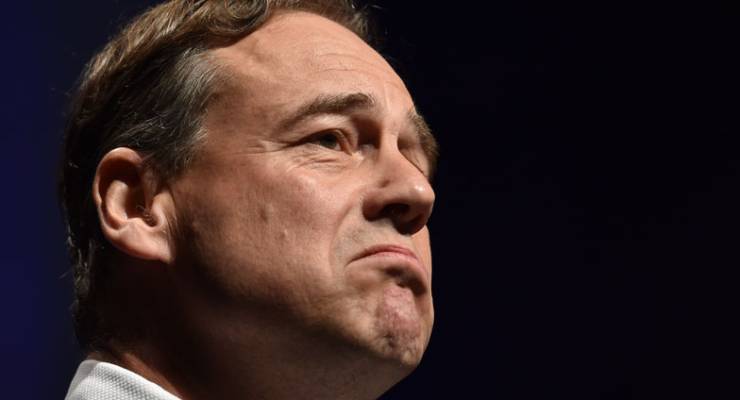

The Parliamentary Library has humiliated Health Minister Greg Hunt, with a new paper from the independent body within parliament demolishing his claim that health records created under the My Health Record system can’t be obtained by police and other agencies without a “court order”.

Hunt and his office have been adamant that no health records would be handed over to police, the Tax Office, Centrelink or any other government body in the absence of a judicial order, despite s.70 of the My Health Records Act being crystal clear that there is no such requirement. “No documents will be released without a court order,” Hunt told News Corp’s Sue Dunlevy.

Hunt was either lying or has been misled by his staff and the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA), which has presided over the My Health Record debacle. The Parliamentary Library, which independently produces information papers on issues or legislation before Parliament, was clear in a paper released on Monday (hat tip to Guardian’s Paul Karp for spotting it):

Although it has been reported that the ADHA’s ‘operating policy is to release information only where the request is subject to judicial oversight’, the My Health Records Act 2012 does not mandate this and it does not appear that the ADHA’s operating policy is supported by any rule or regulation. As legislation would normally take precedence over an agency’s ‘operating policy’, this means that unless the ADHA has deemed a request unreasonable, it cannot routinely require a law enforcement body to get a warrant, and its operating policy can be ignored or changed at any time. The Health Minister’s assertions that no one’s data can be used to ‘criminalise’ them and that ‘the Digital Health Agency has again reaffirmed today that material … can only be accessed with a court order’ seem at odds with the legislation which only requires a reasonable belief that disclosure of a person’s data is reasonably necessary to prevent, detect, investigate or prosecute a criminal offence.

How Hunt allowed himself to be misled on such a simple issue isn’t clear — he is a former lawyer, and while he has been in politics for 20 years, surely that hasn’t extinguished his ability to read basic legislation. Even this morning at a media conference, Hunt was persisting in the fiction that the records couldn’t be released in the absence of judicial direction, suggesting it isn’t merely a mistake on his part or poor advice from bureaucrats.

The library also points out that the legislation is a major weakening of existing protections around health records:

… it represents a significant reduction in the legal threshold for the release of private medical information to law enforcement. Currently, unless a patient consents to the release of their medical records, or disclosure is required to meet a doctor’s mandatory reporting obligations (e.g. in cases of suspected child sexual abuse), law enforcement agencies can only access a person’s records (via their doctor) with a warrant, subpoena or court order.

It also raises further questions about the government’s (mis)communication strategy around My Health Record, which has involved:

- making the system opt-out but running no widespread information campaign beyond flyers in post offices and doctors’ surgeries;

- Hunt and his office pressuring key stakeholders to retract critical comments;

- the ADHA personally attacking journalists for accurately reporting on the debacle; and

- repeatedly and falsely claiming records could not be handed over.

In other words, the strategy is to hope people don’t know a health record is being created for them, then mislead and attack when the media point out major flaws in the system.

Inexplicably, Hunt has declined an opportunity to blame Labor for the mess. The My Health Record legislation was passed by Labor in 2012 and it was Labor that, as the Parliamentary Library puts it, introduced this “significant reduction in the legal threshold”. The smart political play would have been to say it was Labor’s and the government would move to restore the threshold. It would also have been appropriate payback, given Labor has been happy to snipe from the sidelines on this debacle without making any real effort to stand up for the privacy of Australians. Instead, it is Hunt that is now discredited.

Clearly Hunt & his LNP colleagues have become altogether too cocky when a warranted opportunity to blame Labor has not been seized.

Your headline assumes that Hunt had some credibility. I beg to differ.

Good one dog’s, exactly what immediately come to my mind, but mine had some colourful expletives interspersed.

Hunt had credibility? When did this happen?!?!?

Lie, cheat and steal our info and expect us to trust this government and myhealth.

What a bloody joke

Melanie, if you were involved in an accident and your health records were pertinent to saving your life would be dismissive of the program?

Only asking, as I share your concerns about the diminution of privacy , though perhaps cynically I doubt that we have any privacy today.

i dont want my meical records up for sale, which i believe this government will do

No, i dont trust the government to not allow say employers to access medical records, i dont need to be discriminated against for mental health problems

Id rather the program be opt in. The possible what if regarding an accident is less risk than the lack of security the government has for myhealth

I simply do not trust the government to run this when they couldnt even run a census

How do you shatter a bubble?

“Lying or misled by his staff” ….Hmmm?

And maybe it was just another “Children Overboard Non-core Promise”?

KLEWSO You blow on it.