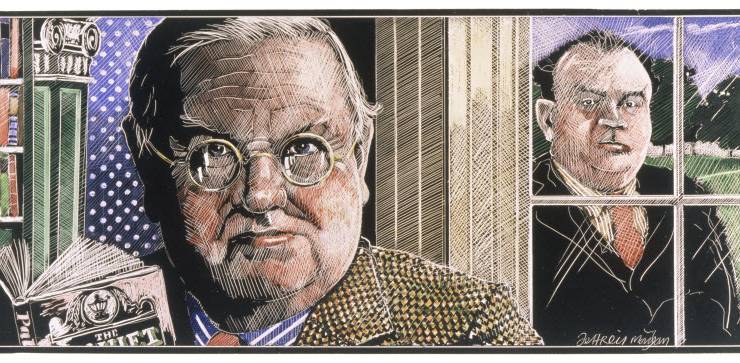

A portrait of author Evelyn Waugh and magazine editor Cyril Connolly

Paris, leaving again. And again, that means re-shelving dozens of books in the walls and walls of volumes in the flat, in the ninth, just up from the Opera, rented mainly for those books. Doing so, I realise that I have spent weeks reading, again, about Cyril Connolly and the London smart set of the 1940s. How many biographies of Cyril Connolly can there be? They appear to be writing themselves anew, just as I finish the last. Connolly was a fat, lecherous magazine editor — Horizon, founded in 1939, three months after the war began — who resorted to hackwork after he could no longer face the drudgery of magazine running. There is a famous photo of him, standing, looking, despairing, out French windows. I am holding a book with that photo on its back cover, as I try and find the place for the book, in shelves running perpendicular to French windows. Music from far off, coming through the window, direction of the Louvre.

Connolly’s circle were the Brideshead generation and beyond — Waugh, Acton, Brian Howard, Anthony Powell, Orwell, many of them Eton and then Oxford, the sixth form of one powerful school setting the British literary agenda and, to a degree, ours too, for decades. And the outsiders, Julian Maclaren-Ross, the king of the bohemians, Barbara Skelton, the most appalling man or woman in London, Paul Potts, the obsessive broadsider, a bad poet, and aphorist of brilliance,* and Sonia Brownell, the “Venus of Euston Road”, a woman of striking beauty, an artist’s model, and lover, for the painters of the Fitzrovia school, who put herself forward to edit a painters’ number of Horizon, and became, at age 21, its secretary, and by 26, its de facto co-editor, as Connolly slid into the warm bath of sloth and failure he had sought for decades, attended by a carousel of exasperated lovers.** Never Sonia, though, her brown hair shining, her eyes doll-wide.***

Thwarted by nerves and self-criticism from writing fiction herself, she explodes through the fiction of the era and beyond. Has anyone ever been more memorialised? Sonia Brownell is Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Mona Templar and Ada Leintwardine in A Dance To the Music of Time, part of Paula Maureil in De Beauvoir’s The Mandarins (courtesy of an affair with Merlau-Ponty, the philosopher), she is in The Sword of Honour trilogy, Connolly’s unfinished novel Deathbed Visits, in Angus Wilson’s Anglo-Saxon Attitudes, minor Koestler (they were lovers), and all through Maclaren-Ross, who was obsessed with her to the point where he was banned from the Horizon office. He wrote her into a pulp novel which, Julia aside, may be her most enduring presence, for it became a model for a certain type of unattainable, intellectual, rose, thorns close to the bloom, at the centre of half-a-hundred gangster flicks.

Cyril never got Sonia; George did, his worship of her, it seems, arising from a one-week affair. She became Sonia Orwell, 14 weeks before his death. Her many enemies slated her as a gold-digger. Powell and Lucien Freud (another … OK, it was a bohemian set) set the record straight: Orwell had said he would probably live if she married him, “and what could I do?”. She was swindled of his royalties; she co-edited the four-volume collection of his key journalism, letters and diary entries, insisting on its mash-up of all three forms together, rolling through the years, making the book a landmark, an epoch-memory, an inexhaustible pleasure. Released in 1968, it gave us the modern Orwell, made him in retrospect. She died alcoholic and penniless. Julia would appear to be the best portrait of her, capturing her two sides, fierce commitment to things mattering, life-giving contempt for rules, a cleaving to the sensuous, a recoil from it into the mind. Everyone fell in love with her. You fall in love with her just reading about her. Living women are jealous of this dead one. Make of that life what you will.

How the hell-? Ah yes, Francophilia. The whole Connolly set were mad Francophiles, seeing England as a drab, smug, philistine, distant outer-suburb of France, and they were forever dashing for the boat train for a few restorative weeks. For the Connolly set, the worst aspect of the war was being cut off from France, and the misery of that, and the end of his marriage to Jean, a “tomboy” dead of the drink at 40, stung him to write The Unquiet Grave, a linked series of aphorisms mourning the death of culture in the depths of a world war — which looked on the way to becoming unending war. Sly, feline, self-pitying, hysterical: “The id murmurs: if you collected women rather than books, I could be of some help”; “Hell is a nubile mother”;**** “The artist secretes nostalgia around life”; “The duty of every modern writer is to create a masterpiece. What writer, knowing that to be true, would not put away the half-finished piece of trash they are working on now?”; “Why do ants alone have parasites whose intoxicating moistures they drink and for whom they will sacrifice even their young? Because as they are the most highly socialized of insects, so their lives are the most intolerable”; “Inside every fat man is a thin one wildly signalling to be let out.” (Yes, that was his).

The Unquiet Grave, a bit of a sensation in 1944, was a plea for the virtues of self, for the limits of sacrifice. Horizon was intended as a commitment to that culture, of the unbounded cultivated self at a certain height. Ironically, it became the harbinger of something else entirely: its patron and art editor Peter Watson would go on to found the Institute of Contemporary Arts, from whence Richard Hamilton would invent Pop Art. In the first issue, Connolly had published Orwell’s essay “Boys Weeklies”, the first work of modern cultural studies. The Horizon crowd got government arts funding into Labour’s 1945 manifesto, and scholarships to art schools, that kids like John Lennon, Mary Quant and Pete Townshend would later take up, and put to their own purpose.******

Horizon ushered in the fusion of high and mass culture that would differentiate Britain from France finally and utterly. The Horizon crowd’s Paris was impossibly imaginary, a locus not for what Britain was not, but for what life was not. The real place had been crawling with betrayal and sycophancy all through the war; those executed for treason after VE day included a number of journalists and writers who had enthusiastically adopted Nazi values, not under duress or for survival, but for something to do, something to be. The Nazis had barely gone, when the rough justice and score-settling under cover of such began.

But knowing that that is all a parallax error, a trick of the light, does not make it any less persuasive. *****

France remains the fantasy, politically, for — and yes, I didn’t think we’d pull that Spitfire out of the long dive either — its aura of possibility in the new era. The British “solved” their post-war structural problems with the clean slate, Thatcherism. The French didn’t, and now they have to do something. But they have waited so long, that the moment of Thatcherite solutions has passed. Their reliance on borrowing from the future — virtuous private debt — is now exhausted, just as the accumulative powers of Western capitalism lurch into crisis.

Sections of the British working class were persuaded of the Thatcherite vision. Now, to keep them, the Conservative and Unionist Party of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is lurching into Chavez territory, or the image of such, with promises of energy price caps and worker representatives on company boards. That may work there. It won’t work in France, where Emmanuel Macron’s choice of prime minister — Edouard Philippe, from the centre-right Republican party — has sent things into uproar on the left.

[Rundle: heady hours for centrist France as Macron thumps Le Pen]

The “abstentionistes” in the second round are looking a little smug, some on the pro-Macron left a little sheepish, and angry at being humiliated by the choice of a right-winger to lead his government. Since Macron was of the left, he can claim it is the spirit of unity. The suspicion is that he would prefer a republican centre-right majority in the assembly, and this is his way of signaling that, in places where the En Marche movement — which seems to be called Modem now, I think a sort of pun on the “EM” way (Mode-EM), “En Marche is in fashion”, and of course the technocratic thang. It’s like they’re using Finnegans Wake as a playbook. Imagine Billy Bob Shorten making his way round that. His mouth would eat his stupid face. Macron might also want to encourage the Melenchonistes, which the move is certainly doing; he may prefer a hard-left opposition, to a centre-left one. What he won’t get is an easy ride …

***

To the Gare du Nord, late, hurrying through the Tenth. Black Paris, African Paris, is yielding to the white bohos of the 20th, to the northeast, and to gentrification coming from the south-west. On Des Petites Ecuries, “Au Bon Africa”, a rat-trap of a shop, spread over four fronts, pink-painted, holding 20 sub-let hair, beauty, nail stations, magazine pages pasted up, numbered model haircuts, christian rainbow stickers … the stations are gone, the shabby pink remains, so does the name, it’s an art gallery now, half-a-dozen nonsense works and around them, lean scruffy 20-somethings holding Heinekens, talking above the Senegalese wotsit music. We are the plague we are fleeing from.

Make it to Nord, and the gate, with minutes to spare.

“Bonjour. Je prends le 19.17.“

Premiere or deuxieme?

“Ni, ni,” I say, holding out my ticket. “J’ai une billet pour la voiture de l’Eurostar comme metaphore sur-utilise pour les transition entre les deux epochs, avec le temps historiques rendu comme espace socio-politiques des deux nations-etats.”

“Ah oui, voiture sept.”

Car seven was pretty crowded, the FT and Economist gals and boys in one corner working up their pithy anonymous opening paragraphs, “like the famous buffet at the Paris end of the Eurostar, enticing but leaving one curiously unsatisfied, the program of M.Presidente Macron … etc, etc”, a few people in the car’s first-class meta-metaphor section, they’d been riding back and forth for weeks without disembarking, to see what would happen. Nothing, as it turned out, which was pretty much what they were after.

I found a table seat, and set up. Pretty soon, un type slid in opposite. White fedora and suit, pinched face.

“Christ, you look like Peter Lorre cast in a Bernhard adaptation.”

“Hey, it’s your dream,” he sneered.

“Dream?”

“You’re still in the apartment, dozed off reading books you were reshelving. Do you really think that’s the best use of your time? There are two elections on.”

“Well in a way, yes. The trouble with history when it’s happening is that when you most need to be able to sit down and think through the real and the imaginary. But it’s the very time you can’t do that, because you need to see what’s happening. Yet in another way nothing’s happening.”

“Do go on, Meester …”

“Well look, nothing’s turned out as we thought. This was going to be the election where Le Pen slugged it out with everyone else, and in the end, though she doubled the Front National vote, she seemed to stuff up the campaign, and disappear quickly. Her niece, a Front National shiksa if ever there was one, has announced she won’t be going down the leadership chute. Can the party find another leader, or did its (un)holy family aspect hold it together …?”

“Meeeen … viiiiiiile …”

“Meanvile, meanwhile in England, Jeremy Corbyn may still lose big, but he appears to have shifted the debate leftward. Perhaps the whole Anglo-sphere leftward. Last week the Tories announced a cap on energy prices to households, after Labour announced that there would be a public energy provider competing with the privatised groups. Today, they’ve released a workers rights policy offering a year’s leave for the chronically ill, or carers of such, workers on company boards. A lot of it is sham, and a con, but a lot of it isn’t, it’d be stuff they’d be held to.”

[Rundle: Britain’s new left insurgency, though forceful, remains hobbled]

He kneaded the edge of his fedora …

“Aaaaaaaand …”

“Well, it means two possible things. One, the Tories have internal polling that shows them doing much worse than thought in key marginals, that the national polls reflect the ‘bumbling Corbyn’ image of the media — but that on the ground, the message about Teresa May’s cynicism and vacuity are beginning to bite, as is the idea of heartless Tories. The argument would be that the age of suspicion of the state is finally over in Britain. A knock-on effect of Brexit is that people want collective answers to problems again, so the flat-out determination to re-nationalise these bandit train companies, fund the NHS properly, are starting to bite — Labour helped enormously on the NHS issue by the weekend’s cyber attack, which hit the NHS hard because so many people had been pulled off admin to do direct patient care, so software wasn’t updated …”

“But zeee second …”

‘The other possibility is that the Tories are going for broke, promising anything so that May can get not only a clear majority in her own right for the Tories, but a de facto majority for her broad middle group within the Tories — Tories who were remainers, but have now converted to ‘hard Brexit’ out of political expediency. With 450+ seats, May would be approaching an inner-party group of 325+, enough for a majority in parliament every time. She could run government from cabinet, and rubber-stamp it in Parliament. Plus she’d have the workings of a super-majority, to override the Lords, make constitutional changes, change boundaries to remove Labour safe seats, and so on.”

“Zee two are not …”

“Exactly!” I thumped the table, proving it real, or an illusion of sufficiently transcendent character to make intersubjective acceptance of its extended character a necessary assumption of action in the world.******* “We have no idea anymore of how politics maps onto the masses, even when we poke and prod them with numbers and measures. ‘Left’ and ‘right’ are busted. People are so far from that framework, marooned, they can’t even think within its terms.”

We’d passed through the tunnel. The fields and farms and villages of France, yielded to south-east England, an enormous concrete sleeve/mesh/tarmac, a suburb of itself. The warm bakery smell had long since gone. A meaty tang filled the air.

I made the stranger get up, put on his hat

“And vot is zeeeee take away-“

“Kebab. It’s always kebab.”

“I mean …”

“I know. Well, in the opera, Cellini throws his life’s works into the furnace, to make the gold for one perfect creation, and that’s what the Tories are doing. Except for ‘gold’, read ‘shit’. It’s like a giant crapper, bubbling away. Sector price capping, state dictates to corporations … for the sake of one election, they have thrown out the whole classical liberal legacy that Thatcher put at the heart of their politics. That is desperation, or hubris, or simply such a total contempt for ideas, for politics as meaning something, for the public they’re appealing to that — well, we’ll find out.”

He vanished.

***

Music came under the door, through the air. La Marseilleise, revolutionary song whose lyrics are filled with horrifying fascism about soaking your fields with the impure blood of your nation’s enemies.

A half-eaten kebab lay on the bedstand.

“What’s that?” a floating voice said.

“It’s a kebab.”

“The music.”

“They’re inaugurating Macron. Why aren’t you there?”

“Another empty spectacle, Sonia, I can’t do them anymore. Am I in Britain, France or in between.”

“The Tudor Rose Hotel, near Paddington station.”

“Why is it so shit. Why is everything so shit here? I was going to mail some parcels in Paris. There’s a post office on every second corner. The system inside is a nightmare but … I hit St Pancras, and from Kings Cross to Green Park, near Buckingham Palace, there is not a single full post office. How is this possible? How can a society work like that?

“I …”

“Or take the kebab. In France, you want a snack, there’s a boulangerie, you buy a small quiche for two euros, it’s delicious. The principle being that because the food’s good, you don’t need too much of it. The kebab — in England there’s the kebab — is four quid of oily saddle meat dead lettuce and garlic sauce. Because it’s so awful, they give you more of it, as compensation. Think about that. Even better, they give you so much of it that it cannot be held in your hand. It’s a take-away you can’t take-away.”

“Yes I see.”

“None of this hangs together.”

“Oh, turn it into a triptych. Cyril did that all the time. Enemies of Promise.”

“‘I have always disliked myself at any given moment. The sum total of such moments is my life.’”

“Dear George wasn’t too kind about the Unquiet Grave.”

“‘That marvellous product of rentier capitalism, a private income with an inferiority complex’ … and that’s it really. Britain and France, they’re not two different ways of life. One’s a way of life, and the other is a ruins of one. Now people across the world seem to be waking up to what happens when you put the market at the centre of your way of life, and let it, encourage it, celebrate it, make its way into every part of the culture. The Tories are scrambling to hide the evidence of what role they played in it. The most successful political party in the west may win a landslide and undermine itself irrevocably at the same time.”

“Maybe.”

“Maybe? That’s the best line I can come up with for you? Why am I so obsessed with the doings of a bunch of bohos of the 40s, cut down by drink and arrogance and inferiority, vainglory and anxiety?”

“Aside from the sheer thrill, the dead live, lives and letters less marks on paper than dried fluids on sheets? Because that was the decade, that was the time when something was really possible in Britain. We got some of it, lost a lot of that, are by some measure the most benighted European democracy of them all. By a strange strange process these possibilities have emerged again. Socialism. Actual socialism? Who would have imagined?”

“I don’t know how to end this-“

“Just-“

***

*”I do not know what significance should be made of it but no one can deny that Hitler was a better husband than John Ruskin.”

**”I don’t mind you fucking other women, I just wish they’d feed you” — Barbara Skelton (Mrs Connolly number three), making soup.

***”I detect lesbian tendencies,” Connolly said, after she refused his advances. He called her an agent behind enemy lines, later the Violette Szabo of the sex wars.

****this may be a reference to Guy Burgess, of the Cambridge circle who was part of the Horizon crowd — as was Donald Maclean, a Horizon author — Guy blaming many of his own life troubles on having, one night, to rescue his mother from underneath his father, who had died in action, when Guy was around 10. When drunk, both Burgess and Maclean would joke to Connolly and co. about being spies for the USSR, more than a decade before they were rumbled. Ian Fleming was a contributor too. Moneypenny — the enticing Moneypenny of the books, not the joke spinster of the films — may have been based on you guessed it.

*****”A stick in the water does not look like a bent stick, it looks like a stick in the water,” as Freddie Ayer, house analytical philosopher of the Fitzrovia set had it. When asked what symbol would most evoke in him a picture of Paris, he replied “I would say, a road sign saying ‘Paris’.”

******Horizon’s independence was something of a fudge. From its inception, the government had favoured it, with money and a special allowance of scarce paper, as a valuable propaganda tool for gaining US support for the fight for civilisation against Nazism. Orwell’s creation of the “fiction department” in Nineteen Eighty-Four was based in part on this novel, soon to be standard, embrace of culture and the state.

*******”I am not in my body. I am the body in the world it makes”. Merleau-Ponty. No wonder Sonia swooned.

Wow! Vintage Rundle; worth persevering with to the end

LOL. Not sure you actually got the Spitfire out of the dive Guy.

But it *was* a fun read none the less.

Sometimes it’s better to just go with the plunge and drive it full speed into the hillside.

Why do I think that you could never write such – what should we call it – a passionately imaginative sociocultural political critique – about our own country. Is it that we lack the cultural history to tap into for this kind of performance or is it that we are still just a bland outpost, a happy-go-lucky little branch office of late capitalism?

Magnifique! I’ll be travelling to France and the UK for the first time next month and have been revelling in the Rundle dispatches, like a gonzo socio-politico-historical travel guide just for me. I will admit that the episode in the chip shop a few months back was disconcerting but GR always imparts a wonderful sense of emerging history, a front-row seat at _les transition entre les deux epochs_, which is almost as intoxicating as whatever he was imbibing while shelving. Merci GR, j’adore vôtre travail!

Ah yes, the chip shop that ran out of chips! Who can forget it.

Rundle, I’ve either ingested too many drugs or read another of your stream of barely consciousness wanderings. Either is good!

Super read.