Following the Sunday Herald Sun’s Future Melbourne series last month, Fairfax journalists Royce Millar and Ben Schneiders looked at population growth on Saturday and asked if Melburnians are “sacrificing the very things that made Melbourne a destination for so many in the first place?”:

“Beyond Spring Street a consensus is developing that we need something transformative in planning and transport to cope. The alternative is to ease the pressure, and that means slowing immigration. It’s a no go subject for many in the political class. But not for many Melburnians who are beginning to ask: how real are the benefits of this level of growth and how sustainable is it?”

It’s a long and well-written article that, if anything, tries to cover too much, but the key propositions seem to be:

- Melbourne is losing its liveability under the pressure of population growth;

- Property-related activity fuelled by immigration is the state’s de facto economic strategy; and

- It’s time to turn down the immigration tap.

It’s good to see The Age engaging directly in a debate about the appropriate level of immigration. It’s obviously an important public policy issue but too often sensible discussion is derailed by knee-jerk accusations of xenophobia or racism. That element will inevitably be present, but it shouldn’t be a reason to avoid debate.

But there are more than a few propositions in the article — some of them attributed to interviewees — that range from the doubtful to the arguable. For example:

The idea that Melbourne Metro is a lot of money for ‘not a lot of track’

Wrong: Metro is about increasing capacity and reliability of the entire system. It’s like building the foundations of a building: not visible, but essential. A similar point could be made about the removal of level crossings and upgrading signalling; no extra track, but a big improvement in the performance of all existing track.

The idea that the ‘World’s most liveable city’ gong is a proper benchmark

Again, wrong: the ranking measures cities in terms of their liveability for well-paid overseas executives on assignment; it’s not relevant to the average permanent resident, existing or new. That’s well known now, and journalists should cease quoting it willy-nilly.

The idea that Melbourne’s economy is primarily driven by immigration-fueled property prices

It’s harder to pin down the drivers of Melbourne’s economy because it’s now broad-based; it’s been a long time since it was manufacturing-based. Property is certainly important, especially in the short-term, but there’s much more to it. For example, Melbourne ranks 21st on the Global Financial Centres Index, ahead of places like Frankfurt, Dublin, Paris, Munich and Amsterdam. It ranks third on Forbes’ ranking of most popular cities for international students and second in the QS Best Student Cities ranking for 2016.

The idea that Melbourne could realistically retro-fit a ‘metro network like those in Berlin and Paris’

That’s unrealistic: Paris Metro covers an area with a radius of just five kilometres. It’s virtually all subway, it has 303 stations, and it services 2.2 million residents plus a huge number of visitors. Driving is hard because of narrow streets and very limited parking. That compares to Melbourne’s 28 stations and 0.43 million residents in much the same area. Melbourne can’t justify building a network that’s anywhere near as elaborate as the Paris Metro, but anything less dense and frequent will have a hard time competing with driving. Melbourne needs a transport system suitable to local circumstances.

***

Here are some broader issues I think should be taken into account when considering the issue of population growth in Melbourne:

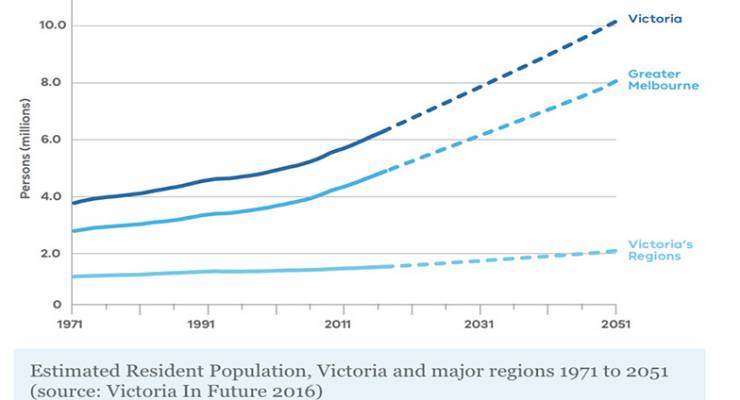

Melbourne can grow to 8 million residents in 2050 without collapsing into a dystopia

There are currently around 100 cities in the world with a larger population than Melbourne and about 40 with double its population. Some of the world’s most desirable and successful cities are already much larger than 8 million e.g. New York (21.4 million), London (10.5 million), Paris (10.9 million). Melbourne will necessarily be different at almost double its current size and there’ll be new challenges, but it’s wrong to assume it must be a disaster.

Immigration-fueled growth brings short-terms problems and makes some residents worse off

However, the evidence seems to be that, in the longer run, the average resident is better off. Bigger cities are more productive, more innovative and pay better. They offer more opportunity for both economic and social specialisation e.g. meeting people “just like you” (e.g. see here and here).

The implicit assumption that rapid growth inevitably means a significant loss of liveability overlooks the fact that cities adapt to the forces driving growth

For example, residents change the location of their job and/or dwelling, or they change how they travel, so that average trip times remain relatively stable. It’s invariably belated, but governments invest in infrastructure, improve services, and release land. Is Brisbane, with a current population of about 2 million, significantly more liveable than Melbourne?

It’s not inevitable or even likely that the ‘population boom’ will play out in line with the current projection

Australia has had plenty of localised population booms before. The resource booms in the Hunter Valley, Central Queensland and Western Australia all came with dramatic housing price escalation and glaring inadequacies in infrastructure. But they passed. It’s probable the same will happen with Melbourne’s boom before we get anywhere near 2050. Population projections at the level of cities over long time-frames are uncertain because they’re largely based on recent trends. Melbourne might well hit 8 million one day, but the timing matters; if it’s a long way in the future (Millar and Schneiders say government should be looking out to 2100) then unforeseen social and technological changes are likely to render current projections meaningless.

The challenge of growth in all Australian cities is largely political

It requires investing in infrastructure on a massive scale over a short time-frame; that necessarily competes with other important uses and means we can’t simply “build” our way out as politicians and many advocates like to claim. The biggest political challenge is to use existing assets more efficiently, e.g. roads repurposed for more space-efficient modes than cars; existing suburbs redeveloped at higher densities. It will also be necessary to do what all cities have done historically: continue to accommodate some growth at the fringe and/or in “overspill” regional centres.

Would migrants be better off not coming?

It’s important to consider if immigrants would live more sustainably if they stayed in their homeland compared to settling in Melbourne or in another Australian city or town. It’s also relevant to ask if their standard of living and life chances would be lower if they didn’t migrate.

The Commonwealth has a huge role in determining how well cities like Melbourne deal with growth.

It manages the level of immigration of course, but just as importantly, it controls the purse strings for infrastructure spending, and through taxation policy it shapes the demand — and hence, to a large extent, the affordability — of housing.

***

It’s pleasing to see some journalists from The Age make the effort to contact some new and well-informed observers on urban affairs, rather than resort to the same old wind-up reliables. It’s a pity though that the writers didn’t make the effort to explain the positive case for growth and immigration.

*This article was originally published at Crikey blog The Urbanist

Some of the research done for the Cities Commission may still be useful.

You haven’t addressed the issue of the great infrastructure, services and employment opportunities divide between inner and outer Melbourne, the complete lack of public transport in many outer areas, the times it takes residents of these areas to get to work. Cities like London, Paris and New York have extremely well-developed train networks. In the case of London which I have just visited, they keep adding to public transport all the time not just within the city boundaries but to commuter towns as well – unlike Melbourne which is still highly car reliant with no signs that this is changing. The new development around Battersea power station in London is having stations added as the development is built not vaguely planned for 20 years time and then only grudgingly as is the case in Melbourne.

As for Australia being popular with international students, is the motivation the opportunity to study here, or because it provides a pathway to permanent residence?

And what about the water supply to Melbourne during the next 13-15-year drought, droughts which are forecast to get worse with climate change? More desalination plants?

Re high immigration – “However, the evidence seems to be that, in the longer run, the average resident is better off.”

Much of that genius research is based on economic theories of little worth, proving nothing more than that ‘the average is slightly better off’ while the median is usually far worse, off, provided you assume out everything about human life that is actually meaningful because that is an externality.

I’ve read a lot of guff explaining why historically unprecedented immigration rates aren’t the reason behind dropping living standards of every measure, and all of them look at variables except for the fact that more and more people are being stuffed into places that don’t have the infrastructure to support them.

The argument then goes that this isn’t an immigration problem, it’s a planning problem, which is arse-about but true, unfortunately the planning problem is unsolvable because of politics, and the fact that we have never got that right in 200 plus years, so the answer is that high immigration actually IS the problem, and stop being stoopid.

Now if immigration rates filled in our inland and regional towns, with oodles of clever planning beforehand and no rent seeking and high taxes for windfall gains from re-purposing land, then perhaps we could do that.

But history says we can’t or won’t, which means that we can only look at the actual source of the problem – unprecedented high immigration rates for the last 20 years.

One of the rare example where the simplest solution to the problem is actually the right one. All of the suggested solutions fly in the face of reality. You could be an economist!

All the main East Coast cities are on the brink of becoming unliveable because of the population ponzi game Australian governments seem proud to play. Open-ended growth is not a sustainable concept … Australia’s eco-systems are under huge pressure through development. There are more than 300 species endangered, climate change is another pressure and the de-regulation of the labour market has sidelined low-income workers or as they are otherwise called. It’s devastating what we are doing to our people and environment in the name of the almighty dollar and globalism. When do we repay the Indigenous or do we just ignore that tyranny ad infinitum while we burn their country down?

* as they are otherwise called tge homeless

I would, of course, disagree strongly with many of this article’s conclusions, and support the comments made by JMNO and Dog’s Breakfast. However, I would like to emphasize one point. Any Pollyanna-ish piece on the supposed benefits of growth that ignores the effects of the looming crisis of climate change is worthless as a guide to the future. I expect total global societal collapse by 2100 and Australia will not be exempt. Fortunately I wont be alive to experience it.