The Chinese Communist Party has always seen organised religion as a threat to the party, both by dint of the networks that it creates and the way that it divides loyalty to the state. The party’s propagandists have done an expert job over the years of so completely conflating the organisation with the notion of China itself that to criticise China is to implicitly criticise the Party, and vice versa.

Since the triumph of the Communists in 1949, religion has officially been banned, and China has spent the past 66 and half years as an officially atheist country.

In recent years, religion, from traditional Buddhism and Daoism to Christianity — in many ways filling the void left by the cult of personality around former leader Mao Zedong — has been tolerated, up to a point.

But with the ascension of Xi Jinping to the Chinese leadership, that point, if you like, appears to have been reached.

Xi has been on a program of asserting a tighter grip over the Chinese society, targeting both dissent inside the party via his so-called anti-corruption campaign and outside the party with a harsh crackdown on activists, rights lawyers and NGOs — a group that can be characterised broadly as a major slice of civil society.

Religion and its attendant spirituality is Xi’s latest target. This is particularly true of Christianity, which also fits in the “anti-foreign forces” theme of Xi’s nationalist narrative.

Little wonder, as Christianity is booming in China. Estimates range between 60 million and 100 million faithful, with a split of about 4:1 between a multiplicity of protestant, largely evangelical groups and Catholics. There are also upwards of 15 million adherents of Islam, a small but politically significant group in some north-western provinces.

There is also a split of about 50/50 between the “official” government-run churches — the protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement and the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association — and the much harder to quantify underground, or “house”, churches in many different protestant denominations of the faith, including a significant underground Catholic church.

In late April the CCP convened its first top-level summit on religion in 15 years. It was delayed by almost six months, due, observers believe, to internal disputes on how to deal with the surging appeal of religion in a country that is still officially atheist.

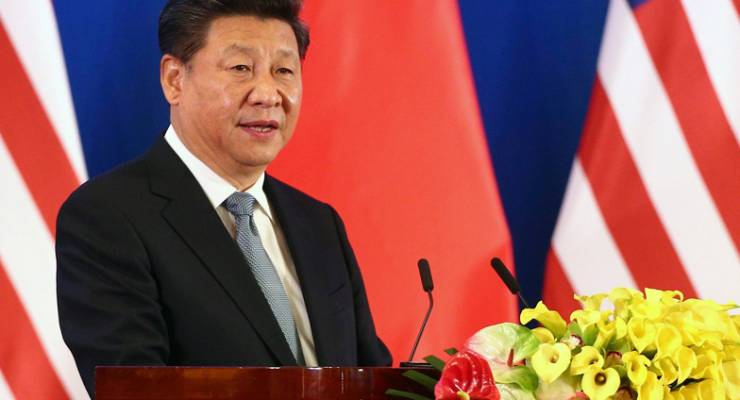

The closed-door conference in Beijing was headlined by Chinese leader Xi Jinping and his chief lieutenant, Premier Li Keqiang. In fact, only one of the seven-man ruling Politburo Standing Committee did not attend the two-day event — a roll call unprecedented outside the schedule of regular official party meetings and the odd funeral of important cadres.

In parts of his speech released to the pubic, Xi stated at the that the party wanted to “merge religious doctrines with Chinese culture, abide by Chinese laws and regulations, and devote themselves to China’s reform and opening up drive and socialist modernization in order to contribute to the realization of the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation”.

“We should guide and educate the religious circle and their followers with the socialist core values, and guide the religious people with ideas of unity, progress, peace and tolerance,” Xi said.

Put simply, the party wants to “Sinicisise” religions in China, particularly foreign religions like Christianity and Islam.

The summit came on the back of an often vicious, two-year campaign to tear down crosses — and even churches — in the province of Zhejiang. By some estimates more than 1700 building have been affected. As the campaign intensified, prominent pastors and Christian lawyers representing the interests of churches that had been demolished or had crosses removed were detained and later released (there have even been some mysterious deaths of clergy), as a clear warning not to meddle in the government’s program.

The big question is: what happens next?

It’s worth noting that Xi was once party secretary of Zhejiang province, and a number of commentators have suggested that the party has used Zhejiang as something of an experiment to see what it might execute on wider scales. Ahead of the conference Xi reasserted the ban on party members practising religion and extended this to retired cadres — anecdotal evidence says that there are not inconsiderable numbers of party officials who are also practising Christians.

While a national cross removal campaign is not widely expected to take place, authorities are thought to be looking at a range of other tactics, especially related to the finances of religious groups and links they might have to overseas religious groups. This is particularly true of the United States, where evangelical groups have close links to churches in China.

Already there are signs of a crackdown on religion in educational institutions across China, which had tolerated in some parts in recent decades. In mid-May, a video of kindergarten children reciting a verse from the Koran in the north-west province of Gansu went viral on the Chinese internet, and provincial officials were quick to re-establish bans on religion in schools. Christians now expect similar bans on ow level campus activities.

At the same time as the party is moving to exercise more control over the various churches, the Vatican has stepped up its effort at making peace with the Communist regime. Pope Francis is something of a Sinophile; one of his dreams is clearly being the Pontiff who can make a deal with China. But Xi’s priority of Sinicisation, and the Vatican’s aim of regaining control over the appointment of priests and bishops in the Middle Kingdom, will make this next to impossible to achieve without a major concession.

Xi’s campaign is likely to be further complicated by possible implications for an economy already showing signs of entering a prolonged period of slowing down when government stimulus is not applied.

Christian networks in China are all the more complex because many are business based. Nowhere is this more true than in Zhejiang, a wealthy province that lies just to the south of Shanghai and is part of the vast prosperous Pearl River Delta, home to about 120 million people. Other provinces, including the commercial hubs of Shanghai and Guangdong, also have similar widespread networks.

And any high-profile national campaign against Christianity will further antagonise the Unites States and potentially even Russia, as there are significant Orthodox communities still remaining in China’s north-east.

Not to mention the potential ill will that the party could garner from what is now a significant slice of the Chinese population.

All of which just might, despite its rhetoric, force the party to take its time and think hard about any serious action.

Good article. Xi in my view is not opposed to any religion as such – but he wants to ‘sinicise’, Chinese Christianity and Islam, i.e. ensure they are in line with Chinese claims to sovereignty and national values. It is very like Putin – who is luckier because he starts with a Russian Orthodox church that is already very ‘Russian’. For Xi, these churches and mosques are like foreign-affiliated NGOs are for Putin – to be mistrusted and watched closely as long as they are influenced by foreign money, favours, ideas and values. Actually the West has pretty similar views on Islam. Mosques are OK as long as they don’t fall under rich Saudi Wahhabi influence … Tony Kevin

The Chinese have a well-founded concern about the potential political power of organised religion – the Boxer rebellion were religiously based. This also explains their attitude to the Falun Gong. I think it is possible to distinguish their views on possibly closer links with Rome (whose churches tend not to be overly political, and if so, on the progressive side, and with a currently progressive Pope) with the evangelical churches in the US which are as much political as religious organisations, and in most cases extremely right-wing. You only have to look at the current Republican party problems in the US to see the danger that can be posed by these type of so-called churches.

The Chinese government should give conditional and reviewable operational licenses and tax all churches. These churches should be treated the same as any other part of the entertainment industry.

Why can’t Tony Kevin be a regular Crikey commentator on China?