Days after the final Australian troops left Afghanistan, the man who first sent them there 20 years ago says the government must grant visas to Afghans who helped the defence force (ADF) during our longest conflict.

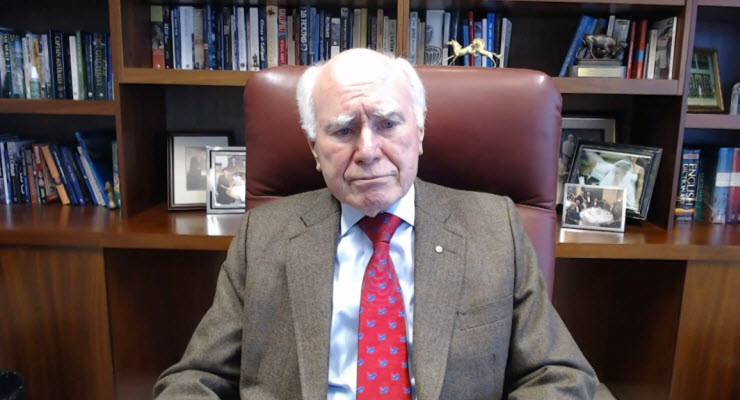

Former prime minister John Howard told SBS Australia has a “moral obligation” to provide asylum to the thousands of people who were critical to Australia’s war effort.

It’s a major intervention from a Liberal elder statesman, and one which will put further pressure on the Morrison government to fast-track the evacuation of Afghan translators, local staff and their families as the Taliban advances through the country. And it highlights growing concern, including from within government ranks, that a situation everyone agrees is a humanitarian crisis is getting out of Australia’s control.

Howard speaks for the Liberal Party

Most politicians agree Australia has a duty to protect Afghans who helped the ADF. But with the Australian embassy closed, and troops now gone, there are fears a distant Australian bureaucracy is being outrun by the Taliban advance. So far, around 240 Afghans have come to Australia since the withdrawal was announced in April. Hundreds still remain in Afghanistan, often living in hiding and separated from their families.

Many of those are contractors who worked with Australian troops but might not have had a direct employment relationship sufficient to satisfy local decision-makers. According to Howard, however, such distinctions shouldn’t stop us granting visas.

“I don’t think it’s something that should turn on some narrow legalism,” he said.

“If a group of people gave help to Australians, such that their lives and that of those immediately around them are in danger, we have a moral obligation to help them.”

Howard’s stance is also shared by many in the government, with Coalition MPs now more openly calling for Australia to urgently do what it can to resettle Afghans. Liberal MP Phillip Thompson, who is an Afghanistan veteran, told Crikey he wanted the process to move faster.

“We can always be quicker, we can always do better. I do and have encouraged us to move a little quicker,” he said.

The process means people like Sameer* — who Crikey reported last week helped remove landmines, and who has clear documents showing his relationship with Australia — are left in limbo. In Sameer’s case, the wait has been five years.

“If you’re removing landmines, you come to Australia. If you’re digging IEDs out of the ground, you’re one of us,” Thompson said.

On the other end of the Liberal Party’s broad church, moderate backbencher Fiona Martin wants Afghans granted visas, saying Australia “must get this done.”

“Those Afghans who were brave enough to support our soldiers and fight for a better life for their country deserve our protection,” Martin tweeted.

Where have Payne and ScoMo gone?

So far, much of the work to bring Afghans to Australia has happened out of sight — with departments working largely in secret for security reasons, and pressure being placed on ministers behind closed doors. Now, the government is at least starting to openly talk about the situation more, something Howard’s intervention will likely accelarate.

This morning, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said he agreed with Howard’s comments.

“This has a high level of urgency within the government,” he said. “We’re doing that as fast as and as safely as we can.”

But there’s still the perception among advocates that Foreign Minister Marise Payne, who has considerable responsibility for the program, alongside Defence Minister Peter Dutton and Immigration Minister Alex Hawke, hasn’t fought hard enough to ensure Afghans are granted visas.

Today, Payne agreed that Australia had a moral obligation, and told the ABC the government wouldn’t leave anyone behind, so long as they’re “properly eligible and checked”.

But she also indicated contractors, who Howard said should be allowed in, weren’t eligible for priority special humanitarian visas, which are reserved for those who worked with military and diplomatic staff. Rather they are eligible to apply under the regular humanitarian and protection visa stream for all Afghans under threat from the Taliban.

That distinction locks out people like D*, who worked on a crucial Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Aid project and has since heard 15 of his colleagues have been murdered by the Taliban.

Grilled about his case, first reported in Crikey last month, Payne pointed to “privacy and security” reasons why she couldn’t comment.

*Names withheld for security reasons

When John Howard is the voice of reason and moral conscience in this situation it just shows how morally devoid and corrupt this current group of ‘ministers’ truly are.

The difference between him and them is that he’s no longer desperately scrabbling for votes. When he was, he was no more the voice of reason and moral conscience than Scummo is.

Except that, even in extremis, he is still the same dissembling, Lying Rodent.

Why would any self respecting medium give this canker of the body politic the oxygen of self serving publicity?

Is he staking a claim for a State funeral?

Great comment

Couldn’t agree more Jess M

That Morrison and his government are prepared to leave these people behind shows the character of the man and his government yet polls show that he is by far our preferred PM.

That in turn doesn’t say much about the character of modern Australia.

Howard has no moral authority here in my opinion as he was part of the lie that sent our troops to IRAQ in the first place.

I’d say Australia has left them behind already. Hard to get out when we don’t even have an embassy there any more.

Aussie! Aussie! Aussie! Oi! Oi! Oi!

Every day, in every way, so much more to be ashamed of!

I’m 72yrs old and brought up in an era when you stood beside your friends.

Time to have an honest assessment of what Australia has become.

Retired Australian Special Forces troop commander Mark Wales

“If we were willing to run a war there for 20 years and to throw all the resources at that, then the least we can do is throw the resources and the time at making sure the people that helped us get out alive and unharmed for what they did,” he says.

“Raise an emergency cell [response team] that goes to the people, because we have a moral obligation to do it in a process and quickly.

“I don’t see why we can’t at least remove them from the country and have them processed and prioritised into Australia – I think we owe the country that.”

Dutton … “made no apologies” for the time it was taking to process visas and would not be giving “blanket approvals”.

Forsaken Fighters founder and former army captain Jason Scanes h…. said Dutton was now “playing politics” with people’s lives.

“No one in their right mind would suggest that security vetting should not occur and that’s not what we’re asking,” he says.

“These interpreters assisted Australian troops on the front line and as it stands in Afghanistan now, the front line was everywhere.”

Scanes said his organisation was tracking a much larger number of cases than the government has released, with about 200 Afghan interpreters, 140 embassy guards, and many other locally engaged staff, including AusAID project contractors, in need of visa assistance.

He said he was in regular contact with most of those listed, many of whom are now in hiding and running out of places to shelter as violence continues to grip the country and regions fall under the control of the Taliban.

Some Afghans have been waiting months – others years – to have their visas processed. Even those approved to resettle in Australia have had to join a queue with tens of thousands of Australian citizens waiting for permission to enter, after Home Affairs confirmed the Afghans are subject to overall capped number allowed in hotel quarantine.

Nothing like a co-ordinated process for visa processing has been put in place as Australia exits Afghanistan and the Taliban looks poised to take over much of the country.

Retired admiral Chris Barrie was chief of the Australian Defence Force when then prime minister John Howard committed to the invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001…by Kate Banville TSP

And we (us and the Afghanis) are only in this immoral mess of mayhem because of Howard’s ego and politics, multiplied by his insatiable appetite to please and ingratiate himself with Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and co.

“A war without end strategy”?

Howard on “moral obligation”? FFS, after :-

“Non-core promises”?

A “Ministerial CoC” – that he made up to gull voters pissed with Keating – that he had to be dragged kicking and screaming over a couple of weeks to apply to Prosser, before others : but never Reith?

The knifing of his own Coalition Speaker Halverson – for being too fair?

“Children Overboard”

Invade Iraq (and take resources from the war in Afghanistan) on the pretext of “Saddam’s WMDs and terrorism sponsorship”?

Hicks, Habib, Haneef, Assange?

AWB?

NPA (Note Printing Oz)?

The buggery of East Timor?

Etc?

Give over “Honest” John – you’ve every bit of gravitas for lecturing on morals as the mould for Morrison, in his hypocrisy.

Does anyone really think that the Australia led by an amoral Prime Minister feels any obligatioon to those brave man and women who helped us and saved our troops in Afghanistan?

They slammed shut the embassy and withdrew our troops without taking their interpreters with them.

Such an honorable series of actions.

Well Morrison and the Taliban both use the Torah.

Bit of a stretch.

Not untrue though.

The Coalition under Howard, Abbott, Turnbull and Morrisin are terrorizing Australian residents without any accountability, and their aim is to silence whistleblowers and keep their filthy corporate driven murderous deeds secret.

”In 2007, New South Wales Supreme Court judge Michael Adams found that two ASIO officers had kidnapped a young medical student who had been charged with terrorism offences in 2004. That implausible case was dropped, but no ASIO officials were charged with kidnapping.

A Coalition government introduced a new law in 2014 making it a serious criminal offence for whistleblowers to reveal anything about a botched “Special Intelligence Operation”, although it allowed ASIO and its “affiliates” to commit criminal acts other than murder and serious violent offences”….Brian Toohey, The Saturday Paper July 17th 2021

There is an article in today’s TSP which is a must read, like most of Crikey’s articles, and which of course will reach few readers compared to the mania that is Murdoch and Credlin the Queen’s favourite for birthday honours this year. Howard was the devoted hand servant of Bush and between the two of them they caused the torture and murder and maiming of thousands on a known lie.

Howard at the same time was taking care of farmers wheat and feeding the enemy and handing over millions in bribes to have the enemy fed to Hussein. I refuse to believe he has acquired a shred of conscience over those now being tortured by Ismlamists.

Howard and his gang of thieves, liars and murderers have turned this nation into a subservient lapdog of the USA and is quietly waging war on Australians who may threaten their power. Crikey’s articles on the militarisation of our nation by the Coalition are complemented today with one in the TSP by Brian Toohey

”In February 1978, a bomb killed two garbage collectors and a policeman and injured 11 people after exploding in a garbage truck compactor. The bomb had been in a rubbish bin at Sydney’s Hilton hotel, where 12 foreign leaders and then prime minister Malcolm Fraser were meeting. Fraser did not introduce special terrorism legislation. Nor did he brand Labor as soft on terrorism.

Today, there are at least 83 terrorism laws, many containing harsh new offences and powers. Ignoring habeas corpus, the Howard government introduced a law in 2003 allowing ASIO to detain and compulsorily question people for a week. They didn’t need to be suspected of any crime, but might have information about terrorism. Refusal to answer incurred a five-year jail sentence. In 2005, the Australian Federal Police was empowered to take people into “preventative detention” for up to two weeks and impose a form of house arrest, called a “control order”, for up to 12 months without court approval.”

It is not often that I agree with John Howard but on this occasion I do. I am glad that he has spoken out on this matter.

Hopefully those who hold power in the Federal Government will listen to him.

My heart really goes out to all those Afghani’s who quite rightly fear the ‘hell of Earth’ that awaits them when (unfortunately, not ‘if’) the Taliban return to power.

ABC headline

Veterans burn medals to protest Australia’s ‘failure’ to protect Afghan translators from the Taliban

Should read

Veterans burn medals to protest Morrison’s ‘failure’ to protect Afghan translators from the Taliban

This creature using the word “morals” is obscene !

He’s staring death in the face and thinks pretending to care will fool his imaginary god

It’s generally against my conscience to wish someone an imminent death but Howard tests that. I have assuaged my ill feeling by wishing him an extended stay in aged care.

I used to hate JWH with a passion but have discovered a new level of passion when it comes to Morrison, Dutton, Payne and Cavanan to name but a few!

I certainly hated the bastard while he was PM, but he’s just an insignificant nobody now and I don’t care enough about him to hate him. Anyway, every Liberal PM since him seems to have been worse than the previous one – although none of them have done the damage that Howard did.

One curious thing about Howard’s reign was that he finally killed the unofficial white Australia policy. Until then, it was almost impossible for black people to migrate to this country, but he turned that round – as evidenced by the large African and Indian communities that began to appear in cities like Sydney and Brisbane during his government’s time.

And he killed it to assuage the greed of his supporters.

And before Howard I hated Malcolm Fraser with a passion. But after he left politics Fraser found the strength to resign from the Lib Party, follow a different path and criticise the Libs.

I don’t wish him pain and suffering – I can’t stoop to the LNP level- but I do wish him gone as a symbol of Liberal Greatness to be wheeled out and shoved in our faces at every opportunity. Dementia would achieve that, but I lost my Dad to dementia and can’t bring myself to wish it on anyone’s family. Peacefully passing away in his sleep would do me. Tonight would be good. Last night would have been better. Several decades ago before he met Menzies would have been best.

Pretending being the correct word, I do believe the man who supported the coup and waited around the back while Kerr overthrew Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser found in his latter years a shred of conscience that had been dormant for so long in his psyche. Howard however, never had one.

It’s not just Howard, it’s the whole Liberal National Party deadly virus that has democracy under threat.

Under Turnbull, ”Authoritarian changes gathered pace after parliamentarians acquiesced in the Australian Federal Police’s raid on Parliament House in 2016. They accessed IT systems and seized thousands of non-classified documents to search for the source of leaks to a Labor opposition frontbencher. The leaks revealed problems with rising costs and delays in the national broadband network – information that should have been public. In an earlier era, ASIO and the AFP would never tap phones in Parliament House, let alone raid an institution at the pinnacle of Australia’s democratic system. The parliament’s failure to find the AFP in contempt only emboldened the police.” Brian Toohey TSP

It’s hard to believe that he wouldn’t choke using the word – more likely it has been attributed to him to save him from the fate of Manius Aquillius.