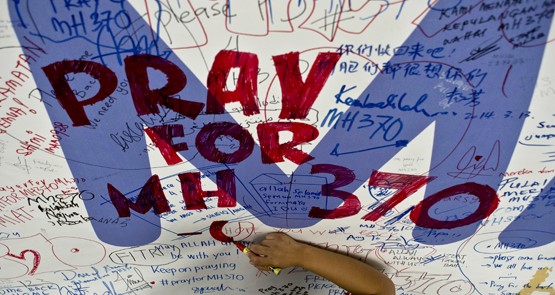

The Australian has become the last newspaper to discover that the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) thinks MH370’s pilots were incapacitated for the final hours of its flight before crashing into the southern Indian Ocean.

The ATSB has been saying that since late 2014, and, on December 3 last year it published a review of the data by the Australian Defence Science and Technology (DST) Group, which presented a set of factual reasons, supported by reasonable logic, for coming to that conclusion.

That detailed analysis is ignored by Australian veteran fighter pilot and airline captain Byron Bailey in his nevertheless interesting rehashing last Saturday of the position long championed by British pilot Simon Hardy.

Bailey falls for the frankly ridiculous fabrication by the media that MH370 was hijacked by its captain, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, who, according to this rumour, made the aircraft climb to 45,000 feet in order to kill the passengers and the rest of the crew by a deliberate depressurisation of the cabin.

There are several points to consider, without assuming Bailey is completely wrong or that the ATSB is completely correct.

The evidence for a climb to 45,000 feet soon after the jet was deliberately made invisible to air-traffic control has never been produced in detail. In fact, the claims as to this happening appeared to emerge in the media echo chamber in the early days of the disappearance.

Moreover, there are plenty of technical reasons well known to 777 pilots as to why such a climb would have been implausible at that stage of a flight, which was already at 35,000 feet, where depressurisation would have produced the same result without risking the rest of the alleged evil plot.

Such a climb would also have made MH370 potentially more visible to military radar across the border in Thailand. In terms of mass murdering those on board and exercising stealth, this claimed sequence of events doesn’t make sense — although criminal behavior doesn’t necessarily follow sane, logical and premeditated steps.

The Australian report doesn’t say what Bailey thought occurred to disable the transponder on MH370, which identifies aircraft to the air-traffic control systems. This doesn’t make his story wrong, but it would have been useful to know if he thinks that the captain accessed the below-floor electronics and electrical distribution bay via a hatch in the floor immediately behind the cockpit to perform other functions at various times that would have assisted his alleged plan.

The question as to what the state of the recovered flaperon — part of MH370’s wing, recovered on La Reunion island in July last year — tells us is important, and probably unresolved. Bailey misrepresents through emphasis elements of the DST report that the ATSB released with its recent comprehensive update. That report says the final incomplete ping sequence received by the Inmarsat satellite supports an out-of-control fall to impact on the ocean surface after the second engine flamed out and suggests that, at one point, the aircraft became inverted, losing line of sight with the satellite.

The inference that report draws is that if a pilot were attempting to make a controlled ditching of MH370 he would do so when there was sufficient fuel remaining to provide full power and operability to the controls. It is a reasonable inference, making the exact state of MH370 in the final stages of its flight something reasonable readers might consider unresolved.

Many experienced airline pilots say that too little is known with precision about the loss of MH370 to start taking sides as to who did what to the 777-200ER, which was on its way from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on March 8, 2014, when it vanished.

If he wants to continue with the claim that MH370 was made to climb to 45,000 feet, Bailey ought to produce conclusive evidence to support this media rumour, which ran concurrently in March 2014 after the disappearance, with one report claiming the 777 flew close to the ground across the Malaysia peninsula. He also ought to deal with the sequence of events up to the loss of signals from the jet in detail.

One of the problems with the MH370 saga is the quite obscene taking of sides as to whether the jet was under control, or not under control, until the last minute, in the all but complete absence of any factual resolution of the details of the final hours.

All that we do know is that the Malaysian authorities seriously compromised their credibility in their variable and misleading narratives about the crash, even up to and past the recovery of a flaperon from the wing of MH370.

We can also conclude that Boeing, which has been advising the search, knows a thing or two about 777s, and has given excellent assistance in modelling and analysis of the various paths, subject to a range of conditions, that the jet could have flown on its way to an elusive location on the floor of the southern Indian Ocean.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.