The Biosecurity Act, as I’ve noted before, is an extraordinary law that gives the executive arm of the federal government powers a dictator would find enticing and the people would, ordinarily, find terrifying.

COVID-19 is not ordinary and we have all become accustomed to being told what not to do. That includes extreme restrictions on freedom of movement. We assume, as citizens, that one of our inherent rights is to come and go from our country as we please, but we’ve accepted that that carries an obvious public health risk.

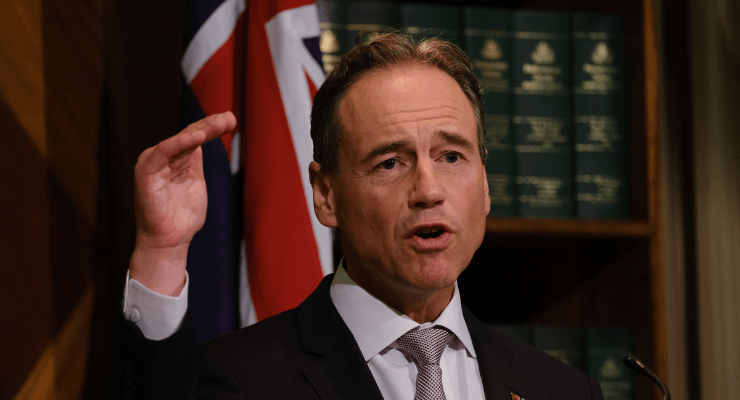

Since March 2020, it has been the law, pursuant to a determination made by Health Minister Greg Hunt using his powers under the Biosecurity Act, that Australian citizens and permanent residents cannot leave Australia without an exemption, which is only supposed to be granted if they can show “exceptional circumstances”, defined as “a compelling reason to leave”. The practical application of that rule has been opaque and, many of us suspect, arbitrary.

The determination gave a number of blanket exemptions to certain classes of traveller, meaning they didn’t have to apply for a specific exemption. They included citizens and permanent residents who are returning to the country where they are ordinarily resident: expats.

Last week, without publicity, Hunt amended his determination by removing the general exemption for these people. As from August 11, they are required to seek a specific exemption before they can leave Australia to return to their homes overseas.

Naturally this triggered pandemonium among Australian diaspora; nobody wants to come back here if there’s a risk they won’t be able to leave again and get back to their homes, jobs and families. But of course many people have needs to come here temporarily.

As soon as the panic began, Home Affairs Minister Karen Andrews was publicly saying no problem, every expat will get an exemption. According to an explanatory statement issued by the government, and confirmed by Andrews since, the problem it is addressing is that a small number of people have been engaging in “frequent travel between countries”, placing pressure on the hotel quarantine system.

As Andrews said: “These restrictions provide a balanced approach between allowing Australians to travel, if essential, while protecting community health.”

OK, so we know why it’s been done. The restriction cannot be legally valid unless it is directed towards, and justified by, the federal government’s constitutional responsibility for quarantine; the government has no legislative power to prevent Australian citizens from coming or going otherwise (except in case of war, or to ensure compliance with an international treaty obligation).

The claimed link to quarantine is that every time someone leaves Australia they want to come back again, and that affects the limited quarantine system as well as adding to the COVID risk generally.

However, while for Australians who live here the usual case is that they go overseas and then come back, for expats the opposite is the norm: they live over there, come here temporarily, and then go home. Imposing a restriction on their ability to leave here can have relevance to quarantine only if it is designed to deter them from returning here in the first place. That is, at best, tenuous. It’s also disingenuous.

Andrews is insistent that it’s just a box-ticking exercise; everyone will get their exemption, nobody will be trapped here unwittingly.

That leaves us with two possibilities: Andrews is right, in which case the imposition of an exemption requirement on foreign-resident Australians is a completely pointless waste of time and energy; she is wrong, in which case foreign-resident Australians are in fact going to be deterred from exercising their inherent right to come home.

Further, on the government’s own admission, the problem it claims to be addressing has nothing to do with the movements of most of the hundreds of thousands of Australians who live overseas; rather, apparently, it is a small number who’ve been coming and going like yo-yos. We can legitimately think that that is not OK, in the same way as we can wonder how Brian and Bobbie Houston got a special exemption to travel to spread the Pentecostal word.

Well, if so, then it would be easy to make a rule, using the health minister’s extraordinary powers, to put a cap on the movements of these few frequent flyers. There is no warrant in that to make life harder for the entire expat community.

The Biosecurity Act mandates that before the minister imposes any restriction he must be satisfied that it is likely to be effective, it is appropriate and adapted to the purpose, and it is no more restrictive or intrusive than is required. That is, the minimum necessary to achieve the purpose, which the minister has confirmed is to reduce the pressure on quarantine and restrict the spread of COVID in Australia.

I fail to see how this latest measure satisfies any of those tests. At best it’s lazy bureaucratic overreach; at worst, it’s a coded message to our own citizens abroad: don’t come home.

I am totally puzzled by all this. Am currently at Timber Creek, NT – 300 kms from the WA Border on the Victoria Highway (turn left from Katherine). While waiting to check into the caravan park I got into conversation with a charming young Italian gentleman who told me he had arrived in Perth two weeks ago, leaving his (I assume natal) family back in Italy. He told me that he is enjoying his travel and hopes to travel around Australia. Good luck to him – he is the kind of person one would have met routinely before Covid. But now? What about the 39,000 permanent residents who are stuck overseas because of limitations on quarantine places. Or the unknown number of Afghan allies who face death if we don’t get them out?

There were 39,000 at the beginning of the pandemic and 39,000 now read the first comment which gives some clues

Maybe they only want to come home when their jobs become redundant +probably because if covid).

Don’t worry. Des and his ilk will find a way to blame them for their own sacking.

We’re not just expats. We’re Australian citizens and that gives us the right to get back home if we need to. And ‘need’ comes in many forms.

Yes like the Indians who brought back Delta with them after they had gone back home to get an arranged marriage spouse or attend a religious festival or leave their children with the extended family for a visit

Truly the citizens of convenience. All of the rights, none of the responsibilities of leaving behind dodgy cultural practices.

In the 70s the phrase multicultural society was first introduced because multiracial was too radical.

It was the basic of that faith that “all cultures are equal” which is demonstrably untrue.

Most immigrants leave their home country to have a better life which is, in large part, only possible because the culture of this country differs in small, irrelevant ways such as rule of law, enforcement of contract & property, liberty of individual conscience, M/F equality and freedom of, if not from, religion.

he is not taking away the right to get back home – you just cannot leave at a whim when you think your holiday is over and go back to where you really live

Bex and a long lie down required!

You still believe that? Our citizenship isn’t worth excrement.

This doesn’t prevent you from returning to Australia. It just means that you are subject to the exact same restrictions on leaving Australia that all other Australians are subject to.

So how do you justify those?

Not that I have to justify anything to you, I don’t like not being able to leave Australia either (I usually spend months in Asia each year seeing family) Complain to Scummo not me. Why should there be exceptions for Expats? The “Expats” should never have been able to leave Australia when other Australians can’t. One rule for everyone.

Greg Hunt is another one who is corrupt and so full of secret agendas I wonder how he reconciles them all with what he was elected to do. This amendmentment is a criminal act. What are the options for putting him in the dock to defend it?

He comes like Christian Porter from a political family history which means they have never worked for a living and have sucked off taxpayers all their lives full stop in the case of the porter family that is more than true

I can’t seem to shake the sense that government is intent on a smaller Australia, averse to its citizens and visitors alike. A kind of ‘we say who will come here and in what circumstances’ gone off the rails. I will make my call when (if) we see the unusual* restrictions lifted. NZ has done the same thing, with the result that the answer to everything is to complain about not being able to get staff.

*based on Anne Twomey’s comment on 7.30 last year, that while Australia’s travel restrictions are not illegal, they are certainly unusual, as in the kind of decision a place like Azerbaijan might make.

Agree, too many Australians of Anglo/Irish heritage have become inculcated with white Australia sentiments via proxy issues of blaming refugees, immigrants, NOM and population growth for everything, and especially to avoid environmental regulatory constraints on fossil fuels etc..

Now we have media giving voice to those asking for a ‘solution’ to environment, unemployment etc. by keeping borders shut permanently, except for the ‘top people’.

Actually they are giving a voice to the White Australia views that bubble under the surface of the majority of White Australia. The environment etc is just a convenient excuse.

I grew up in a progressive upper class environment. I went to a lefty uni course. All very well and good. Then I moved to a tightly held ethnic ghetto. It changed my views on immigration to be around people who had no interest in liberal values like LGBTQ, women’s rights, caste equality and more. I have no idea why the left defend these communities so much when they are against everything the left is meant to stand for. I felt I had been sold a lemon for agreeing with multiculturalism for so long when those very people did not like my existence.

Many Australians, white or not, are rightly suspicious of immigration from culture that’s are in direct opposition to our hard fought for liberties.

My background is Anglo-Saxon and I grew up in multiple Working Class areas that today would be called “Multicultural” but in reality the only thing we had in common was that we were all from somewhere else. It taught me tolerance and respect for other cultures as well as an understanding that it will be the children of Immigrants that “fit in” rather than the generation that emigrate.

I willingly spent time in the military and funded my own University education (3 times) – No government assistance. I spent years living in what would be described as an Upper Class White Suburb in Sydney’s North Shore which taught me how racist (mostly unconsciously but not always) White Australians are. That was before I married someone from another culture and realized how much Australia is stacked against Non-English speaking immigrants.

In all that time, I witnessed the emigration of refugees from Vietnam and other countries and watched the vast majority of them work hard, educate their children and “fit in” without losing their culture. They certainly worked harder than “Australians” were prepared to (and still do) but that has never been good enough for a vast majority of Australian’s who think that Australian means White and are holding on to values from the 1950’s and blaming others for their own failures.

“wage theft cases foreign born”? While there are some, you have forgotten about CBA, Woolworth etc who have massively underpaid workers. It’s the unyielding requirement for English (which is not the official “National Language” of Australia in either the Constitution or Federal Legislation) that disadvantages immigrants and refugees (yes they are different but the Anti-Migrant crowd bundle them as one) along with our Draconian immigration system. A lot of Employers and immigrant workers are simply unaware of Australian pay and employment standards because of a lack of education in these areas.

“Vaccination hesitant” I’m not surprised given that the various English-speaking White Governments either don’t provide information in multiple languages or provide outdated information. Regardless, an awful lot of “Australians” are also Vaccine hesitant for entirely different reasons – apathy and a lack of community and Government pressure.

There are immigrants from all walks of life however it is those that are disadvantaged in terms of education and language that struggle because of the systems we have in place. Again, we are happy to have them do the jobs that “Australians” are too bloody lazy to do but not when it doesn’t suit us or they rise above their “place”.

Everyone, without exception, in Australia is either an Immigrant or descendent of an Immigrant.

I don’t care what color you are. Plenty of non-white cultures have very compatible values.

I care when people move here and decide to do things like cover their faces and the left looks the other way and abandons women. There is no such thing as the cultural defence to crimes against groups like women.

“Plenty of non-white cultures have very compatible values” – do tell and please provide an explanation of “white culture” as well. “Australians” seem to object to all immigration (except if the immigrants are white of course).

“cover their faces and the left looks the other way and abandons women” – so we can add Religious intolerance to the list as well. As to abandoning women, that is not the sole prerogative of Immigrants. Plenty to go around on that area with the existing White Australia “culture” that’s for sure.

As to “the left”, you really need to look at the current far right Limited News Party Crime Sinister “Hillsong” Scummo Morriscum and his ilk as an example of women being abandoned along with all pretenses of, you know, actual honest government.

Blaming other nations and/or immigrants for our problems is a recurring tactic that was particularly popular in a certain European country in the 1930’s and 40’s you may recall and look how that turned out. It’s also alive and well and thriving in Australia.

Australian is a Nationality not a Race.

I support progressive Western values. I oppose groups that stand in opposition to that be they happy clapper Hillsong loonies or people from Stone Age cultures. I won’t apologise for standing up for gay rights women’s rights, abortion, no forced marriages and so on.

I don’t care what color people are. Plenty of white people contribute negatively to this country (those happy clappers!). My issue with the left is they are often reluctant to defend our hard won progressive values against incompatible foreign cultures.

As for religious tolerance, I don’t have to be tolerant of intolerant religions. That’s absurd. It goes for all religions including the darker parts of Christianity.

I’ve spent a lot of time with cultures in this country who oppose progressive western values. It’s not pretty and it doesn’t belong here.

“Progressive western values”? Like Genocide, invasions of Sovereign nations, economic coercion, war crimes etc all of which “the West” glosses over and refuses to accept (but hypocritically picks on other non-Western nations for allegedly doing). I have heard this spouted time and again from the Right (who I note are overwhelmingly White) as “justification” for attacks against a minority of Immigrants and Refugees. Again, if you are White they don’t care. Don’t kid yourself, I see the racism from White Australia every day and have experienced it firsthand while dealing with our Draconian Immigration System.

Those are right wing Western values.

Progressive western values include things like LGBT rights. When non Western cultures are homophobic you find people become uncomfortable to call it out and say those values don’t belong here, drop that element of your culture.

People are very comfortable to tell white people what negative elements they need to drop, like white male misogny. When it comes from another cultures let’s all look the other way.

The tolerant must tolerate the intolerant but not the intolerable.

The intolerant have no such constraint and seek to impose their intolerance upon any and all who prove to be susceptible.

Such as the decadent West which can’t even be bothered to breed in sufficient numbers to pay the taxes to fund the about to boom pensioner cohort – the age pyramid of Europe is no longer that shape but resembles a circus fat lady, tiny feet struggling to support a massive torso with a huge balloon head.

I don’t really mind either way how many people live here.

I do note that the pandemic has proved some of what they said about migration is a lie. We’ve had it drummed into us that it’s all skilled skilled skilled and contributes so much.

Ok, so why then did the pandemic expose that large areas of cities were ethnic ghettos that were low income, low education, large families, large homes and adverse to getting vaccinated? If immigrants were all so educated and successful why are they all simultaneously so poor in such large numbers? Could it be that they really exist to lower wages at the bottom end?

Why when they shut down the public housing tours in Melbourne did we hear from residents who had lived there for 30 years, arriving as young people? Why haven’t they moved on with their lives into private homes if the program is such a success?

Why are so many of our wage theft cases foreign born?

Australia has a lot of room and we could help out the rest of the world by taking more in. That’s fine. But you have to wonder when so many are poor what the real goal of immigration is.

You give lots of evidence, Camille, that Australia does not welcome the skilled or the unskilled.

The ‘othering’ that goes on as a way of humans sorting out who we are and aren’t, gets baked in by the divisive messages all governments use to control their populations (easier to manage the kids when you keep them fighting among themselves, right?). Not so different to the rest of the world, though, the othering has been ramped up over the past 4 decades. Now Australians are completely absorbed deciding who can and can’t belong and why. No wonder it’s noisy and fractious living here.

Once was the time P. Keating was advocating that Australians finally start to meet our real time neighbours – Indonesia, Phillipines, Malaysia, Singapore and at the time, English skills classes and ethnic radio and ethno specific support services truly embraced ‘having a go’. Not so, now. Either you find some way to squeeze yourself into the PM’s notion of a ‘quiet Australian’ or you are unAustralian.

As I see it, at the moment, it is feeling distinctly unAustralian to want to leave or enter Australia unless you are in the exempt class of being a friend of LNP/ multi millionaire.

It’s a good topic to knock around though because the thing we won’t get from any government here is discussion about the Australia people would like to have – I think all our governments religiously use every opportunity to stir prejudice and bigotry and if they are stuck (which is often), create more drama by piling on to cover their indecision and lack of governance.

I work a minimum wage job. When I complain about people (who are often white and western) coming here to deliberately work for less and drag down the bottom end living conditions I’m told by the progressive professional class I’m being unAustralain or letting myself be divided. You try working in an industry where newcomers drag down conditions we’ve fought over 100 years to have.

I don’t care if people come here and play by the rules. We do need more workers in areas like disability and aged care. But don’t come here via visa fraud, live 6 to a room and work for $10 less than minimum wage.

Big deal. This just brings them into line with other Australians/Permanent Residents who are unable to leave Australia without an Exemption.