Early data out of Israel, which has become a real-life vaccine trial for the rest of the planet, appears far more positive than the Australian media has bothered to report. Strange, since the Israel experience will inform the world on how quickly it will be able to deal with COVID-19.

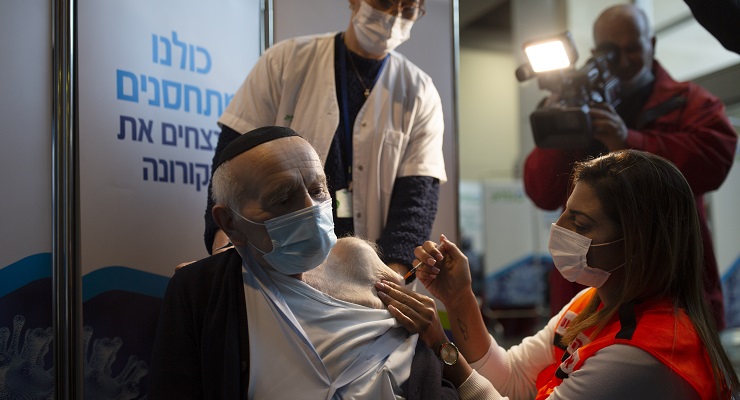

The pace of vaccinations in Israel is, in relative terms, staggering. In just five weeks, 48% of the population have had their first shot, and 16% have had their second. (The next best is the UAE, which has vaccinated 25% of its residents. The UK is at 11% and the US at 7%.)

Australia, meanwhile, hopes to begin vaccinations in late February after the Therapeutic Goods Administration approved the Pfizer vaccine earlier this week.

Israel was able to secure so much vaccine so quickly because it is believed to have paid US$30 a shot (double what other countries have paid). The investment is likely to have an incredibly high return on investment. Yet the few Australian outlets to cover the Israel vaccination spree have focused on the allegation that Israel has been vaccinating its citizens before those living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. (Palestinians in east Jerusalem have been receiving shots.)

Nevertheless, it’s likely that Palestinians in the West Bank will receive their shots before most Australians. The Israeli Health Minister Yuli Edelstein said: “It is our interest — not our legal obligation, but our interest — to make sure Palestinians get the vaccine, that we don’t have COVID-19 spreading.”

While it’s too soon for the data to be definitive, the most positive aspect coming out of Israel is the response to the second shot. The Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer says patients who received their second shot saw their antibody levels jump six to 20 times higher than they were after the their first shot (although it should be noted that the dataset was only 102 people).

Even better is the observation that the antibody levels in patients who received a second shot were so high that vaccinated people were unlikely to be carriers or infectious.

KSM Maccabi Research and Innovation Institute, an Israeli healthcare group, reported a “significant decrease” in coronavirus infections among people aged over 60 in the weeks after vaccination.

The news wasn’t all good though. One report, from the Chalit Research Institute, indicated that in a group of patients over 60 who received just one dose, the decrease in positive cases was only 33% after two weeks. This casts doubt over the wisdom of the UK’s decision to leave a 12-week gap between shots.

In any case, the Israel data raises a critical question: what is the benchmark for success? Is it herd immunity, which essentially means the disease no longer spreads, or do we just need to stop people from (potentially) dying?

If it’s the latter, even with Australia’s limited supply of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine we should be able to vaccinate virtually all the at-risk segments of the community (the more than 3 million people aged 65 and over, or with pre-existing conditions) by May.

‘Yet the few Australian outlets to cover the Israel vaccination spree have focused on the allegation that Israel has been vaccinating its citizens before those living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Haven’t you just confirmed this ‘allegation’?

Lets hope that nasty woman teacher they dragged back here was vaccinated.

So, the Melbourne lockdown prevented a more virulent strain getting out into the world.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/29/dodged-a-bullet-melbourne-lockdown-may-have-prevented-more-deadly-covid-19-variant

Still waiting for Adam to make any acknowledgement that his honkings about lockdowns, herd immunity and the Swedish model might have been wrong. Coward. Crikey is day by day losing any credibility in its claims to be ‘different’ to the MSM in its lack of accountability and goldfish memory.

When discrimination against five million of the people you rule is actual state policy as currently implemented, is a report of its existence and implementation an ‘allegation?’ Asking for a friend.

Let me guess – “Cheap tickets to Israel”?

The use of the word ‘spree’ always rankles, especially when used to describe the actions of a mass murderer on a ‘killing spree’. Here, it also evokes an unfounded, celebratory optimism based on jumping early to wishful-thinking conclusions which are later contradicted by more reliable data than that contained in the linked articles. Adam has never been circumspect enough to wait, and so, as Crikey’s resident expert virologist-epidemiologist, has got everything he’s written wrong in the last nine months. He ought to apologise.