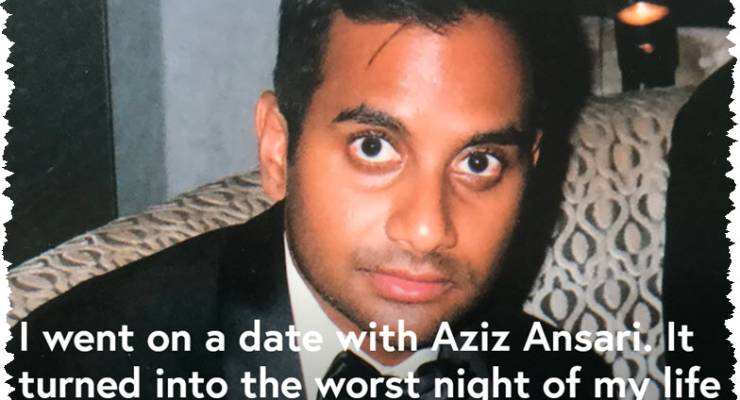

As #MeToo discourse continues to ripple out, well past the hashtag, we’re hearing a lot of discussion about a “grey area” of consent. From the viral New Yorker story Cat Person to Babe’s controversial reporting of an unnamed woman’s date with comedian/TV auteur Aziz Ansari, coerced (though not technically unlawful) sexual encounters have been thrust under the spotlight.

Vaguely described as “sexual misconduct” or “bad sex”, these experiences have many grasping for understanding. If it’s not assault, but it’s not a positive, comfortable sexual experience either, then what is it? How can we place it in the current debate, if we can’t settle on a name for it first?

“I’ve always found this a really difficult area,” says Carolyn Worth, Manager of the South Eastern Centre Against Sexual Assault. “We do get phone calls from people who have had a really bad sexual experience, and they’ll ring up and say, ‘Was I raped?’ The answer is, ‘No, you just had a bad experience’. Of course, we put it more tactfully than that.

“Bad sex isn’t rape, it’s just that: bad sex. But it’s a really tricky discussion. And it’s not our job to sit here telling people how traumatised they are. Our job is to help them get on with their life after something unpleasant has happened to them.”

Helen Campbell from the Women’s Legal Service New South Wales takes a similar stance. “There are always grey areas and potential to improve language, culture and understanding,” she told Crikey. “I think women are adults with agency and capacity to make mistakes and have regrets. [Bad sex is] not the same as being pressured into doing something we don’t want to do.”

[What Babe’s Aziz Ansari story means for the credibility of sexual assault reporting]

There’s a little more flexibility outside the world of law and crisis support, however. Deanne Carson, a sex and relationships educator and co-founder of Body Safety Australia, is passionate about what she terms “consent culture”.

“One of the first things I notice is that often the conversation turns to what is the legal definition of sexual assault and rape and consent — and often that then gets framed by ‘What can you get away with doing before you’re actually charged?’ That is just nowhere that we ever want the conversation to go,” Carson explains.

“To date we’ve been framing the conversation around, ‘What is rape? What is sexual assault? Don’t rape. No means no.’ And I think what we need to do is actually frame the conversation in a more positive light, and say what we actually want — instead of saying what we don’t want. What we actually want is a culture of consent. And that’s for every single human being, every single time, to turn up and be making sure that their interactions with other people are wanted.”

Carson has a reasonably shrewd idea as to why the culture of seeking explicit, enthusiastic consent might be backfiring on women in these “bad sex” experiences.

“Children are socialised to be compliant — and particularly girl children. So, you’ve been training girls to do all of these things to make other people happy, and then all of a sudden we expect them to go into very vulnerable personal physical situations and have a loud voice. How can that be? We’ve never taught them to do that, or we’ve never given them permission to do that. We’ve never made it safe for them to do that.”

Dr Chloé Diskin, a lecturer in Applied Linguistics at the University of Melbourne, has a similar take on the matter. She theorises that the linguistic methodology of “conversation analysis” in social interactions has a role to play.

“What seems to be happening with this whole debate around consent is we’re expecting people to be as explicit about sexual consent as they are about other things,” Diskin said, “even though in our everyday language, we don’t say things so explicitly.”

“A lot of the time when people are refusing something, it’s actually something that we inherently believe to be impolite, or what we call ‘face-threatening’. So what a lot of people do when they turn down sex is they do it indirectly. And that makes a lot of sense, because when we refuse people — refuse an invitation to a party for example — we do these kinds of things all the time.”

“I think what seems to be the problem with this whole language of consent is that we’re expecting women — in most cases — to be explicit about when they’re giving consent, which goes against all the other ways we don’t give [verbal, explicit] consent or don’t accept invitations.

“It seems like a very unnatural thing for someone to do. It’s like ‘consent equals lack of dissent’; what people interpret as giving consent is just that they haven’t said no, rather than having said yes.”

So, is there a need for refinement in the language around consent? “That kind of ‘just say no’ mentality, it’s quite ineffective because generally we don’t like to say no,” said Diskin.

As #MeToo debates rage online, it’s painfully clear there is some disconnect between all of us when it comes to what consent means, what sexual encounters are appropriate and how mutual respect in sex even works. A more nuanced understanding and application of language and communication may be a good place to start.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, domestic or family violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

I am a 74 yr old male. If I was a young man today, I would not invite a woman out, and would stick to having beer and a yarn with my footy mates. The whole business of what is appropriate behavior always is and will be personal between two individuals. It means that relationships between a man and a woman now need to be initiated and negotiated by the woman. Would women like that? Seems no other option, or maybe that is how women want it. Beers all round was that?

@Neil.

Yeah Neil I’m with you there, stick to the beer and Mates and only go out with women who come over to the bar and invite us home. We need the mates as witness if she changes her mind.

Here is a story from my past.

After a pleasant night out, I escorted my lady friend home. Being invited in for coffee my spirits started rising and I got my hopes up.

Now cutting out the details of the foregoing activities, which were mutually enjoyed, or at least no complaint was made, I moved to develop a deeper relationship.

The lady said no, I moved back to a more preparatory and persuasive attempt. This happened a number of times. On the final attempt ,I asked if she meant “Really no “. She said “really no””, I kissed her goodnight on the lips and departed.

The next few times we met she was really off me. I asked why and she replied that I had left her in the lurch, frustrated and angry.

I was floored and said “but you said NO “. She replied “a girl is supposed to say no “.

Explanations from Mat D-R, Helen R and any other women people out there would be appreciated.

I’m also developing a conspiracy theory around recent events worldwide, Is this leading up to homosexuality becoming compulsory. It must be really really difficult for young blokes today. Or bring back arranged marriages for all and cut out the mating game.

In the interests of clear communication it’s overdue for the Macquarie Dictionary to redefine & update the word ‘coffee’. Having been bandied about for decades, the secondary meaning needs to be legitimized.

It could become the 2019 Word of the Year, of more practical use than twaddle like ‘milkshake duck’.

Wasn’t it once, “come up & see my etchings”?

Sorry that trying to change a text results in submission of it: to try to complete what I wanted to say: a reflective person would recognise that a woman who utters “A girl is supposed to say no” is not candid about her feelings. Recognising that a reflective person then recognise you cannot justifiably be angry with the person you have deceived but only with yourself.

This sort of bad luck has to be expected in a world where sham standards of modesty, derived from protecting oneself from unwanted pregnancy, have no place in the modern world, where only religious beliefs can get in the way of other ways of preventing unwanted pregnancies.

There is no conspiracy behind it at all.

Strikes me you were just unlucky to meet a woman who is confused about what to do and does not have much

I’ll be glad when the dust has set on this and the new rules are spelled out – when men won’t use their position to force women to do what they don’t want : and women won’t have to flirt and act coquettish to get what they want.

Neither situation applied here.

It just seems that “NO’ in this case actually meant “hurry up and get on with it”.

BTW even back then Coffee invites on the doorstep was accepted to have a defined meaning, subject to a closer inspection, of course.

While sympathizing with the genuine cases of sexual molestation, I find it hard to believe there are thousands of females ‘out there’ who are claiming to have been assaulted, (apologies if I have used the wrong word). There appears to be an army of wrongly treated ladies. What on earth happened to the female fighting spirit? Or a swift kick in the cods? Or the squirrel grip?

So much bleating by virginal females is enough to make me throw up. (not to put too fine a point on it)

Like other areas where the notion and concept of ‘consent’ is important (like the health arena) it seems it’s only really considered deeply when something goes wrong. We’re all apparently happy to sign multi-paragraph and sometimes multi-page documents detailing what can go wrong, on the trolley outside the operating theatre, understanding little of what we read: how much more difficult to truly obtain ‘consent’ in the labyrinthine area of human relationships?

Courts are where both instances are now decided-and it’s probably equally unlikely that either party will believe they got a fair result.

It’s for this reason it’s probably good that the vast majority of consents given, in relation to sex, and surgical procedures, are the subject of trust between two people who implicitly acknowledge they know what’s going on (or what will go on).

Using the law to address a later discovered or unconvered imbalance, if that comes to pass, will solve the legal problem, but, not the human one.

Linguistic challenges aside this whole area is problematic because it is a continuum. When does rape/sexual assault turn into unreasonable pressure or into “I didn’t like that” or “he was creepy and didn’t listen”. I think the #metoo movement is a great thing, it is about time that women socialized to please stood up and said – no not good enough, no that’s wrong or yes I need to report an assault. I think the greater good will be in the empowerment of women. It will though take a bit of sorting out.

Well the suggestion here would remove uncertain signalling. I would not have initiated most of these behaviours, perhaps any of them when I was young. But I saw plenty who did and I saw plenty of women go along with it smile and encourage a good deal of what would be now called problematic. Now I was not always comfortable with the behaviour of these blokes, but the women were giggling and smiling and a bit more than that. I wonder where some of those encounters finished, In some cases I knew, but none of the women said it was assault. They might have said so and so was a fuckwit or whatever.