Sacred Cows is a new series dedicated to overrated cultural artefacts and the more deserving ones we’ve lost sight of in their shadows. Each installment will pose an argument for one or the other, re-evaluating the worth of a text and the praise it has (or hasn’t) received.

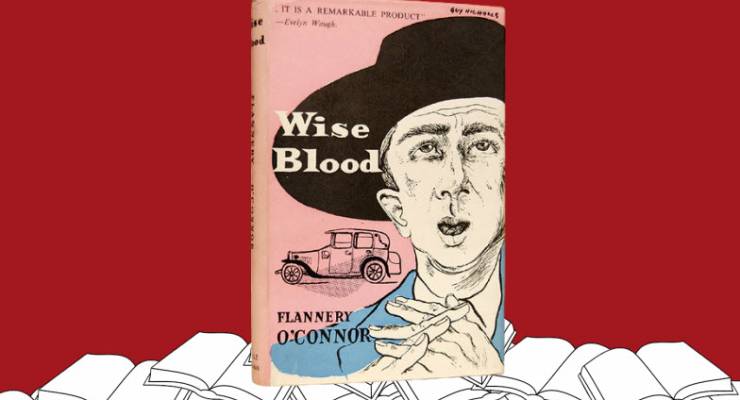

This week, David Latham makes the case for Flannery O’Connor’s 1952 novel Wise Blood.

Some writers are born out of time. When Flannery O’Connor published her first book, the fantastic Southern Gothic novel, Wise Blood, the culture and literature of 1950s America was starting to bend toward a more interrogatory exploration of the American South, while in the North a sort of muscular high-mindedness began to assert itself as the gleaming post-war sheen started to corrode. That has meant that O’Connor did not enjoy the popularity and acclaim of fellow Southern Gothic writers like Cormac McCarthy, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote or William Faulkner — the last of which I believe she surpasses as a writer.

Not since Joseph de Maistre has such a dark, Hobbesian vision of the world been articulated in written form. O’Connor was a Catholic writer whose Catholicism was brutal, and the stage on which her characters walk was that of an already fallen world. Acts won’t save anyone, only grace, but God’s good grace is in such short supply in O’Connor’s South it never manages to manifest itself.

Wise Blood follows the journey of the intense and unusual Hazel “Haze” Motes who, after returning home after World War II, makes his way from the dust-covered and now abandoned town of Eastrod to the fictional southern city of Taulkinham, where he intends to win adherents to his new church, The Church Without Christ.

After arriving by train, Haze meets an assortment of eccentrics: 18-year-old Enoch Emery who works at the zoo, watches women at the local pool from a bush and detects haughty attitudes in animals; father and daughter fake evangelists, Asa and Sabbath Hawks; and another Jesus panhandler, Hoover Shoats, who tries to monetise Haze’s new church venture.

Haze is a self-contained, insistent and rather deluded young man, but in the context of the novel he doesn’t stand out as uniquely strange, which is a testament to O’Connor’s ability to fashion a world where Southern protestant evangelism forms a sort of amusement park backdrop.

O’Connor is a master of a sort of glib grotesquery that doesn’t edify itself for the reader. In one scene, when Sabbath Hawks is preaching to Haze about Jesus’ redemptive powers, she segues into a story about infanticide:

This here man and woman killed this little baby. It was her own child but it was ugly and she never give it any love. This child had Jesus and this woman didn’t have nothing but good looks and a man she was living in sin with. She sent the child away and it come back and she sent it away again and ever’ time she sent it away it come back to where her and this man was living in sin. They strangled it with a silk stocking and hung it in the chimney. It didn’t give her any peace after that, though. Everything she looked at was that child. Jesus made it beautiful to haunt her.

Told in a close third person perspective, there is no mawkishness or lesson peddling from the narrator, and none from the characters. There’s no self-conscious reflexivity, no moments where the characters critically question their motives and undergo some revelatory vault face to accommodate predominating social mores or values existing outside of the book, which is refreshing in an age where those lines are getting obliterated in art.

The bluntness of O’Connor’s storytelling combined with arresting imagery and a superb vernacular style also make Wise Blood an extremely funny book on occasions.

One such scene involves Enoch whose “wise blood” tells him that Haze is about to deliver a moment full of import for Enoch and the world. Travelling across town with a shrunken “Jesus” (an exhibit he stole from a museum), Haze’s pending eschatological miracle proves insufficient to prevent Enoch from making a brief detour. Enoch stops outside a cinema where he lines up to meet a famous gorilla known as “Gonga”. For Enoch “an opportunity to insult a successful ape came from the hand of Providence”. But after lining up and trying to think of a clever insult, he ends up delivering the bumbling message of a supplicant, only to discover the ape is actually a surly man in a suit who tells him “you go to hell”.

O’Connor’s bleak and darkly comic Catholic vision is probably best exemplified in the unremitting short story A Good Man is Hard to Find, but Wise Blood is an underrated classic of Southern Gothic literature and a fantastic debut novel. O’Connor’s oeuvre, while small, should rightfully have propelled her over other popular and critically acclaimed writers of the genre.

I’ve recently whinged about filler … err, filling Crikey.

This was a fine piece of reading.

Well written, enthralling & intriguing.

BTW, I also abjure & withdraw my earlier comments about the recent tek-glitch with the submit button, apparently on all formats.

In the past, many commenters have rued Crikey not having an “edit” option when a typo, or some unfortunate infelicitude, have slipped into ones otherwise magnificently lucid, world enlightening compositions.

It is extremely handy, not to say “so embarrassment” saving, in this modern daze of dashing off apercus before a champagne breakfast but, nyah, serves us right.

However, I have found since this tweek was introduced that it has saved me several too many opportunities to correct a slab of verbiage.

So, well done. OK? Sorry.

And, thanks again for this erudite review of an author of whom I was unaware – my local library has her short stories and a DVD of John Huston’s adaptation.