A publication with a name like Crikey was always going to informed by the qualities that make us “Australian”. In mainstream press, this “Australian” identity is rarely described; in fact, it often appears only as a negation: we define the national character by saying “un-Australian”; by saying, PHON-style what it is not.

We remain convinced — or, at least, hopeful — here at Crikey that “Australian” can be clarified to the point of usefulness; that it can be spoken about in a way that is not limited to old mates at the RSL or faux-larrikins dropping their pants in Malaysia. “Australian” often happens to a person within months of their migration. A suspicion of bosses, a discomfort with orthodoxies, an itch to show the middle finger while laughing.

When associate editor Bhakthi Puvanenthiran and correspondent Helen Razer learned that they had both briefly considered swearing tattooed allegiance to the Eureka Flag, Crikey decided that the time for exploration of “Australian” was now. We decided to do it by unleashing Razer on other insugrents — whatever their political hue.

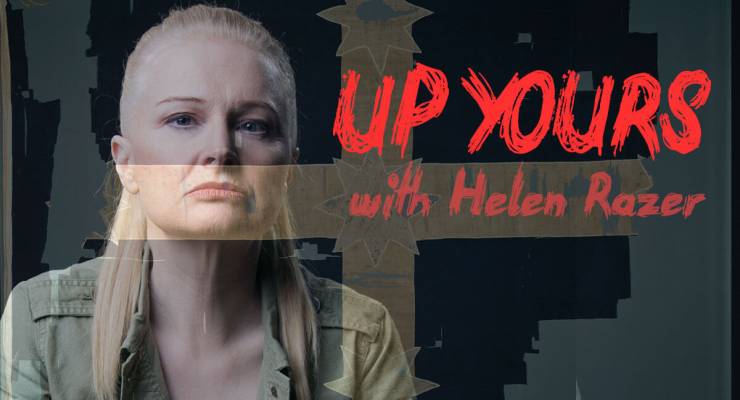

And so, Up Yours was born. Razer will continue to plead with a wide range of mouthy Australians — Tim Blair, Maxine Beneba Clarke, Assange, Latham, Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Tony Birch, Germaine, Noel, PJK — to give her the time of day. She starts with the litigable and loud publisher of New Matilda, Chris Graham. You can read his responses to Helen’s Three essential Up Yours questions here.

***

Some are born to outrage. Others have it thrust upon them. Chris Graham, a bloke of about my age, seems to achieve it very naturally every other week via Australian outlet New Matilda, of which he remains, in the face of both legal caution and Andrew Bolt’s displeasure, publisher, owner and editor-in-chief.

Chris is familiar to readers with a special interest in Aboriginal affairs, for which he has won a Walkley and several commendations. He is also known well to the nation’s defamation specialists, and certainly we in print media talk about him all the time (just last month a Crikey colleague sent me the note “Oh, Chris!” appended to Graham’s J’Accuse, which is written to the federal government and announced the guy’s refusal, budget crisis notwithstanding, to take a cent of media reform funding offered to independent news outlets).

You may not know of this bloke, both pilloried and reluctantly admired inside journalism, but it’s time you did. Because Chris, with whom I have previously enjoyed a beer — one printed with a political slogan and made by a worker-run brewery in which he has a stake — strikes me as unmistakably Australian. At least in the way that I, and, I believe, many Crikey readers would understand this range of qualities.

After years of arguing and/or agreeing with him by internet and phone, I finally met Chris, and his slab of bespoke beer, up at a Woodford eco-gathering this year. “You’re a true bastard,” I told him, after a few slugs of his “Change the Date” pilsener. “It’s true. I am, in fact, literally a bastard, being born out of wedlock. I am figuratively a bastard, as many of my critics will attest, and most of my friends.” His companion nods her head.

Later that night, well past the point of ladylike inebriation, I proposed that, “People who are born with their middle-finger raised are the true Australians, and I need to do a series on bastards like you, across the political spectrum, in Crikey”.

Chris has said, “You’re a bastard, too. And I like Crikey. Actually, it’s the model. It got in early and it changed the landscape with subscriptions, and this means you guys say important stuff to an intelligent readership, but, now, piss off. I have grog to sell.”

We took up our conversation again just as Chris was preparing reports on allegations of misconduct by Charles Waterstreet, the celebrity barrister, which have since been taken up by mainstream media.

“So, I am a hopeless optimist trapped in the mind of a political pessimist. I am unprepared to accept the reality of money, and I’ve got away with it for years.”

“I don’t pay myself, and I sold the house. I do other work. I run a news service, do ghost-writing, all sorts of media spin. The price is that I work 18 hours a day, seven days a week. The reward is New Matilda.”

New Matilda does offer a reward, particularly to readers seeking commentary on Aboriginal affairs. Amy McQuire, now at BuzzFeed, long provided meticulous accounts to NM on policy and reality past and present, and Graham is highly regarded for his work on the so-called Emergency Response. This commitment to reporting on Aboriginal affairs started one day in 2001 when Graham was working in Bateman’s Bay for Rural Press.

“A guy named Owen Carriage came into the office and said he wanted to start an Aboriginal publication.” The National Indigenous Times was launched, and Graham, then, “a white boy educated like all other white boys in [Sydney’s] Picnic Point, grew up believing there was a problem with Aboriginal people. But that it was largely the fault of drink.”

“It didn’t take long to realise my mistake. The early days of reporting in the Times were fairly anodyne, but all the while, I was led down a path that revealed deep and systematic injustice. It changed me. I suppose I could have ended up being like my old mate Joe Hildebrand, a popular contrarian.”

Instead, “My natural stubbornness was entrenched”. After a spell overseeing the now defunct Tracker, the publication of the NSW Land Council, where he worked with editor McQuire and Professor Gary Foley, he purchased New Matilda.

“I get that people think I am a fucking idiot, a terrible businessman and deeply flawed. And all of that is true. But I still get to write what I want, and I publish other people who would never be otherwise published.”

On a good day, New Matilda tells the stories of profoundly marginalised communities, often through accounts by those people. On another good day, it describes with uncomfortable accuracy the self-serving interests of mainstream Australia media. On an average day, it makes a bit of a mess, or, sometimes, publishes nothing at all.

Every day, however, “It fails to operate in the real world. And it’s glorious.”

Graham is a quixotic pessimist, an earnest cynic. A person who hopes for revolt and change, but accepts that this can only be prefigured, for the moment, in his unruly internet island.

*Read Chris Graham’s responses to Helen Razer’s Three essential Up Yours questions here

Oh Helen – journos rewriting history with comments -“People who are born with their middle-finger raised are the true Australians – Actually originally the thumb thrust upright was the true Australian sign –

With multiculturalism and European migration and American tourism – our great tradition was infiltrated and the foreign middle finger sign supplanted the indigenous sign language.

Our ab original sign language has become extinct-should we expect Parliament to cobble up a Sorry ceremony – or should we charge an entry fee at airports to resurrect our attachment too our thumb sign? Lets have a postal vote.

I cannot be certain about the object of your critique, here, Dezzer.

Thanks for popping by with it, in any case.

Helen – middle finger raised is a recent part of our sign language – the original Australian sign conveying the same meaning was the purposeful thrust of an upright thumb – this has now metamorphosed into a sign of approbation. How languages change!

I am glad you choose to use the word “approbation” correctly, though.

I have seen it used to mean “disapproval” so often, I am sure that Macquarie will just shrug soon and say, “Yeah, okay.”

(I have similarly strong feelings about “infer”. There are some words we NEED, Desmond.)

Love the series’ title. Looking forward to more, HRaz!

Thanks, JQ! You have any contacts for right bastards, send ’em my way!

Will consult my teledex under “iconoclast”!

helenATbadhostessDOTcom, baby

Mark hasn’t answered me, yet 🙁

And he’s also really fkn hot.

I will pass this on to Mr Graham, who will be delighted by your assessment, Craig!

Not only does Chris talk drivel he sells it on the side of his booze. Only a loony lefty could sell an intoxicant with a label lecturing people on the dangers of having sex without consent. Another label says Nipples are Nipples. What does that even mean?

I am certain Mr Graham will be happy to learn that you are familiar with the product that he does not produce. I believe his role is only to provide capital and promotion. It’s an all-woman brewery, and this slogan is targeted to feminists, who will understand its meaning.

I am unhappy to learn that there are persons who still believe that alcohol is the central cause of sexual assault.

I don’t think Chris identifies as a Lefty, incidentally. Anyhow. Thanks for stopping by.

NM has become an inversion of Chesterton’s apercu, “those who no longer believe in god, believe anything.”