The government’s political package to solve the problem posed by Labor’s call for a banking royal commission will leave the systemic problems of lack of financial sector oversight unaddressed.

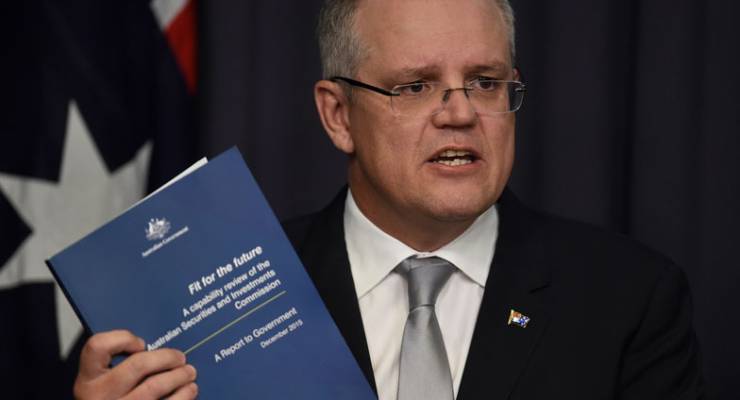

This morning Treasurer Scott Morrison and Assistant Treasurer Kelly O’Dwyer announced a hastily contrived set of changes to beef up the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. The $120 million funding cut from ASIC’s budget will be restored via a levy on the banks, but only half of it ($57 million) will flow into additional operational funding, with the other half to go into capital spending for “enhanced data analytics”, meaning only around half of the several hundred staff cut from ASIC in recent years will be restored.

The package also involves a new ASIC commissioner to focus on investigating financial sector misconduct, the re-appointment of current ASIC chair Greg Medcraft for 18 months (his term was due to expire in May), and the removal of ASIC from the public service requirements relating to industry consultants. ASIC will also collect all its costs from industry, ostensibly making it less dependent on government funding decisions.

There will also be two more reviews — one on “ASIC’s enforcement regime, including penalties, to ensure that it can effectively deter misconduct” and another on dispute resolution and complaints handling schemes.

The package was prompted by Labor’s call for a royal commission into the banking sector in the wake of repeated scandals by the big banks and the current prosecution by ASIC of ANZ and Westpac for interest rate-rigging. ASIC, the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority and the Reserve Bank have all, in recent months, criticised the culture of the banking industry. At least two polls have found strong community support for a royal commission.

Today’s package meets the first political hurdle facing the government — restoring the funding it has cut from ASIC over the last two years, albeit with not all of it flowing into operations — but will do virtually nothing to address the major problems with financial sector oversight identified by a major inquiry into ASIC in 2014 by Labor, independent, Greens and National Party senators.

That committee — which examined the operations of ASIC before its budget cuts — found that the regulator was timid, inept and too willing to take the banks at their word. The committee also devoted a chapter to the flaws in Australia’s approach to corporate whistleblowers — after ASIC itself had admitted it had mishandled whistleblowers who brought to it key information about bank misbehaviour. The committee’s belief that “a strong case exists for a comprehensive review of Australia’s corporate whistleblower framework, and ASIC’s role therein” has been entirely ignored by the Coalition since then.

As Crikey reported in the months after the committee report, Australia fares poorly when it comes to private sector whistleblower protection, despite a good framework for protecting public sector whistleblowers. The committee recommended a long list of reforms to widen Australia’s existing, very limited protections for corporate whistleblowers, better protecting anonymous disclosures, making it easier for whistleblowers to access legislative protection, and most of all addressing the bane of all whistleblowers, the career-damaging and career-ending repercussions of being identified as a whistleblower, both through greater punishments for companies that take reprisals against whistleblowers and, potentially, a US-style whistleblower reward scheme.

Whistleblowers being sacked by the companies that expose for wrongdoing is routine — for example, CommInsure’s chief medical officer, Dr Benjamin Koh, was sacked just days after revealing a systemic refusal to pay legitimate insurance claims by the Commonwealth Bank’s insurance arm. Today’s package has nothing on whistleblowers, leaving Australia with a substandard whistleblower protection system that internationally ranks even below that of China.

Another area of concern is that ASIC will be freed up from restrictions relating to public service secondment of employees from industry, pitched by Morrison and O’Dwyer as better enabling ASIC to go after banks. In fact, such secondments raise very serious concerns about industry capture of the regulator and were the subject of recommendations by the committee in light of the evidence of James Wheeldon, a former ASIC employee.

Whether the package will be enough to assuage community demands for greater regulation of the banks remains to be seen, but today’s package looks very much like that of a government that bent over backwards to deliver a win for the big banks on gutting the Future of Financial Advice reforms, takes generous donations from the major banks and has avoided any Murray Inquiry recommendations that upset the big four.

RC into banks ? Bonanza for lawyers, huge cost to taxpayers, and within a few years back to square one screwing the customers.

Better to force each major bank to accept a resident ombudsman, maybe 2 or 3 even.

having total power to investigate any aspect of the bank at any time, no exceptions.

Keating might have had the guts to do it, present pussy in command not so likely.

Resident ombudsman is a good idea, but I’d think that would be the sort of thing that a RC would need to recommend.

Wait till a few bank CEOs have to get into the witness box and voyage to the far shore of Amnesia. That will tell them they’re not above the law and make them focus very hard on probity.

Too restrictive, Richard…there wouldn’t be enough public knowledge about what was going on.

One…or even three…”resident ombudsmen” could be undermined/bought by the banks, especially if they were appointed by their mates in the Coalition.

Let’s have an RC…then deal with the findings. Much more useful.

The latest brainfart from this government? ANYTHING to protect their mates!!

It seems that Scott Morrison and Kelly O’Dwyer the wizard from Higgins are setting up ASIC to keep performing at the abysmal level of the past. It’s not as if ASIC will cease to operate as per usual if and when a Royal Commission is conducted into the banking and financial industry. Meanwhile the LNP muppets are only just refinancing ASIC with the funds that were cut when they came to government. The financial service industries scandals will continue whilst ASIC is at the wheel.

The most telling thing is the re-appointment of Medcraft, when his term would be up in May. Surely a sufficient face-saver for him had they been serious. That litmus dip says they’re not.

Labor can’t believe it’s luck. I don’t know why Shorten bothered to get out of bed this morning.

Who’s going to be paying this tax? Wouldn’t be punters picking up the bank’s tab?

“Trust us!”? After the last election?

How long would it be before they cut back, again?

A RC should look at why ASIC was bumbling around like a blow-fly in a bottle.

….. And all those vaults – what better place for skeletons?

I guess that ASIC are actually doing a good job. They are doing the job they were originally put there to do. To make sure that nothing ever happens or changes. Over to you, Sir Humphrey.

There may be no shortage of words about the issue, but sadly there’s an extreme shortage in the Crikey Commissariat Den re understanding what does and doesn’t need to be done.

Your continued misunderstanding of what the word Commissariat means is astounding in one so gifted. Some might think you are just a blowhard.