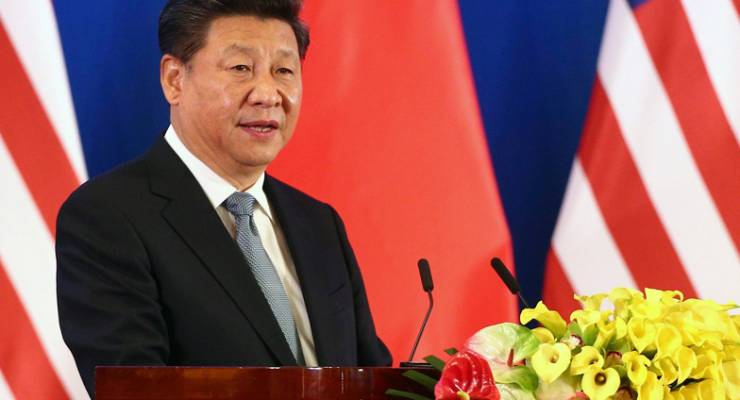

China’s recent formalisation of Xi Jinping as president for life marks the country’s turn away from partially accountable leadership to a model that is, in effect, a dictatorship. This runs counter to not only China’s post-Mao Zedong 10-year changes of leadership but also a more general global trend towards democracy.

Yet Xi is not alone, with a number of countries retaining dictatorial forms of political leadership. A dictator is understood here as a person who holds absolute political power, either formally or in a practical sense.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin has confirmed Russia’s position among their ranks. Likewise Belarus’ first and only president, Alexander Lukashenko, holds effectively absolute power in what is, in theory, a democracy. Opposition is allowed in Belarus, if vilified by the state-controlled media and restricted in running in elections. Meanwhile, the tiny number of absolute monarchies, such as the Sultan of Brunei, also hold similar powers to that of dictators.

Many “democracies” are a trope for deeply compromised political processes. And where democracy falters, as it seems now to be doing in many developed countries, ordinary people too easily turn to “strong”, charismatic leaders.

To paraphrase Brave New World author Aldous Huxley, so long as people look to Caesars and Napoleons, Caesars and Napoleons will duly rise and make them miserable.

Here’s a snapshot of how they’re currently looking in the most notable areas around the world:

Asia

In Turkmenistan, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov has ruled by personal fiat since 2007, succeeding the late president Saparmurat Niyazov who employed similar rule. In neighboring Uzbekistan, President Islam Karimov has enjoyed absolute power since 1989.

Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev has also been president since independence in 1991 and, while allowing elections, does not allow an opposition to compete in them. In Syria, the regime of President Bashar al-Assad is a de facto dictatorship, holding restricted elections in some areas in the middle of a civil war.

Closer to home, North Korea is just about everybody’s idea of a clichéd dictatorship, where the Kim dynasty has ruled the country unimpeded since 1948.

Further south, Cambodia is now effectively a dictatorship, with Hun Sen Prime Minister since 1985, banning all viable opposition and saying he intends to stay as leader for another two decades. Next door in Laos, President Bounnhang Vorachith is both head of state and de facto leader, but shares power with a small central committee headed by a prime minister. So, while Laos is a closed authoritarian one party state, as is Vietnam, they are not technically dictatorships.

Thailand has had a dictatorship since the military coup of 2014 in which General Prayuth Chan-ocha installed himself as prime minister. Under Thailand’s new restricted constitution, new elections (when they are eventually held) may see him continue in power.

Africa

Africa has historically been a hotbed of dictatorship, although it’s currently enjoying an uplift in democratic transitions. Even so, Algeria, Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Rwanda and Sudan are all either dictatorships or very close to complying with that term.

So too in Equatorial Guinea where President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has been in power since 1979, when he overthrew his own uncle. In Zimbabwe, Emmerson Mnangagwa succeeded Robert Mugabe as an all-powerful ruler.

The Americas

Juntas may be dictatorial in style but are actually small, tightly controlled committees, as are politburos (central committees). Latin America popularized the term junta and has had a colorful parade of dictators, but has been reduced from its dictatorial heights of the 1970s to just one: President Raoul Castro of Cuba.

Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia’s and Nicaragua all have elections, even if doubts have been expressed about some of their electoral systems, with Venezuela being the most compromised.

Damien Kingsbury is Deakin University’s Professor of International Politics.

What limits the power of our own Head of State, Queen Liz? She’s been up there since 1953, following on from her father. It would seem that only a few strokes of a pen/quill would put her in full charge of the joint. That’s if she could be bothered to do so and the people thought it would be an improvement. Perhaps the power stays with our lower Houses only while their governance continues to show a certain minimum of competence.

The constitution has limited the monarch’s power in the UK and Australia since the 19th century.

“China’s recent formalisation of Xi Jinping as president for life marks the country’s turn away from partially accountable leadership to a model that is, in effect, a dictatorship”

He has not been formalised as “president for life”; the term limits that formerly applied have been eliminated. Whether that is a good thing or not, your statement is wrong and should be corrected. Also, I do not see any change in the leadership’s accountability as a result of this change. As you point out, that accountability was always limited (in effect to the senior members of the CCP) and it continues as before. Anyone who has followed the factional politics that has played out in that party would agree that there is plenty of accountability within it, if not to the nation as a whole. Xi has certainly consolidated his power, and eliminated many of his factional enemies. That is quite different to the term limit question which I believe was supported to overcome the “lame duck” issue with the former practice of effectively anointing the new leadership team in the second Presidential term, resulting in the recalcitrant anti-reformers simply “waiting out” the expiry of the term. They will not be able to reliably do this now.

Agreed. Isn’t a much more interesting question, seeing the government exists for party purposes, why does the party think this is more important now?’

Deng made the leadership changes not ONLY to avoid the failures and excess of Mao’s China, but to break the social and economic ‘iron rice bowl’ to create a more dynamic, competitive, etc national economy and government. A large part of that was decentralised power. Now that those objectives have largely been achieved, or in place, what are the new challenges? I think the plain and obvious answer is all kinds of security threats. The move to a more centralised leadership is logical. Environment enforcement, economic risk, anti-corruption drives, have all been failures ik

Roger, your comment adds naught to the serious threats Professor Kingsbury draws to our attention. Today, across the globe real politic requires even the strongest democratic states to associate with dictatorships and authoritarian leaderships that bastardize rule of law, oppress and repress their peoples. To found a democracy generally follows extreme bloodshed; and to maintain a democracy requires eternal vigilance as those that are handed power, left unscrutinized inevitably fall, become corrupt.

Australia, for all our faults until most recent times, held strongly to democratic values. But today, even the most disengaged know; our nation has weakened. Equity, fair go, transparency and accountability means far less to our political class, corporates and . . . god help us, banks . . . than was the case of more vigilant previous generations? In a very short period of our national history Australia drifts . . .

Graybul – yes, perhaps I should not have made light of the article’s concerns. However the absence of democracy does not imply that power is unbridled. With much more authority than I could muster, DCParker above has sketched accountability in modern high China. CP FitzGerald wrote a book showing that in the then-new communist China, the venerable Taoist power balance of three communities – peasantry, monks and mandarins – had survived the turmoil of revolution.