Fats Domino, who has died aged 89, must surely be the last of the old rock’n’rollers to go. Maybe there’s a few minor players left somewhere: 90-something old upright bass players, now supine in old folks homes; saxophonists run out of breath. But Chuck, Ike, and now Fats; all the pioneers have now passed away.

With him goes a world already all but lost to our memory: an era before the amplifier and the solid-body electric guitar, when records were not cheap, and music was overwhelmingly live; when its most popular manifestations were segregated, the line seen by the powers-that-be as one dividing civilisation from something else; a period when the raucous, anarchic style known, since the 1930s, as rock’n’roll, had been developing far away from the world of radio, cinema and authorised entertainment, bubbling away for decades in juke joints and the black neighbourhoods of southern cities. A known quantity, but unspoken of, places to go, to “get some rockin”, by blacks and some whites alike, a relic of modernity, when social life was still divided between the sacred and the profane.

Antoine “Fats” Domino, born in 1928, of a Louisiana family of black and French heritage — his first language was Creole — was one of the handful of people whose career bridged that divide of the century. What has made him near-forgotten today made him fantastically popular then; he was a short, tubby, sweet-faced man, who played a form of rhythm and blues that was more driving than swing, or white country; less insistent or tearing than the rocking of Bo Diddley or Chuck Berry. They were electric guitarists, whose stage performance suggested raw sexual power; Domino was a pianist, whose music rolled more than rocked, in a way that was still plenty racy for white audiences of the era.

Born in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, where he lived until Hurricane Katrina drove him out, he left school at grade four, and worked as an iceman’s apprentice, until his uncle taught him piano. From the early ’40s onwards, aged 14, he was making a living, in juke joints — i.e. bar/brothels — nightclubs and BBQ parties, in a milieu where tens of thousands of off-duty troops supported a vast industry. He combined the rolling piano style, with a more clipped rhythm and blues. Among those gripped by that beguiling obsession — the hunt for the first true rock’n’roll song — his 1951 hit The Fat Man is often credited; it sold a million copies, at a time when black music still wasn’t being played on white stations, which had 80% of the nation’s audience. When he adapted an old lilting cowboy song Blueberry Hill, the backbeat gave it a sexual undertone, which could be simultaneously appreciated yet denied, which was the essential character of modern popular culture up to the 1990s.

In the second half of the 1950s, he had a dozen top 10 hits, his superstardom finally curtailed by the “British invasion” of 1964. Thereafter, he recorded a dozen or so albums, in a variety of semi-successful genre mixes, often unhappy country-blues mixes. One of the few ’50s stars not to be stiffed of his song rights, he stopped touring in the ’80s, and barely left New Orleans at all after 1986. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, broke and touring to the end, never lost the air of danger and excitement that came with the electric edge of their sound; a comfortable and long old age was Domino’s compensation for the fate of becoming as distant in history as bakelite and Jim Crow, polio and nylons.

A decade or so ago, it was somewhat novel to suggest that there was rock n roll before Elvis, Chuck Berry and Bill Haley; now it is commonplace to observe that the genre existed for a full decade before the mid-1950s. Ike Turner, “Big Joe” Turner, Arthur Crudup, all had, from the mid-40s onwards, been distilling and hardening the dominant rhythm and blues sound — keeping the backbeat, losing much of the swing — to create a more driving, insistent sound (hence Ike Turner’s early hit Rocket 88 about his car).

Rock’n’roll periodised the era — “before Elvis there was nothing” as John Lennon said — and also two ways of being a person. Rock’n’roll was the means by which the classical subject — with proper ego and seething unconscious, admonishing superego on top – became undone, and everything rushed into presence. In the culture, so as in the person.

The mid-century mood, from our perspective, was one of veiled desires, in the films noir of the period, in the pulps, the magazines and on the analyst’s couch. The ’60s are taken as a liberation from all that, rock’n’roll as its agency. Yet the music, with its pure desiring drive, had been present all the way through. Fats Domino, far from being a harbinger of a new style, was, even in the late 1940s, an exponent of its milder side, a safe danger for the new mainstream. His is another of those lives made extraordinary by length; a man with four years schooling, birthed on the family kitchen table, who wielded blocks of freezing, steaming ice in the morning, and played hot music all night, until it became the music of the world. This world is not as that one was, and those things only happen once, and he may have been the last to see it go.

“Fats Domino, who has died aged 89, must surely be the last of the old rock’n’rollers to go.” – That ignores the, for my money, greatest of them all, Little Richard who is still around.

I always loved Fats Domino, “Going To The River” is one of the greatest records ever made.

Sure hope he found his thrill.

‘… whose music rolled more than rocked…’

Perfect.

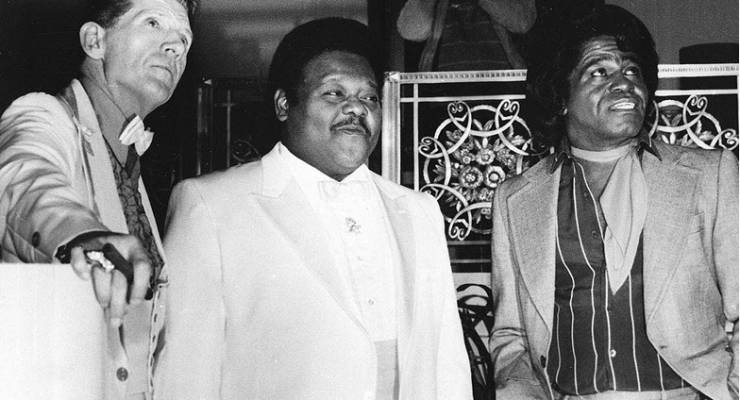

The last? Your picture has him with Killer (who is to Fats in piano skills as Trump is to Obama in integrity but who is, nevertheless, surely an “old rock’n’roller”) and he’s still with us.

Fats had a cool voice. I don’t rate the abusive Ike Turner. Chuck Berry had that great rhythm and drive, and a witty turn of phrase, Elvis had a genuinely great voice as well. Fats and Chuck also contributed a certain style to their playing. The easy swingy blues of Domino was a lovely sound. Heaven rest him well.