Today marks 45 years since five Australian journalists were murdered in East Timor. Reporter Greg Shackleton, sound recordist Tony Stewart and cameraman Cary Cunningham worked for Channel 7. Reporter Malcolm Rennie and cameraman Brian Peters worked for Channel 9. They were all in their 20s. The two crews arrived in Timor separately but linked up at the small village of Balibo near the western border with Indonesia.

In October 1975 the Indonesian military was conducting a terror campaign against Portuguese Timor, as it was then called. Its aim was to capture small enclaves just inside East Timor, mount small offensive actions from them, and make the Timorese position untenable.

Its actions would generate atrocities that could be falsely attributed to pro-independence East Timorese forces. Indonesia would then be able to portray its invasion as merely restoring order. It regarded the presence of any foreign journalist as a “hurdle to be got over”, as the British ambassador to Indonesia reported, because “the only limitation on clandestine activity now appears to be its exposure”.

The five Australians would have exposed the Indonesian military’s lie.

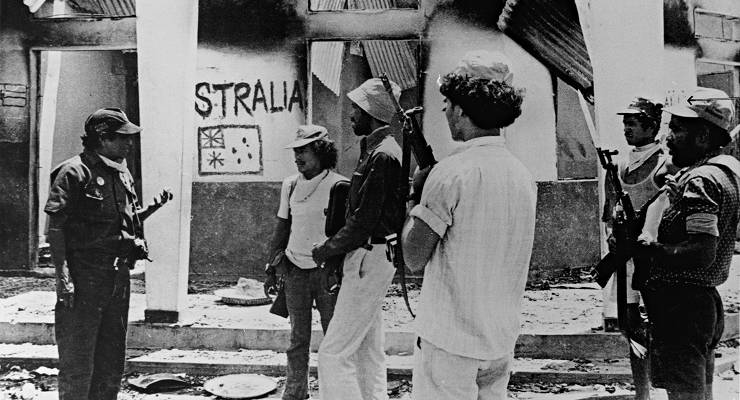

Indonesian special forces captured them on the morning of October 16 and killed them in cold blood. They dressed the corpses in military uniforms, placed guns beside them, and took photographs of them in an attempt to portray them as legitimate targets.

A NSW coronial inquest in 2007 disclosed an Australian Signals Directorate intelligence intercept in which Indonesian forces reported that “the bodies” of the five Australians had “been reduced to ashes”.

Indonesian strategists gave detailed advance warning of their military operations to the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. The Australian government has admitted that it knew the Indonesians would attack Balibo but not that the journalists were there.

In her Walkley Award-winning book, Circle of Silence, Shirley Shackleton says that her husband Greg “did not expect to be deliberately harmed because of Prime Minister Whitlam’s greatly lauded friendship with the Indonesian President”. That was a reasonable expectation in those heady days of “batik diplomacy” between Whitlam and Suharto.

A former Australian ambasador has written that an Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) officer informed him about the murders the next day. But what did ASIS know beforehand? Could the journalists have been warned not to go to Balibo? Serious questions remain about an ongoing coverup.

I have sought answers to this question in the archival record. In a case at the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), ASIS first claimed that to even confirm or deny the existence of ASIS records about Portuguese Timor in 1975 would “cause damage to the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth”.

It later admitted it possessed such records but insisted on continuing non-discloure. Attorney-General Christian Porter issued a public interest certificate allowing ASIS to make its case in secret. A public interest Certificate is self-executing; the AAT has no choice but to hold a secret hearing, preventing me from testing ASIS’ claims fully under cross-examination.

The extent of ASIS’ foreknowledge remains a secret. It will take a political decision by a future Australian government to come clean and declassify the records.

What happened to the East Timorese? We know that the Indonesian high command was so concerned about a negative international reaction that they halted their operations.

But the Australian government maintained a public silence for five weeks. Indonesia took this non-reaction as a green light; it understood it could treat the East Timorese as it wished. And that is precisely what it did.

East Timor suffered a death toll of 31% of the population, perhaps the largest loss of life relative to the total population since the Holocaust. Apparently this covering up isn’t contrary to the “public interest”.

Hmm, there seems to be nothing the Australian government loves more than a good cover up of our less than honourable approach to timor leste over leste over the years.

Interesting anecdote about how this period of history has been treated in the australian education system.

When I was in year 10 in 2004 we had to write an essay addressing the question “was the Australian government’s response to the atrocities in east timor principled or pragmatic?” Pretty much everyone replied that it was pragmatic because we were saving our relationship with Indonesia. In retrospect it’s clear that the way we were taught to think about the whole situation was that a couple of hundred thousand deaths in timor leste were preferable to standing up to indonesia.

Indeed, our relationship would have recovered from us standing up to Indonesia. Instead we decided to adopt the role of regional lickspittle.

The satanisation at began 30 years ago has extended well beyond my arguments with teachers of social studies. It was the eve of where emotions were becoming superior to facts. Only two (that I can recall – and female at that) changed their views when confronted with the non-standard line.

I have an embargoed post on this very point. The description presented in the article is anything but the last word.

I am sceptical about ASIS having any unique information about the Balibo Five. The main source of Australia’s information was DSD (now ASD) intercepts.

It was Australian Government policy to

want East Timor integrated into Indonesia. Gough Whitlam thought small states were untidy and also thought (with no basis) that the Timorese wouldn’t object to joining with their fraternal brothers across the border. No one in Foreign Affairs ever tried to persuade Whitlam that this was a flawed policy.

Somehow the Indonesian military thought they could meet Australia’s requirement to integrate Timor but without using force (completely unrealistic) by running undercover hearts and minds campaigns, all of which were inept.

The attack on Balibo was to reclaim territory from the Independence Party, Fretilin, in the name of APODETI, the very small pro-Indonesia party whom they were going to claim to have mounted the attack. . However the Indonesians were caught out by the Balibo Five who witnessed the cross-border attack by the INdonesian military, not APODETI forces . (No one would ever have believed APODETI to be capable of such an attack but Indonesian seemed to think it would give it a fig leaf of respectability)

The Indonesian Government was embarrassed by the killing of the Balibo Five and pretended to know nothing about it. It took two weeks for Jakarta to ask the local military what had happened to the newsmen, after receiving many representations from the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. That is when the military on the ground told them that the bodies had been incinerated.

Then the Indonesians decided to go ahead with a full-scale invasion and they gave Australia what turned out to be 10 days warning and asked Australia to get Australians out of East Timor as they didn’t want a repeat of the Balibo Five.

Roger East, another journalist, refused to leave and he was executed as the Indonesians landed at Dili.

The whole saga was a shameful episode

In Australian foreign policy and many saw what the outcome would be.

Thankyou, Clinton, for another cracker of an article and for your tireless efforts to uncover the dirt under the carpet.

Crikey, please give us more from Clinton. How about an article about the ‘rules-based international order’ we hear so much about, how it is supposed to work in theory, how it has worked since 1945, and the role of the West (especially the US and the UK) in trashing it whilst simultaneously using it to justify military and economic attacks against smaller nations. Maybe make that a series of articles.

Gough Whitlam told Greg Shackleton that it was dangerous to go to Timor Leste (East Timor, at the time) – face-to-face – because the situation was unstable and the Australian Government could not guarantee his safety. Shackleton decided to go. Jose Ramos Horta took Shackleton and his colleagues to Balibo and left them there.

And 45 years later we are allowing the same thing to happen in West Papua. I am ashamed of our Governments position with Indonesia. The Indonesian Government needs to be held responsible for those murders and genocide in East Timor and West Papua and I will not shut-up until that happens!!