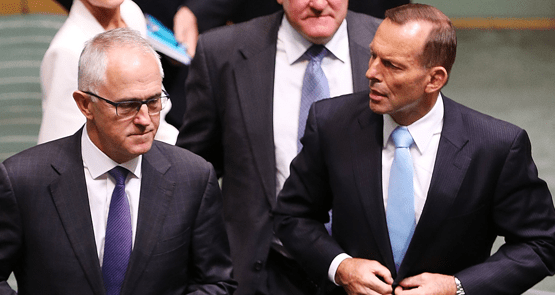

Given one of the primary goals of the Prime Minister’s savvy double dissolution ploy was to instil discipline into his restive backbench, the first results in the hours afterward were not promising. Demonstrating the well-honed Rudd tactic of making sure you ruin your enemy’s best moments, Tony Abbott chimed in from the other side of the world to declare that Turnbull was Abbott Redux.

Even the press gallery, many of whom had been searching through the thesaurus for new adjectives to praise Turnbull’s genius, had to stop and detail Abbott’s comments and Turnbull’s slapdown response. The Prime Minister, naturally, was disgruntled about having to publicly rebuke his predecessor when he wanted to use Monday’s announcement to re-energise his leadership.

The prime ministerial levels of gruntlement, of course, would have fallen even further once the media began mocking his “continuity and change” slogan — a tiny version of the now alarmingly widespread American problem that actual politics is now so absurd that satire is not merely dead but buried and cremated as well. Then again, better to steal from Veep than from a wretched Michael Douglas film like Labor’s Anthony Albanese did.

To Abbott’s credit — and this is a point made by a number of Labor people — he is not really using Kevin Rudd’s approach to destabilisation, which was to do it on background, and via proxies. Abbott’s doing it in full public gaze. His sleight of hand instead is to use language that appears to praise the man who removed him but which is heavily and deliberately loaded with criticism. He knows full well his remarks declaring Turnbull merely a continuation of himself will end up on Labor billboards. He understands that his apparent attacks on Labor’s tax policies are read as specific warnings to Turnbull to not consider adopting anything like them.

As a result, Turnbull has been forced to articulate more clearly the differences between himself and Abbott. He visibly struggled to do that on Monday night when asked to do so on 7.30, feebly offering the media ownership laws — which may well not be passed this year anyway — and having a cities policy (downgraded since Jamie Briggs quit) as key points of difference. This morning, as if desperate to further demonstrate his distance from Abbott, Turnbull unveiled the retention of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (and some redirection of existing funding for renewables and energy efficiency). Abbott had sought to abolish both, although bizarrely he ended up boasting about the CEFC as an example of what his government was doing on climate change.

Both bodies are examples of the kind of interventionist, big government approach to climate action favoured by this iteration of the Liberal Party — in which winner-picking by bureaucrats is favoured over market mechanisms like an emissions trading scheme. As Turnbull knows better than anyone, it’s a more expensive, and less efficient, form of climate action than market mechanisms of the kind he now rejects. Still, not actively engaging in a war on renewable energy does indeed make a point of difference with Abbott.

The curious thing about Abbott’s destabilisation, however, is that it isn’t making him any less popular with Liberal voters. Yesterday’s Essential Report contained a rerun of a question asked in December: what should Abbott do? Forty seven per cent of voters thought he should resign now or at the coming election. But only 32% of Liberal voters think he should quit — and that’s down from 37% in December. The very people who you would expect to be most concerned about his destabilisation of Malcolm Turnbull are now more enthusiastic about Abbott staying in politics.

One characteristic of Tony Abbott — regardless of the complete hash he made of the prime ministership — is that he is perfectly in tune with the Liberal Party base, which is far older, whiter, more male and more reactionary than the rest of the community. Malcolm Turnbull, on the other hand, might be more electorally appealing but has a constant challenge in trying to keep the Liberal base happy. And judging by those numbers, Abbott’s destabilisation of his successor is not being viewed critically by the party’s supporters, no matter how much it might upset his parliamentary colleagues.

On that basis, it might not be very realistic to expect Abbott to stop any time soon.

Bernard, Your last paragraph is gold! i.e. “One characteristic of Tony Abbott . . . . . . “

“Both bodies are examples of the kind of interventionist, big government approach to climate action favoured by this iteration of the Liberal Party — in which winner-picking by bureaucrats is favoured over market mechanisms like an emissions trading scheme.”

Well, not really BK. CEFC is for making loans and investments in going concerns, and despite claims of it costing us money, was actually making money for the government.

The AREA is largely about regulation, not picking winners.

Your ideological slip is showing, and if anything has been proven over the last 30 years, it is that markets are not the most efficient way of doing much of anything, they are only a way of doing things, and are as subject to cronyism, corruption and outright rorting as any other mechanism.

Hmm … The Del-Cons (delusional conservatives) are alive and well and excitedly pushing their extremist views through their mouthpiece … the ex-PM …

“He {Abbott] knows full well his remarks…”

Nikki Savva has made it crystal clear that Abbott has a tin ear for politics hence Mummy Credlin edited and controlled his every utterance. When he did escape her apron strings we all laughed at him, or not.

Abbott has been either protected by grotesque mother substitutes, or indulged by tinfoil-hatted old fogies all his life. He has no inhibitions, which many find hilariously charming, and lacks the maturity to foresee consequences, which are problems for someone else to solve.

So expect more of this from Tony Abbott until someone runs over him…

Of course, this announcement is spin, and most of the media have swallowed it hook, line and sinker. Had Turnbull been honest, he would have explained that he was taking $1.3b from ARENA, and redirecting $1 billion of it to a new body, with a budget of $100m per year over ten years, to provide loans for various (politically motivated?) projects. However, on the plus side, Abbott wanted to take all of it.