led Norway’s mourning and response to the slaughter. But he lost office to a conservative coalition in 2013, including a far-right populist party of which Breivik had once been a member.

The Boston bombings in the US, on the other hand, had virtually no impact on the approval ratings of President Barack Obama (neither Rasmussen nor Gallup show any noticeable shift either way) despite Republican efforts — contrary to their “unite against terrorism” response after 9/11 — to blame Obama for the bombing.

It’s also hard to interpret the impact of the Lindt cafe siege in Sydney. It was in mid-December, so there’s no polling to determine whether voters rallied behind Tony Abbott — who responded to the incident with the sort of good sense that he would abandon this year after the first leadership spill — or were more focused on Christmas and holidays. But the persistent trickle of revelations this year that security agencies knew about Man Haron Monis — i.e. that Monis had written to George Brandis about communicating with Islamic State, and that this had been brushed aside by Attorney-General’s bureaucrats who then conveniently failed to provide Monis’ letter to the in-house government inquiry before misleading parliament and a Senate committee about the letter — appeared to register little with voters.

Admittedly, so many other things were going wrong for Abbott by that stage that it may not have mattered, but the governmental negligence regarding Monis would have dominated media coverage and prompted cries of “blood on their hands” from conservatives if Labor had still been in office.

January’s Charlie Hebdo-linked massacres in Paris, however, preceded a big rise in President Francois Hollande’s approval ratings, despite it being immediately clear that the perpetrators were already known to security agencies.

There are thus only two examples here where the link between political damage and successful terrorist attacks can be made — and the Spanish example is problematic given the attempt to obscure responsibility by the then-government, while the Norwegian example doesn’t clearly demonstrate a link between the incident and political defeat. In other incidents, even when there is possibly basis for criticism of government agencies, even when political opponents try to exploit the dead for political advantage, it’s hard to substantiate our sense that no politician can afford a terrorist event on their watch.

It depends on how they use them?

Excellent article Bernard. Just think what would have happened if Tony Abbott was still PM. He would have powered through the bullshit to announce Australia was at war with the entire Middle East. Seizing the advantage he would have announced the next election. Where he would have been voted in, in a canter. Terrifying isn’t it?

After the “GST Referendum Election” Howard was lined up for the Retribution Tango, along with Lee’s Democrats – but after 9/11 he was able to rush home to call an election. Then he, Ruddock, Reith et al had “Children Overboard” to play with, less than a fortnight before the election.

As for Bush and his neo-cons – look how they were able to use it, while ignoring the deteriorating health of the emergency services at Ground Zero?

Sadly this analysis is probably correct, but there is damage done to the politicians’ legacies. Bush and Blair are, if anything, now seen as far more responsible for the mess in the Middle East than they were previously. History will be brutal to them, I suspect.

Xoanon – I agree that history will view them harshly but I wish that we could award them the justice they richly deserve right now.

To paraphrase, “never let a terrorist attack go to waste” when there is power & electoral advantage to be harvested.

A bitter fruit.