One of the most recent opinion polls to land on our breakfast tables this week, the Essential Poll, suggests Labor is back in contention to win the federal election on July 2. Other polls have suggested the opposite. At the very least, after taking the polls’ margin of error into account, the two major parties appear to be heading for a photo finish.

Yet the betting markets, considered by some (by no means all) to be a more useful indicator of voter opinion than the published polls, suggest the Coalition government is going to romp home.

And when asked last month who they thought would win the election, more than half the respondents said they thought the government would be returned.

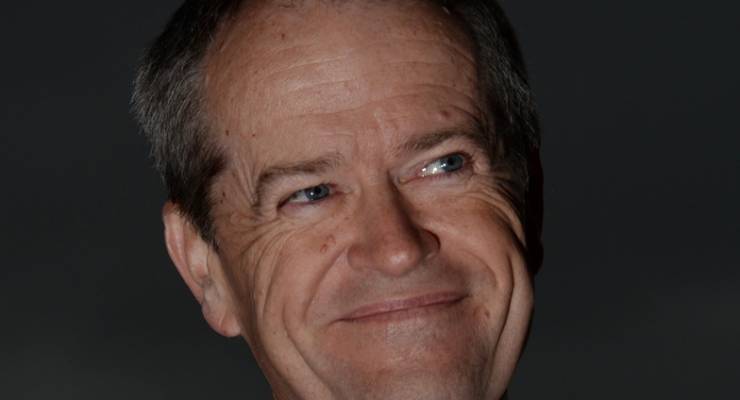

What gives? Labor has run a tighter campaign, and its leader Bill Shorten has been relaxed, on-message and even appears to be enjoying himself.

There have been some misjudgements by the Labor campaign team, and a couple of spontaneously combusting candidates, but to the interested observer there have been no obvious electorally fatal mistakes.

The answer to this conundrum requires, at least in part, a closer look at Labor’s success.

Campaign insiders from both the major parties are telling journalists that Labor is attracting increased support in safe Labor and Liberal seats, where the additional votes will make no difference to the election outcome.

This suggests Labor’s focus on building social capital over economic repair has played well to the party’s base but has not made a connection with swing voters in marginal seats.

As the Fairfax journalist Laura Tingle explained back in 2012, voters were conditioned during the Howard years to equate government spending that led to budget deficits and debt with irresponsible economic management.

Of course, in those years of never-ending surpluses, Howard was rarely criticised for his spending on middle-class welfare.

Kevin Rudd changed that in 2007, proclaiming “this reckless spending must stop”. But the Ruddster’s newfound parsimony lasted only until he was left with little choice than to spend his way out of the GFC.

The subsequent promises made and then broken by Rudd’s successor Julia Gillard to bring the budget back into surplus, further cemented the public’s view that Labor was good at spending money but had no economic discipline.

Even though the facts suggest otherwise, this perception remains today. And it would likely have been exacerbated by the government’s talk of Labor’s budget “black hole” and the opposition’s admission that it would have larger deficits than the Coalition over the short term.

[Are conservatives better economic managers?]

Given Labor had to reverse its opposition to a number of the 2014 budget’s “unfair” measures to improve its bottom line, it’s difficult to understand why the party didn’t wave the white flag on a couple more of the measures to ensure its deficits were at least lower than the Coalition’s. The public opprobrium would have been much the same, but Labor might have at least scored a few brownie points for effort.

But now voters in marginal seats, those who expect the government to be as careful with its budget as low- and middle-income households have to be, are apparently wondering whether Labor is the economic risk the government says it is.

And their conclusion will determine the election’s outcome.

In 2007 voters were convinced that electing Kevin Rudd was merely putting a younger, more progressive version of Howard into the Lodge. And in 2013 the community believed Tony Abbott was a safe pair of hands after the “chaos and dysfunction” of the Gillard minority government.

If Tony Abbott had remained as prime minister, we might have seen another cathartic ousting of a government this year.

Regrettably, for Labor, voters are simply disappointed with the current Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, but they are not climbing the ramparts to bring him down as they were with Keating in 1996.

And it would appear they’re not ready to trust Bill Shorten in the way they were prepared to do with opposition leaders Rudd and Abbott. (Perhaps those last two experiences have made voters wary.)

According to the Essential Poll, voters think Turnbull is more out of touch and arrogant than Shorten, but they also think the PM is more intelligent, capable, visionary, honest and trustworthy than his Labor counterpart.

Considered alongside the Coalition’s reputation as a superior economic manager, this voter confidence in Turnbull’s capabilities is driving the perception that the government will be re-elected.

It might be unfashionable in this post-Piketty environment to reduce the opposition’s electoral prospectivity to its perceived economic credentials. But that is what many voters do, and it would be denying political reality to insist otherwise.

[Labor offers the same lazy fiscal policy as the Coalition]

Of course the brilliance (or not) of Labor’s large-target strategy will be determined retrospectively by the election outcome.

If it ultimately fails to secure enough seats to win government, as Kim Beazley did against Howard in 1998, Labor may regret spending much of the past parliamentary term talking about the government’s unfair policies.

Instead, it should have spent more time explaining how health and education spending can, and does, deliver a strong economy and economic benefits to the broader community.

This article argues that increased support for the opposition in safe Liberal and Labour seats but not elsewhere “suggests Labor’s focus on building social capital over economic repair has played well to the party’s base but has not made a connection with swing voters in marginal seats.” But if Labour’s retrievable “base” can be found in safe Liberal (as well as Labour) seats, why can’t it also be found in the marginals?

To me, the relevant point is that voters tend to know whether their seats are marginal or not. Accordingly, they know whether they can lodge a protest vote without changing the government. (This also seems to me the most likely explanation when governments get back in with less than 50% of the two party preferred vote – rather than better targeted campaigning, or whatever.)

It also seems to be the case that swings in the marginals are usually preceded by swings in safe seats, and sometimes don’t emerge, if they are going to at all, until election day or very close to it.

Unfortunately the Coalition versus Labor economic debate ignores the Mainstream media –ignored Elephant in the Room matter of Carbon Debt in which pro-renewables Labor does better than the anti-renewables Coalition and the anti-coal Greens do vastly better than the pro-coal-exports Lib-Labs (Coalition and Labor). Thus the much-discussed Australian gross national debt was $406 billion in January 2016 and net government debt was expected to be about $278 billion in mid-2016 . Australian Federal budget deficits are presently about $40 billion annually. The Australian net government debt was zero in the 2006/07 year, the first time in three decades. However The Rudd Government introduced substantial government indebtedness in its lauded response to the Global Financial Crisis that enabled Australia to avoid recession. Assuming a damage-related Carbon Price in USD of $200 per tonne CO2-e , the World has a Carbon Debt of US$360 trillion that is increasing at US$13 trillion per year, and Australia has an inescapable Carbon Debt of US$7.5 trillion (A$10 trillion) that is increasing at US$400 billion (A$533 billion) per year and at US $40,000 (A$53,000) per head per year for under-30 year old Australians . Future generations will have to pay this inescapable Carbon Debt or suffer horrendous consequences e.g. cities will have to be drought-proofed at enormous cost; coastal towns and cities will have to be protected by giant sea walls or drown… (see Gideon Polya, “Climate Criminal Coalition Government Lying Endangers Australia & Planet – Australians Must Vote 1 Green And Put The Coalition Last”, Countercurrents, 17 June, 2016: http://www.countercurrents.org/polya170616.htm ).

“Yet the betting markets, considered by some (by no means all) to be a more useful indicator of voter opinion than the published polls, suggest the Coalition government is going to romp home.”

As someone who has spent a bit of time gambling, and has numerous friends who are deadset gamble-aholics, the main point here is that journalists don’t understand numbers and have no idea about betting markets. The key point is not that gambling sites are better indicators of anything other than the question ‘who do you think will win’, not by how much, so a 1 seat win will pay out, and most people expect that the Libs will be returned with a much reduced majority.

And equally, for Labor to win, and that is the only market being set, either Liberal or Labor (check your betslips, most are actually about who gets sworn in as PM, not which side wins) , sorry, yes, for Labor to win, nobody really thinks they will get in on their own right, but may well do in a hung parliament.

Further, even if only 49% thought Labor would win, and 51% LNP, that may and usually does lead to the money getting on the favourite far beyond the 49/51 odds. The bookies then need to entice people to vote for the underdog, so they blow the price out further to balance their books. In most cases the bookies aren’t making bets, they are taking them, and will win most of the time because they balance their betting books as far as they can.

And finally, I doubt that anyone thought Tony Abbott was a safe pair of hands after Rudd/Gillard. People just wanted to see the back of them, nobody wanted Abbott, still don’t. I also don’t buy into the baseball bats theory regarding Paul Keating, I suspect that was just one of those myths that became legends and then factoids, but I don’t expect that I will convince anyone of that argument.