Over the past month, Australia has lost a prime minister and the ABC has lost its chair and managing director. You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to know that one media organisation — led by one media mogul — was instrumental in fuelling and encouraging that turmoil. Today we continue a series looking at the shadow of fear that hovers permanently over Australian democracy.

In 1995, I spent several months reporting for a profile of [Rupert] Murdoch for The New Yorker. During ten days in his offices, I attended meetings, witnessed negotiations, listened to his phone calls, and conducted about twenty hours of taped interviews with him. At least a couple of times each day, he talked on the phone with an editor in order to suggest a story based on something that he’d heard. This prompted me to ask, “Of all the things in your business empire, what gives you the most pleasure?”

‘Being involved with the editor of a paper in a day-to-day campaign,’ he answered instantly. ‘Trying to influence people.’

Ken Auletta, The New Yorker, 2007

Malcolm has got to go.

Murdoch, meeting with Seven West owner Kerry Stokes, August 2018

Rupert Murdoch, and those who work for him, have an oddly coy relationship with his influence over influential people, and what he extracts when using that influence. When former News Corp Australia boss John Hartigan denied there was any directive from Murdoch to advocate for “regime change” of the Julia Gillard-led Labor government, it came with a monumental caveat that no such directive was needed, as “we think as a company”. Murdoch insisted in front of the Leveson inquiry: “I’ve never asked a prime minister for anything … We have never pushed our commercial interests in our papers.”

Yet, in Australia and elsewhere, prime minister after prime minister after prime minister seek out his company. Laws, coincidentally or not, do move in ways that favour his interests. And of course, it still makes no difference if he changes allegiances.

Whatever role he played in the toppling of Malcolm Turnbull, it is far from the first time for Murdoch; in every era and every country he has attempted to not merely report the news, but bring it about.

Gough Whitlam

Murdoch was initially an enthusiastic supporter of the Whitlam program, going so far as to donate $75,000 in cash and free advertising to Whitlam’s “It’s Time” campaign, frequently contacting Labor tacticians Mick Young and Eric Walsh and making suggestions (many of which were adopted). Murdoch even went so far as to draft a speech on Whitlam’s behalf (a few lines ended up getting used). Within three years, Murdoch campaigned with equal commitment to have Whitlam turfed from office. Canberra veteran and Crikey alum Mungo MacCallum called it “the most extraordinarily ruthless and one-sided political coverage any of us can remember”.

This wasn’t merely the view of Murdoch’s traditional enemies, or Labor sympathisers. In October 1975, 76 members of The Australian went on the first strike over a paper’s editorial stance in Australian history, citing the “blind, biased, tunnel-visioned, ad hoc, logically confused and relentless” coverage of the Whitlam government. “We cannot be loyal to a propaganda sheet”.

Murdoch refused to make a single concession, and there was an exodus of staff over the following months.

Margaret Thatcher

“We’ve got to get her out of this jam somehow,” Murdoch said to his News of the World columnist Woodrow Wyatt on January 14, 1986. Margaret Thatcher was engulfed in the Westland affair — a public spat with her own cabinet over the fate of Britain’s last helicopter manufacturer — beset by damaging leaks, public disunity and ministerial resignations. It got to the point that Thatcher herself admitted; “by six o’clock this evening, I may no longer be prime minister”.

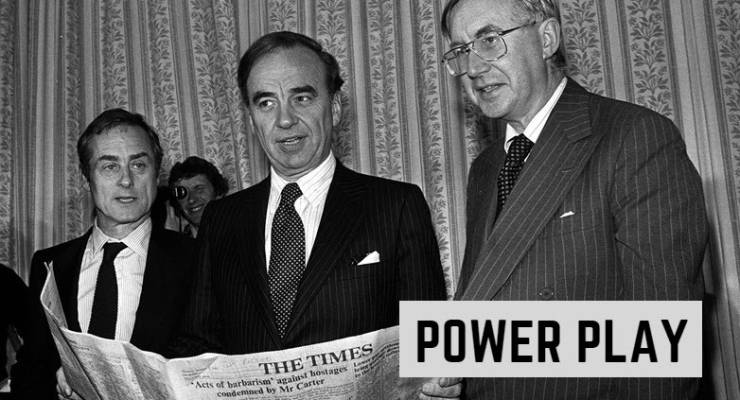

Murdoch perhaps owed Thatcher. Her government had, after personal lobbying from the tycoon, waved through his acquisition of The Times in 1981, which they could have blocked by referring the bid to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (Murdoch already owned the Sun and the News of the World). He had also benefited from Thatcher’s union-smashing when News faced a lengthy (and ultimately unsuccessful) strike at it’s Wapping plant.

Regardless, the Times and the Sun came to her aid; publishing several stories discrediting her rival Michael Heseltine, while inconsistencies in Thatcher’s story were left unexamined. Murdoch even considered personally intervening in the business deal for Westland to save her. Eventually her trade and industry secretary, Leon Brittan, took the fall on her behalf, and Thatcher stayed on as leader for a further six years.

Kevin Rudd

Kevin Rudd cannot pass a reflective surface without telling it how poorly he was treated by everyone he’s ever had anything to do with, and did plenty to ensure Labor was unelectable in 2013 without anyone helping. Plus, he’s got a new book out. So when Rudd calls Murdoch a “cancer at the heart of Australia democracy” — this being the man he assiduously courted in opposition, and who helped Rudd regain the Labor leadership with relentless attacks on Julia Gillard — it ought to be consumed with about as much salt as a margarita. However the following front pages across the Murdoch tabloids (all within five days leading up to the 2013 election) tell their own story:

And the editors of the papers in question could scarcely argue they were unaware of their proprietor’s preference.

“Kevin Rudd cannot pass a reflective surface without telling it how poorly he was treated by everyone he’s ever had anything to do with, … ” Great line Charlie – best I have read for ages.

Not bad but a little derivative. To my knowledge, the original was a reference to Winston Peters made by David Lange when Peters was running late for an appointment with a large delegation.

Lange apologised for Peters, explaining that Peters ” had probably been waylaid by a full length mirror”.

Carole King put it to music “..one eye on the mirror and you watched yourself go by”.

Krudd needed no konspiracy against him to be unelectable – like la Klingon, the more exposure the less they were liked.

… oops, Carly Simon.

I don’t follow Twitter, but Rupie hasn’t been contributing lately has he?

If Labor should fall over the line into office and its first actions are not the cessation of all advertising in the mudorc’s meeja and a major ATO audit then they will be lucky to last even 3 years.

Nice to have a succinct report Charlie but is it something that we did not already know – or at least harbour suspicions or suppositions ? Secondly, is there a media organisaton (including Crikey) that does’t play by the same rules nowadays; adjectives instead of facts. Would you have me supply some topics of late ?