Sacred Cows is a series dedicated to overrated cultural artefacts and the more deserving ones we’ve lost sight of in their shadows. Each installment will pose an argument for one or the other, re-evaluating the worth of a text and the praise it has (or hasn’t) received.

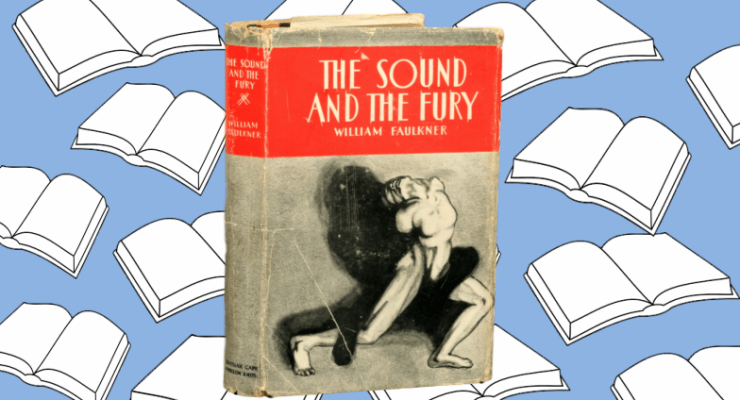

This week, David Latham makes the case against William Faulkner’s 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury.

As in life, so too in literary criticism there exists a troubling tendency amongst humans to transform flaws into virtues.

That William Faulkner’s abstruse The Sound and the Fury has been elevated onto a literary golden mesa and is now bowed down before as a literary totem is an exemplar of this sad condition, and one of the universe’s great and terrible mysteries.

Written in a wilfully opaque, Byzantine, multi-perspectival mode, The Sound and the Fury does no favours to the reader and violence to the book which already contains some of literature’s most unlikeable and impenetrable characters. It’s a turgid book whose very impenetrability seems to account for half its cultural cache (see also Ulysses and Gravity’s Rainbow).

This monstrous book is written in four chapters: three of them cover three consecutive April days in 1928, the fourth a June day in 1910. The novel seeks to reveal the machinations of a down at heel former southern American aristocratic family known as the Compsons whose fortunes have been unravelling for some time (not that you’d be able to discern this from the words you encounter). We only know about this ancestral denouement because of the generous efforts of literary scholars to construct meaning from this ludicrous jumble of words, and because in 1945 Faulkner provided an appendix of the Compson family history (1699-1945) before the story was published in a forthcoming anthology.

If you happened to be one of the poor specimens who attempted to read this book before in its naked, hieroglyphic splendour, you would struggle, I suggest, to divine anything this family’s long decline, nor anything tragic about it.

The whirlwind opening of the book offers a melange of convoluted thoughts, memories and voices — the emanations of which the reader is not informed — but which we slowly learn through painstaking reading emanates from the point of view of a 33-year-old narrator named Benjy who has some type of intellectual disability. We are introduced to an avalanche of characters in the first dozen pages, none of whose relationships are made clear to the reader through the disjointed first person narrative which also fails to delineate any traits that might help the reader to distinguish each character. Also, helpfully, Benjy’s name changes during the course of the chapter without any clear markers, while we also get unclear temporal shifts between the present, his teenage years and his infancy.

Stream of consciousness is a risky form and, admittedly can produce diabolical works like Will Self’s Shark, but there are also works like Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment or Kerouac’s On the Road which suggest it’s a shaft that can be mined successfully. The singularity of perspective in those books, of Raskolnikov and Sal Paradise, helps immensely. By contrast in The Sound and the Fury there not only exist four perspectives — three from different family members while the last chapter introduces a third person omniscient narrator — but the novel is simply crowded out with too many characters we can’t be expected to know and whose sympathies the author doesn’t elicit much interest in.

Dumping an avalanche of information on the reader through clipped first person narrators does not provide any insight into each character nor the story, and comes off as a very laboured avant-garde gesture. For all the energy expended, very little happens in the novel that can bear any real emotional weight.

Not every book needs a singular protagonist but it should at least have a line of narrative development rather than a clutch of episodic events. Faulkner’s book is a love affair with form and modernism, where the collateral damage is the reader.

Playing with form was very a la mode in the 1920s and 1930s. Ezra Pound’s exhortation to “make it new” summarised the attitude of the modernist outlook on the traditional novel. This energetic brio produced some fantastic literature like Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood, but in regard to The Sound and the Fury, this noble experiment failed the first principle of a book: readability.

Ultimately, reading The Sound and the Fury is what it feels like when someone subtly smashes their ambition over your head, which is probably why it evaded critical acclaim on its publication in 1929.

I have tried so many times to read “Ulysses ” – because literature – and so many times have I failed. Sometimes authors delve too deeply into an experiment and can’t find their way out again.

But, what do I know?

Have not read this book but note that Virginia Woolf successfully used stream of consciousness techniques in To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway. Not obscure rubbish at all.

I liked it

The Quentin monologue is one of the best things I’ve every read. Love this book.