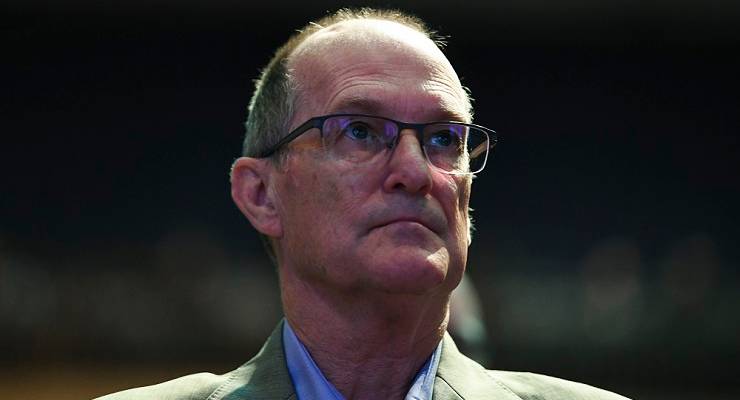

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet secretary Phil Gaetjens’ attempt to protect the government from the sports rorts scandal bears all the characteristics of the longtime political staffer he is, not the public servant he is paid to be.

Instead of providing the report he prepared on whether Bridget McKenzie’s “administration” of the community sports infrastructure grants program breached the Statement of Ministerial Standards, Gaetjens last week chose to give the Senate committee investigating the scandal a letter explaining how he’d reached his conclusions.

Those conclusions were exactly what the government needed — that overall the program had not been rorted, but that McKenzie had failed a trivial admin requirement of declaring a small gift, so she had to go. There was no conspiracy here, just a lone gunwoman.

The ensuing reaction has damaged Gaetjens’ reputation — especially the criticism from one of his predecessors, Mike Keating.

Gaetjens’ letter does explain something that Scott Morrison failed to mention when giving his verbal account of Gaetjens’ report — that “there were some significant shortcomings with respect to the Minister’s decision making role”, mainly around transparency.

And he says the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs) should be extended to entities like the Sports Commission, which are currently exempt. Which is a funny coincidence, because that’s what the government, in the wake of the scandal, has been forced to do.

Otherwise, Gaetjens gives a tick to the program, declaring “I did not find evidence that the separate funding approval process conducted in the Minister’s office was unduly influenced by reference to ‘marginal’ or ‘targeted’ electorates.”

Instead, he tries to explain away various problems identified by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report, using distraction, selectivity and straw man arguments. Exactly what you’d expect from a long-time political staffer.

First, Gaetjens wants us to know that McKenzie had enormous discretion about how she administered the grants.

Except, as the audit reveals, there is no evidence of how or even if those “other factors” were used at all. McKenzie’s staff admitted — under compulsion — to the ANAO that “there were no records available that explained how they had individually or collectively impacted upon the decision-making process”.

And of course McKenzie had no power to be the final approver. Only the Sports Commission, under its act, could approve the funds. As the audit makes clear, the legal basis on which she approved funding isn’t clear.

Remember, Gaetjens’ job was to find out if McKenzie had breached the Statement of Ministerial Standards, which centre around integrity, fairness and accountability.

McKenzie avoided the requirements of the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines when she (or was it the PMO?) picked the Sports Commission to run the program, ignoring at least two existing programs, one run by the Department of Health and another by the Department of Infrastructure — which are subject to the CGGs — that provided sports infrastructure grants.

McKenzie’s handling of the program would have repeatedly breached the CGGs, which is why Gaetjens ends up agreeing there should be no more exemptions to them.

Where was the integrity, fairness and accountability of deliberately picking an agency that was exempt from the CGGs to replicate programs already being delivered elsewhere?

Gaetjens then deploys a straw man argument to “prove” that electoral machinations involving marginal or targeted seats did not feature in McKenzie’s decisions.

McKenzie didn’t see the spreadsheet listing grant applications against marginal/targeted electorates, so she couldn’t have rorted the grants!

This appears to be intended for people who think ministers sit down with a colossal in-tray and go through every piece of paper flowing into their office. In fact they have large staffs of advisers, liaison officers and media people to handle their paperwork.

And the whole point is that, if you’re going to rort something, you make sure the minister doesn’t have direct oversight of it — staff (who, conveniently, can’t be called before Senate committees) do it.

Gaetjens tries to bolster his case with the bizarre observation that there was a gap of a few weeks between the spreadsheet being developed and the grant decisions being made. Um, Phil, the spreadsheet listed marginal and targeted electorates.

That’s not exactly a list that shifts from week to week. It was based on the 2016 election results and what the government thought it could win. So what if it was developed three weeks before decisions were made? It wasn’t going to change.

Finally, Gaetjens offers his own maths to show there was no rorting.

But notice what metric he’s using. He only mentions numbers of grants. Nowhere in his letter does Gaetjens mention money.

You’ll search in vain for a $ symbol. But the money is the important thing. You can fund six projects worth $5,000 each in a safe electorate but also fund two $200,000 projects in a targeted electorate. The ANAO’s metric is where the money went. Let’s remember its conclusion.

You’ll also look in vain to find Gaetjens anywhere acknowledge that McKenzie’s office demanded nine ineligible applications be funded, using a “emerging issues” exemption in the program guidelines, except her staff “did not demonstrate how these applications reflected ‘emerging issues’ or addressed priorities that had not been met”.

Guess where those applications were located? “Seven of the projects were located in a Coalition held-electorate and two in ‘targeted’ electorates (one held by Labor and the other by an independent member).”

Gaetjens’ slipshod reasoning, selectivity and efforts to distract from the real issue reflect a couple of things.

One is that the bureaucrats in PM&C who drafted his letter for him don’t have a good grasp of grants administration (understandably — it’s a central agency, not a line agency).

The other is that Gaetjens has spent so long as a staffer that whatever rigour he had as a public servant seems to have been replaced by the need to protect his boss.

WHO is PHIL GAETJENS?

Who are these people?

They get squillions $$ from us – surely we have a right to know who they are and from under what rock they have come-IPA?

“WHO is PHIL GAETJENS?”

My thoughts exactly.

And did this guy ever have “credibility”?

“The ensuing reaction has damaged Gaetjens’ reputation”

Did he have any sort of reputation to begin with?

McKenzie didn’t have any whiteboards to use. They were being used by Michaela Cash

At this stage, it feels farcical – something not even worthy of a political comedy because it’s too far-feteched.

Is the take-home lesson here that the government feels the electorate can be appeased by such a half-arsed partisan action, or is it counting on the apathy that’ll come from how much this is dragging out? Or something else entirely, perhaps? I have no idea anymore.

For a better idea, Kel, might I suggest reading the article by Roni Salt, in this very edition of Crikey.

Put this, and that, together, and you have a much fuller picture

And, personally, I found Salt’s reference to the “bullshit bus” to be very worthy.

I read both (and several others before it), but I still have trouble understanding the strategy now that the media is firmly focused on the rort.

The media aren’t firmly focused on the rort – they’re firmly focused on the POLITICS of the rort.

Go all the way back to Michael Bradley, in here, when he was one of the very few to wonder aloud about the LEGALITY of the rort.

And, what’s happened since? Almost exclusive focus of the politics of the rort.

And, so it churns, as it (now) always does.

Much of the media is trying to mitigate the fall-out as it hurts the Coalition they pimp, by spreading blame to “they’re all doing it”?

Like they all “screwed the $multi-billion tax-payer M-DBA to suit their irrigator mates”? Or “used a quarter of a billion ($100,000,000 + $150,000,000) tax-payer dollars” in an attempt to buy votes?

That this all started with Labor’s Ros Kelly and her white-board?

Who will remember, or have shits to give, come the next election?

Not the people who count – those in potential swing seats.

You are clearly rorting if you use “other factors” and “emerging issues” clauses without careful explanation.

They’ve totally lost this one. No-one believes the excuse or justifications.

At this stage, it feels farcical – something not even worthy of a political comedy because it’s too far-feteched.

Is the take-home lesson here that the government feels the electorate can be appeased by such a half-arsed partisan action, or is it counting on the apathy that’ll come from how much this is dragging out? Or something else entirely, perhaps? I have no idea anymore.