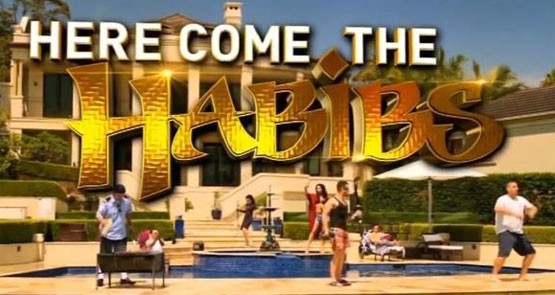

Channel Nine’s new comedy, Here Come the Habibs, looks very different to its normal white-bread line-up. The original fish-out-of-water comedy about an Australian-Lebanese family whose lotto win allows them to move to Sydney’s exclusive Vaucluse marks a definite departure for the network. It’s without doubt one of the most culturally diverse shows to air on a commercial television network in Australia. But if all Nine’s new comedy does is rehash the same old racist stereotypes about Lebanese people, is that really an improvement?

A public petition, started by Lebanese-Australian poet Candy Royalle, calls on Channel Nine to pull the show. While the show has yet to air, the trailer has left many highly sceptical. It’s not hard to see why. The trailer is cartoonish, filled with stereotypical trappings of Arab culture. The family patriarch is dressed in a singlet and sandals. His son is a weight-lifting meathead who thinks a $22 million lotto win makes his family billionaires. The women in the show appear exotic and vain, preening and shimmying around the house. The show’s highly exaggerated depiction of Lebanese-Australian culture comes in much the same vein as Pizza, which started airing on SBS in 2000. That’s not surprising, as its creators are Rob Shehadie and Tahir Bilgic, who both starred in Pizza and its movie spinoff Fat Pizza.

In Australia’s largely vanilla media, comedy has been one of the few areas where many non-white Australians have made their mark. Pizza remains the most widely known depiction of Lebanese Australians on our TV screens. For better or worse, Jonah from Tonga could claim the same mantel for Australians of Pacific Islander backgrounds (though star and writer Chris Lilley isn’t from Tonga and was performing in black face). More recently, TV comedies like The Family Law (based on Ben Law’s memoir) and Maximum Choppage (starring Lawrence Leung, which tells a fictional story of a young Chinese-Australian man negotiating the cultural expectations of his family in western Sydney’s Cabramatta) have explored growing up Asian in Australia.

These shows, which all aired on public broadcasters ABC or SBS, tread a fine line. While not all have been controversial, it’s tricky writing about race in 2016. Social media has given audiences the ability to organise and protest against depictions of minorities viewed as demeaning or unhelpful. Both Jonah from Tonga and Here Come the Habibs (incidentally, both comedies about minorities written by people not from those ethnic groups — Shehadie and Bilgic aren’t writers on the latter, just creators) have sparked protests from the ethnic groups they depict.

Speaking to The Guardian’s Token podcast in an extended interview on the controversy, Bilgic said people’s fear was what made them take the whole thing too seriously.

“People saw the trailer and it’s almost about their own insecurities … They’re scared. They’re scared there’ll be uprisings, upheaval, another Cronulla riots.

“Once they see the show they’ll understand that. This show is actually about taking the piss out of rich people. Rob Shahadi — one of the creators — his ethos was we don’t want the Lebanese family to look stupid. Over the top, yes. But that’s what Lebanese people love — they love to laugh.”

Poking fun at themselves is a way many minority groups have eased their way into Australian society. But in a post on her blog explaining her issues with the show as evidenced from its trailer, Royalle writes that that’s exactly the problem:

“Apparently, Australia’s humour is that larrikin behaviour of good natured laughing at each other. Well, who’s laughing at white people? On national television? Pandering to stereotypes which further racist experiences?

“Those same critics pointed to Chris Lilley, who uses black face and yellow face to play Asian, Tongan and other characters, as a comedian who laughs at everyone equally. This view is so incredibly flawed — once again, he is a white male poking fun at marginalised groups … For humour to be equal, history has to be equal, and that is, of course, not the case — colonialism, oppression and marginalisation ensure absolute inequality.

“‘Kath and Kim’ is another show used in defence of ‘Australian’ humour — this classist show poked fun at those in lower socio-economic circumstances (as does ‘Housos’). All this humour is based on othering — making fun of the marginalised, the down trodden, those that are outside the apparent ‘mainstream’ of Australia. And isn’t that the crux of Australian humour? Making fun of anyone not white, not middle class, not ‘normal’? Is that really the sort of humour we want to promote in this country?”

Comedian Aamer Rahman, half of comedy duo Fear of a Brown Planet, makes similar points about the role of self-directed humour in depictions of minorities in the media.

“Asimilation means being able to make fun of ourselves for the benefit of the majority,” he told Crikey. “Personally I think it’s massively out-dated.

“The generic idea of being able to take a joke is one thing. But the power imbalance that comes along with a majority demanding that of a minority is different … Why should we have to do that? Why should people have to prove acceptability in society by negating or mocking their own culture? It says a lot about what Australia requires from minorities in order to deem some part of them acceptable.”

Rahman says he doesn’t have a problem with humour drawing on race. But in his own comedy, the intention is important to him.

“If it’s racial, it’s about two different groups. So the question is, what is it ultimately trying to say about those two groups. Ultimately what position does the joke take culturally? Does it take the role that minorities are baffoonish, and only way to be accepted is by making fun of ourselves, or is it saying something that in dominant and mainstream culture isn’t said?

“I’m not opposed to ethnic comedy … But also a question of who’s listening to the joke. The audience is half of the joke. That’s the cultural context.”

Perhaps that’s part of why many are sceptical about Here Come the Habibs, particularly as it is airing on Channel Nine, not the multicultural broadcaster SBS. Given the trailer no doubt exaggerates and isolates the aspects of the show most likely to appeal to Nine’s broad audience, it’s not hard to see why some Arab Australians fear the show will laugh at them, rather than with them. Still, it’s hard to see Channel Nine having commissioned something like this a few years back. In fact, were it not for Stan, Netflix and Presto eating into the audiences of the commercial TV networks, Bilgic told The Guardian, it’s unlikely the show would have been produced at all. For the greater prominence it gives Australia’s diversity, does Here Come the Habibs constitute progress? Or is Australia merely finally catching on to the shallow, family-friendly comedies about race America pioneered decades ago with things like The Cosby Show? We’ll find out soon enough.

“Upper Middle Bogan” and “Soul Mates” (Bondi Hipsters) come to mind as examples of laughing at white people, on national television.

And as a member of the class “Kath & Kim” took the piss out of, I can tell you, few of us took issue with the lols. We were probably its biggest fanbase. I do take issue with being deemed so ‘marginalised’ and ‘downtrodden’ that I shouldn’t be able to see my world reflected in a humorous way on TV.

Really gives me the shits to see the legitimate points raised in this article and by Royalle contaminated with such self-righteous privilege-policing crap. The irony.

I’m still reeling following the portrayal of Tasmanians in “Bogan Hunters”. Is it a coincidence that it’s Lebbos & Turks behind these TV outrages?

Sounds like a cross between Beverly Hillbillies & Growing Up Gotti.

I’ll break the habit of decades and watch Ch9 just to see the first episode.

It sounds pretty awful but I found the Leb pisstakes in the Pizza series pretty funny and the Lebs probably did too. I remember an ancient working dog series where one of the dings in the crew took the piss out of his uncle’s awful house. I thought that was pretty funny and so did my ding mates.

And how do you take the piss out of rich people, we already know how horrible they are.

Yep, probably should follow AR’s intentions. And I’d suggest to Candy Royalle that she watch a bit more TV. Chris Lilley has taken the piss out of absolutely everyone, white schoolgirls even! Kath & Kim was people laughing at themselves. And even the short of the Habibs absolutely takes the piss out of the white neighbour next door.

Perhaps everyone should just loosen up a little.