How does Australia top a year where the Monash Forum, Adani, and “soil magic” won again?

Gaze into Crikey’s solar-powered crystal ball and see what 2020 has in store for energy news!

Australia loses its last federal renewables policy

2020 will officially mark the completion of a primary mechanism for renewable growth over the past decade — the first Rudd government’s 20%, large-scale Renewable Energy Target (RET).

Technically, Australia already hit our 33,000 giggawatt hour (GWh) target — slashed from 45,000GWh by Tony Abbott after he failed to kill it entirely — with a Tasmanian wind farm approved in August.

So six years since the carbon price was replaced with “nothing”, Australia will enter 2020 with no targeted renewables policy, leaving just the Gillard era’s investment bodies — the large-scale Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and innovation-focused Australian Renewable Energy Agency — as active drivers at the federal level. Their priorities will also evolve, largely in terms of new technologies, grid requirements, and investment ecosystem.

But in the face of the RET’s likely completion and that ongoing policy vacuum, investment continues to dip after an early 2018 peak. With Angus Taylor refusing an extension and even the aggressively-useless NEG still dead in the water, that slowdown is likely to continue into 2020.

“Emissions aren’t rising as fast as they would be because the RET is doing its thing for its last year of growth,” says Ketan Joshi, an Oslo-based climate communicator. “In 2020, the government will keep taking credit for the Labor party’s policy — even though it desperately tried to scrap it. In 2021, 22, 23, they won’t be able to do this.”

Pumped-hydro, hydrogen, and other hodge-podge ‘firming’ plans

While the Morrison government’s central climate policy, the $2 billion “soil magic” fund, is effectively a repackaged Abbott-era fig leaf, the party actually does have a few energy-related plans. Some even tangentially relate to decarbonisation, although many go the exact opposite way.

Come December 31, Angus Taylor’s pet underwriting scheme is expected to have approved up to six of its 12 shortlisted projects: six pumped-hydro projects — which store energy from renewables by pumping water up and down hills — five gas projects, and one small coal-fired power plant owned by a coal baron and Coalition donor Trevor St Baker.

There’s the Coalition’s retail price caps and yet-to-be-passed “forced divestment” legislation, an ad-hoc, interventionist package that’s been slammed by Grattan Institute for blocking more crucial investment.

The Coalition also supports two long-term pumped-hydro projects: Snowy Hydro 2.0, which, subject to NSW environmental approval, will commence main works in 2020; and Tasmania’s “Battery of the Nation” (BOTN) and Marinus Link to Victoria, which has entered public consultation. Both will (only) become useful if Australia ramps up renewable generation.

Finally, the National Hydrogen Strategy — agreed to by the federal and state governments last month at COAG — will see the CEFC and ARENA inject a combined $370 million to kickstart the very early stage industry.

But COAG also rejected a Greens-led push to limit funds to “clean hydrogen” sourced from renewables, meaning that there’s the very real likelihood of the Coalition positioning hydrogen as a Trojan horse for fossil fuels.

See also: the resurgence of the expensive, inefficient carbon capture and storage thought bubble.

State action

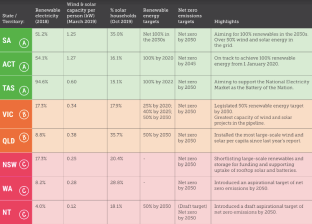

Holding the fort, and likely the only hope for decarbonising Australia over the next three years, are the state and territory governments.

The golden child, South Australia, sits at just over 50% renewables with a slate of new projects set to enter the grid next year — including a 50% expansion of its Tesla battery, co-funded, hilariously, by a federal government that once mocked it as a publicity stunt.

The ACT has technically just hit its 2020 target of 100% “sourced” renewables, while Tasmania, currently at about 95%, will continue work on the BOTN which, as early as 2027, could see that number jump to 200% and beyond.

Victoria should hit its own RET of 25% next year, while Queensland will keep jumping between legitimate progress and several new coal mines in the Carmichael region — expect plenty of fights over the Adani mine, which has only technically begun preliminary works.

For the dud states, smart money says NSW Energy Minister Matt Kean finally pulls NSW out of neutral.

Even the two worst performers will see updates on export projects: the Northern Territory’s $20 billion Sun Cable solar energy link to Singapore, and Western Australia’s massive solar-wind-hydrogen Asia Renewable Energy Hub. WA will also release a new climate policy next year.

Finally, 2020 gives voters in Queensland, the Northern Territory, and the ACT a chance to push all parties on climate action. Don’t fuck it up, voters!

Growing pains

The combination of new renewables, ageing coal plants, climate emergency-exacerbated weather extremes and a complete lack of federal planning means Australia’s grid is sure to make plenty of headlines next year.

“Despite the high probability of big improvements in storage, the stuff that replaces old fossil fuels needs strong, certain and clear planning, climate and energy policy for deployment to work well,” Joshi told Crikey. “None of that is being delivered by the government, and so what we’ll see in 2020 energy news is the consequences of a lack of planning, such as [blackouts], blamed on renewables.”

For guidance, we have the Australian Energy Market Operator’s 2018 Integrated Systems Plan — a two-decade infrastructure forecast that’s due for an update next year — although AEMO predicts that marginal loss factors will only increase as generation outstrips transmission infrastructure.

As Joshi notes, there are evolving controversies of who should pay for the changing grid requirements: the generator, retailer, customer, state and/or federal government. The Coalition, to its credit, addressed the funding problem in part in October with a $1 billion investment for the CEFC’s Grid Reliability Fund.

Finally, an upside to this stage of the transition, according to Joshi, is that for Australia “a very significant change will be the ‘shape’ of new facilities — co-located wind, solar and storage that is competitive with existing fossil fuel plants, but better because it is newer, more stable, more flexible and more responsive”.

What is the state of play at Adani? Have they actually dug a hole yet? I see nothing about it in the media. Has it employed anybody much?

I live in South Australia, and would just like to point out that our State’s ‘golden child’ status you mention was ALL done by Jay Wetherill’s LABOR government.

This mob of useless efwits who are now in government here are trying very hard to take all the credit, but anyone with more than half a brain knows they have done about as much as their Federal fellow travelers about this issue…NOTHING!!

It is indeed a wicked problem; for all of us, not just the Coalition government. I believe three things hold us back.

Firstly, the fact that energy and climate policy at the federal level is captive to the fossil fuel industry (and to a slightly lesser extent monopoly agribusiness), means that to move forward on policy the coalition parties would have wean themselves off the carbon teat. For the LNP this would amount to financial suicide unless other deep pockets were prepared to offer more attractive inducement. I guess this isn’t impossible; conceivably the interests in the FIRE sector might be prepared to put the money on the table – especially given the loss horizon stretching out before them.

Secondly, the LNP have won three elections on the trot largely by persuading sufficient voters that global incineration isn’t happening, or if it is it won’t be bad, or if it is bad there’s nothing we can do about it anyway. To move forward on policy would mean abandoning their most effective political weapon. Consider some of the outrageous lies they propagated at the last election about utes and weekends and the devastating cost to the budget of climate change action. To move forward on policy now would be political suicide.

Thirdly, there is the personal. To quote Upton Sinclair, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Individually, the Coalition members, Morrison down are caught in the liar’s trap. At this historical point, the denialist magazine is empty. Even the thickest of MPs (and I sense that’s a long roll call) can no longer seriously believe the bullshit. To maintain their position therefore, they must internalise a kind of personal denial much of which is now based on looking away. The longer you persist in a lie, the harder it is to admit the truth. To walk back from that at this point would be an admission that they are a bunch of shameless liars, at worst, or incompetent nincompoops at best. (Personally I go with the combination of both, but that’s another matter). Even the spinologists of the murdochracy would struggle to square that particular circle.

It is an audacious conceit to assert that providing backup power for an intermittent renewable generator is someone else’s responsibility. It is also politically unwise. A change of government could easily flick the noisy parasites off the grid. Instead it is the responsibility of a renewables generator to provide firming power so that they offer the grid electricity on demand. Without such responsible planning, the renewables operators risk causing statewide blackouts, which surely must be blamed on themselves.

So Roger,

is it an audacious conceit to assert that providing backup power for any generator at all (they ALL have downtime both expected and not) is someone else’s responsibility?

When coal generators go down (common in heatwaves), the operators risk causing statewide blackouts. Surely that must be blamed on themselves. At least they aren’t emitting large amounts of pollution when they are down.