Headlines highlighting concerns with the AstraZeneca vaccine, from blood clots to efficiency, have been front and centre for weeks.

One in The Sydney Morning Herald reads “I’m not anti-vaccine: why Genevieve is waiting for Pfizer” and last week articles about the young nurse who developed clots after getting the AstraZeneca vaccine dominated front pages. After hyping health concerns for weeks, the SMH posted its survey results on alarming levels of vaccine hesitancy.

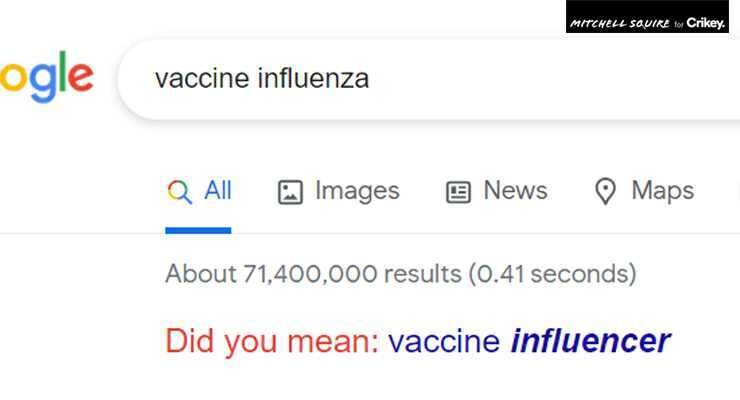

Audiences are lapping up the negative news: since late February, the top 10 new articles on Facebook about the vaccine have centred around health concerns and prominent vaccine critics.

Hesitancy makes news

In those top 10 Facebook posts since February 17 that mention the vaccine, 7News’ “Yohan Blake ‘would rather miss Tokyo 2021 Olympics than take COVID vaccine'” takes fourth place, followed by One Nation’s “Say no to vaccine passports” piece and four articles on vaccine health concerns.

Professor at Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre Alex Bruns says outlets always look for controversy.

“Conflict tends to be the major focus of reporting because it’s a well-recognised news value,” he said. “There is some degree of attention to anything that might be uncertain, that might cause conflict, and that might result in public debate.”

While there was some overreporting of concerns around blood cots, there was also a very fine line between reporting and sensationalising.

“If that’s not handled very cautiously and carefully and ethically, then it might increase hesitancy and increase public concerns [and] probably cause some confusion,” he said.

Quest for info can fuel conspiracies

While overreporting blot clots are a concern, so is underreporting. During times of uncertainty, people search for information and answers and if they’re not readily available they may look in the wrong places.

“When there’s not really completely conclusive information out there, people start looking for explanations or even rumours and unfounded and unverified information in all the wrong places,” Bruns said.

“There’s very fertile ground at this point because audiences are really quite concerned and possibly more ready to believe stories that tell them that everything’s falling apart.”

The idea that everything is falling apart is a popular one, says lecturer in social psychology at Melbourne’s La Trobe University Dr Mathew Marques. People like bad news.

“People are often motivated to respond when there is something negative rather than positive,” he said.

Bad news combined with uncertainty can fuel conspiracy theories, although Marques says thankfully — and a little surprisingly — no major conspiracy theories around the vaccine in Australia had emerged.

“The government is usually the target of conspiracies because it’s a powerful authority figure and for some people they’d be the conspirators or the puppet masters,” he said.

The fact we haven’t seen more major conspiracies emerge was likely to be down to ethical news coverage, he says.

“There have been quite a few stories indicating the failures of the government … But there’s equally as many positive stories encouraging people to get vaccinated and providing clear messaging around vaccinations.”

Case in point from the Guardian (23/5), major headline “CDC studying reports of heart inflammation in young Covid vaccine recipients”. Oh no, on top of all the rampant blood clotting and so on. But wait, a reading of the text (but who has time for that nowadays, honestly) and one finds that the CDC “had not found more cases than would be expected in the population”. This relentless (and false) highlighting of low vaccine efficacy, pointless exaggeration of league-table differences between vaccines, disproportionate dwelling on exceedingly rare serious side-effects and amplification of minor scientific and medical disputes into into major doubts which are hard for non-experts to evaluate, has got to be resisted (especially by editors who get to write the headlines). We know that conflict, dispute and catastrophising sells news, but there are actually more important things at stake.

Donald

Yes I could not believe the headline combined with the text comment.

The combination of experts advising against <50s getting AZ and the puerile irresponsible ability of the media has done a lot of damage. But much of the media abandoned any idea of social responsibility decades ago.

The media has certainly played up any thing medical related it can find that may cast a doubt over having the AZ vaccine.

They do not wait for proof of any sort – just rampant speculation or inference. Accurate information – yes , but innuendo and scare tactics – no. Does not the media have a professional ethics body or such which can bring them into line??. If not , then it is time that such did occur.

If Albanese was running a scare campaign on AZ, Morrison would be all over him.

Curiously, with an impending election, Morrison has said and done nothing about the unbalanced information coming from the mainstream media. But then he didn’t do anything about Craig Kelly either so no surprise. He is acting according to his electoral calculus.

Morrison and Hunt are actively undermining the vaccination program (if it can be called a program), having decided to make a virtue out of its failure by ‘pivoting’ (it’d be a ‘backflip’ if Labor did it) to a later ie. mid-2022 reopening of the borders. That period conveniently takes in the next election. The postponement into a blurry future itself undermines vaccination by making people think they have time and, if the other vaccines arrive ‘by Christmas’, choice. ‘It’s a free country’ says Smirko, ‘plenty of time’.

I will not forget the PM telling us to go to the footy & to let covid 19 rip. He always gets his own way in the end. There is good reason to fear this corrupt cabal posing as a government.

I had my first vaccine jab on Wednesday. My son had his on Monday. PLEASE everyone get vaccinated. It may not be the last vaccine we will need. Covid 19 is a fast moving enemy. But at least you will have the best weapon we have against it at present. F*** this government & its hatred for anyone not considered profitable.

At one stage last week, ABC News had two concurrent headline articles about concerns of the safety of the AstraZeneca vaccine. It’s hard not to see that constant attention to the downside of the vaccine and not have it play on your mind, even with all the maths that puts it into proportion.