Note: this article discusses suicide and self harm.

While it is a temporary relief to his supporters, UK Judge Vanessa Baraitser’s rejection of US attempts to extradite the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange does very little for the core principles of protecting whistleblowers and freedom of information.

Baraitser rejected almost all of the arguments put forward by Assange’s lawyers, dismissing their position that the charges of espionage are politically motivated, that the “right to truth” cited in UN resolutions had any legal weight, or that Assange would receive neither a fair trial nor first amendment protections if tried in the US.

Baraitser refused the extradition request on the basis that, given Assange’s mental condition, the prison system in the US simply couldn’t keep him safe.

“I find that Mr Assange’s risk of committing suicide, if an extradition order were to be made, to be substantial,” she said.

“Faced with conditions of near-total isolation … I am satisfied that the procedures [outlined by US witnesses] will not prevent Mr Assange from finding a way to commit suicide.”

Those procedures include “special administrative measures” (“SAMs”), conditions imposed on certain prisoners to “protect national security information”, which the judge found was likely to be applied in Assange’s case.

Witnesses for the defence described the conditions of other prisoner subject to “SAMs” thus:

Inmates were in solitary confinement, technically, for 24-hours per day. There was absolutely no communication, by any means, with other inmates. The only form of human interaction they encountered was when correctional officers opened the viewing slot during their inspection rounds of the unit, when institution staff walked through the unit during their required weekly rounds, or when meals were delivered through the secure meal slot in the door. One-hour recreation was offered to inmates in this unit each day; however, in my experience, often times an inmate would decline this opportunity because it was much of the same as their current situation. The recreation area, in the unit, consisted of a small barren indoor cell, absent any exercise equipment.

In her 132-page judgement Baraitser concluded that it did not seem possible

… to prevent suicide where a prisoner is determined to go through with this. Others have succeeded in recent years in committing suicide at [Federal] jails … As Professor [Michael] Kopelman stated, suicide protocols cannot prevent suicide, and, as [defence witness Maureen Baird] put it, “the suicide prevention strategy of the [Bureau of Prisons] is very good but it doesn’t always work”.

This raises the question — just how safe is the US prison system for someone with serious mental health issues? The answer: we really don’t know. The US prison system’s statistics around deaths in custody are hopelessly out of date, last published in 2016 and covering the period up to 2014.

But to the extent we know anything, it’s not good. According to an investigation by NBC Washington, there are about 300 suicide attempts in federal prisons each year, around a dozen of which are completed. This — again, according to the out of date figures — is a lower rate than state prisons and considerably lower than local jails where, in 2014, 50 out of every 100,000 prisoners died by suicide, a figure that was sharply rising.

Assange’s ally Chelsea Manning was hospitalised after an attempt at a federal jail in March 2020.

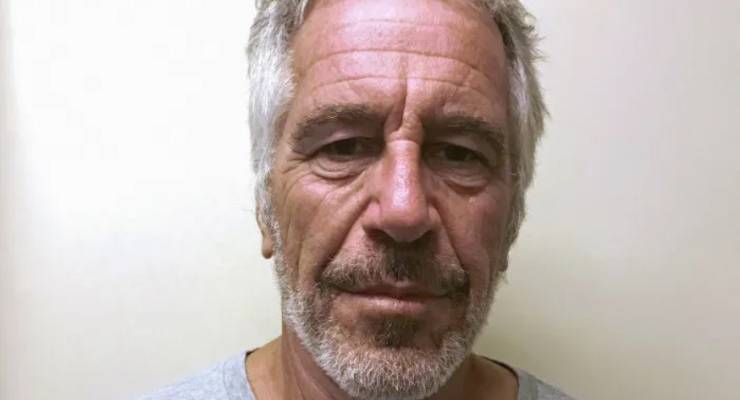

And, famously, billionaire paedophile Jeffrey Epstein took his life (under strange circumstances) at New York’s federal Metropolitan Correctional Center in August 2019.

The “serious irregularities” that surround Epstein’s death are apparently not uncommon in the US prison system according to David Fathi, director of the National Prison Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. He told NBC: “In most prisons and jails I’ve seen — and there are exceptions — suicide prevention is a joke.

We have seen people able to attempt suicide while supposedly on constant suicide watch. We’ve seen people taken off suicide watch because staff thought they were OK, and then kill themselves that same day. We’ve seen officers who were supposed to be watching someone on suicide watch actually sleeping.

For anyone seeking help, Lifeline is available on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is on 1300 22 4636.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.