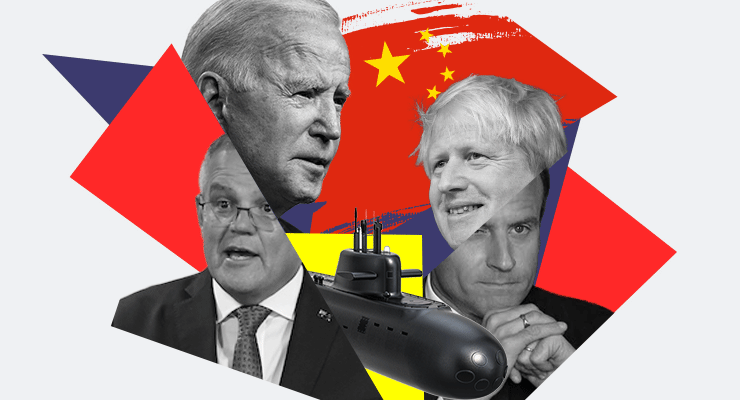

From the moment of that strange press conference — Joe Biden flanked by two screens showing ScoMo and BoJo, for all the world looking like some performance art piece — it was pretty obvious that the new AUKUS alliance wasn’t really about the submarines.

No doubt that was what the Australian government wanted to lead with, at least for Australian domestic consumption — yet another chapter in our demented cargo cult about one class of ships, now running into its third decade. Since the early 2000s and the construction of the six Collins-class submarines, which still wheeze on in service, “submarines” have been a symbol of magical thinking about our defence needs and capabilities.

Submarines are intended as an auxiliary force to protect a navy proper and civilian shipping. Trouble is we have no navy proper. We have three destroyers and eight frigates, and after that it’s coastal craft. This is not a force that can defend a coastline such as ours. Thus the AUKUS boosters billed and cooed about the silent, deadly power of the nuclear-attack subs, these sleek beasts of the undersea, acknowledging, indeed celebrating, that their role would be well beyond our local waters as part of what is laughably being constructed as a defence against China, and is actually the encirclement of it. Our valiant subs would be an indispensable part of multinational defence, etc, etc…

Trouble is, this confrontation with China has also been constructed as occurring now. In the inevitable comparisons with World War II, we are being told we’re in the 1930s. And our first subs weren’t and aren’t going to arrive for 15 to 20 years — rather late for the rematch with Hitler/China.

Furthermore, the US has more than 50 attack-class subs and 18 nuclear-missile subs, and is committing 60% of its forces to the Indo-Pacific region. This notion of being a vital component by those plucky little fellas Down Under is all obvious spin.

No surprises who the spin is for either, as we explored last week. The DCNS French subs deal has been collapsing quietly, then more loudly, for some time. With $2 billion already spent on non-nuclear subs — nuclear boats refitted to run on diesel, body odour and cunnilingus, being French and all — and with suggestions the private contractor was gouging us on upgrades, cancellation of the deal had already been talked about.

Had such been done, the most likely course of action would have been to buy or lease subs the US or UK were upgrading, which could have been ready for service in years, not decades. But that of course would have raised the question as to why the Coalition had committed to the fantastically expensive and complex French deal in the first place. Now, instead, we’re talking defence, binding in the opposition and realigning the debate along a whole different axis. That is quite a win — unless it starts to look too clever by half.

The US and the UK were happy to let us have this angle, even though the AUKUS agreement, which of course no one outside the bubble has seen, is really about something quite other than territorial warfare per se. As the breathless leaders’ statement on it indicates, this is about the meshing and integration of high-tech development and deployment (robots, pilotless air- and sea-craft, cyber warfare, space warfare) in such a way that de facto materially abolishes the nation-state command division altogether. Questions of command that arise for olde-worlde forces like crewed submarines are the least of it.

It’s obvious that to work effectively in a conflict situation, the three or five or eight subs we had to contribute would need to be under US command as part of a larger force, no matter how that was dressed up. Still, some fig leaf of autonomy could be maintained. But with the more advanced forms of warfare that AUKUS has been designed for, that possibility disappears.

There is a unified military process — you can’t sail your part of the code out of an ex-ally’s harbour; you might find you don’t even have actual command of your own ships or planes any more — that is not merely a new alliance, but which contemplates a wilful dissolution of national sovereignty under new conditions of geopolitics. Hopefully, hope to God indeed, our signatories understand this. But they probably don’t.

The nation-state, created in 1648 to achieve peace in Europe by granting a self-determining interiority to nations, cannot survive unaltered in the networked era, when the world-system from comms to transport is so radically borderless. But giving up the sovereignty that remains to a military alliance is only one way to respond to the new conditions, and it is the most craven.

Any alliance contemplating such a tech-meshing and integrating is thus going to need to be anchored by a mix of deep-shared interest and a commonality — or the appearance of such — that runs deeper. If you’re going to “share” tech at an ever-deeper level, then it obviously can’t be with an alliance such as “the Quad” — this ad hoc uniting of India, Japan, the US and the little fellas Down Under, in pursuit of, as we may have mentioned, encircling China.

Japan may eventually decide that it has no choice but to accommodate China; India and China may eventually form a grand alliance against the West, especially if they eventually decide it is in their interest to replace the US dollar with a new global reserve currency. The US won’t be sharing tech with them. But the three-way “special relationship” is made for such an enmeshing. Its actual grounding in shared ethnicity and cultural traditions is more branding than real; the US would conceivably bomb us if that would gain it some of our agricultural markets.

The US-UK Atlantic relationship has been bruised and battered by the failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the growing distrust of the US by many of the British public. Indeed, it looked as if Joe Biden — very pro-Irish and anti-Boris Johnson — was shaping up to be the least pro-UK president for quite a while. But was that some sort of double bluff while a more comprehensive deal was stitched up?

Biden’s desire for an alliance against China in pursuit of a return to “rules-based order” — heavily slanted in favour of the West — has been oft-expressed. The south must be ruled out. But so too, it would seem, must be the EU. Germany is still dependent on exports to China for its prosperity, and the Belt and Road Initiative is increasing China-EU trade at a cracking pace.

If the US doesn’t trust the EU regarding China, it would have a major interest in breaking any link between Australia and France, as the latter remains a Pacific power. It would have been ridiculous to mobilise NATO in the Indo-Pacific with the EU about to announce its own common defence plan. The US doesn’t want equals in its new alliance, but subordinates who look like equals. Australia has played that role for decades, knows it by heart. But the UK? Well, AUKUS from its end forms part of a new post-Brexit “global Britain” push. What could be more global than policing your old imperial waters? Does it actively want to do that? Maybe. Maybe not. But what it needs from the US is a free trade agreement.

Biden had said that the UK was at the back of the queue, especially if Brexit wrecked the “Good Friday agreement”. They may have just shuffled quite a bit further up it now. Thus AUKUS — contradictorily bound together by unspoken Anglo racial solidarity but also denying it, an alliance that is really a cover for the US to conduct itself in a way that would prove impossible to do in an actual alliance. And all in pursuit of a strategy that may amount to the US getting itself the best global settlement before it quits the hemisphere and accepts that it will have to, at best, share the century with Asia.

Which would leave Australian defence — which has a dubious interest at best at being in the South China Sea — like those cargo cult subs we’re forever waiting for: perpetually under construction, very high, very dry.

The USA is no friend of Australia – to them we are useful idiots! Given America’s history just over the past 60 years we should NOT be one of the 5 Eyes. They would betray us in a heart beat if it suityed their purpose. Do not trust !

They have interfered, bullied or attacked just about every Country on the Planet. They interfer in Australian politics!

An A-Z of the countries that the USA has interfered with in the name of “freedom” by assassinations, coups, meddling in internal politics, supporting dictators, jihadis, terrorists or just plain straight out invasion…

Afghanistan 1979-1992: 2003-

Australia 1973-1975 and still meddling

Albania 1949-1953, 1991

Angola 1975 to 1980s

Bolivia 1964-1975

Brazil 1961-1964

British Guiana 1953-1964

Bulgaria 1990

Cambodia 1955-1973

Chile 1964-1973

China 1945 to 1960s

Congo 1960-1964

Costa Rica mid-1950s

Cuba 1959 to 1980s

Dominican Republic 1960-1966

El Salvador 1980-1994

East Timor 1975

Ecuador 1960-1963:

France/Algeria 1960s

Germany 1950s

Ghana 1966:

Greece 1947-1950s:1964-1974

Grenada 1979-1984

Guatemala 1953-1954:1960-1980s

Haiti 1959-1963: 1986-1994

Indonesia 1957-1958: 1975

Iran 1953: 1979-

Iraq 1990-1991: 2003-

Italy 1947-1970s

Jamaica1976-1980

Korea 1945-1953

Laos 1957-1973

Libya 1981-1989 and still meddling

Morocco 1983

Nicaragua 1978-1990-

Panama 1969-1991

Peru 1960-1965

Philippines:1940s and 1950 but also early 20th century

Seychelles 1979-1981

Suriname 1982-1984

Syria 1956-1957: 2009-

Uruguay 1964-1970

Venezuala 1895.1908-1935, 1948-58, 2002-

Vietnam 1950-1975

Zaire 1975-1978

‘…we are useful idiots…’

That’s an accurate summation. Australian governments play the role seamlessly (except under Whitlam).

The only circumstance that saved Gough W from being assassinated is the fact that Australia has a parliamentary system of government. So if the top dog is ‘removed’ his deputy moves into the empty chair. Removing Gough W as an individual would not have achieved the desired result.The entire government had to ‘go’ and it was ‘booted’ … at the stroke of a pen. Look at the list above and try to calculate the number of Presidential assassinations.

And we get articles by historical illiterates harking back to some mythical halcyon days of moderate Liberalism; it NEVER existed, since federation conservatives have opposed ‘liberal/progressive’ legislation and human rights in all forms, safety nets for society, be they aged pensions unemployment single mothers etc etc let alone the right to housing, health, education, equal pay etc etc, all opposed and never initiated by any conservative regime .

Please add Hawaii.

Good piece raising the level of the debate. I’d always accepted (not necessarily agreed with) the view that the main purpose of Australia’s defence forces was as auxiliaries to US forces and this was inherent in their design. Other matters, coast guarding, gun boating and as disaster relief forces, were secondary. However, seeing this as now becoming marginal to broader and even more sovereignty releasing integration in cyber warfare and what this might mean in terms of risk and consequences for Australia, is a step-up in analysis.

in broader terms Australia is moving closer to being a feasible site for battle exchanges that don’t threaten the homelands of China and the US and therefore trigger nuclear escalation. This was the possible fate of Europe during the Cold War. Those wars for us could be trade, something more physical and cyber. In the short to medium term the government appears to have chosen we should run more risk and incur more costs as part of a new accomodation with America.

Unfortunately we also know the Govt making these decisions is lazy, incompetent and primarily focussed on electoral politics. It doesn’t look like a good decision and is even less likely to be so because it is Smirko and co. making it.

Becoming the collateral damage isn’t particularly attractive for the most trusted ally in my book.

I’m convinced that the main purpose of Australia’s defence forces as auxiliaries to US forces is to give our forces basic on site target practice against people who obviously don’t matter ! ( don’t matter to the neocons that is). It obviously doesn’t matter either to the Australian war mongering politicians who send them for their taget practice.

And – -all this time the MSM has shut up about the killings & unlawful invasions etc. And- – -of course we would never send our military into a”real war” where the enemy was capable & well equiped. Only 3rd world thanks .

Yes, for the US we the canary in the Indo-Pacific coal mine.

Australia’s military has never had the capability to defend our shores. Rather it was always designed (and openly admitted within military ranks) to be a guerilla resistance force in the event of invasion. In the 1980’s the eye was on Indonesia.

Pretty much as Kenneth Mackay predicted in The Yellow Wave (1895), where he describes Australia unable to make a conventional armed resistance to invasion and its colonial overlord too busy elsewhere to give any help.

Basically the agreement to hand over our Defence capability to the USA, to dispose of it as it wishes, is a cover for Morrison junking the French Submarine deal which was always a crock of poo.

Australia’s benefit for the USA is in Intelligence sites, bases and storage of USA defence material, training ground for USA military, an attempted distraction for China and a safe haven for the well off American who will move here in droves after any US/China conflict.

The whole idea, whilst in line with the USA’s so called strategic wars, against Korea, Viet Nam, Iraq, Afghanistan and a number of other places is stupid. The USA has not delivered real peace and stability anywhere.

What happened to the “War on Terror” , has it suddenly gone away, so that a war employing much more weapons, munitions and other stuff that American manufacturers can profit on, will eventuate?

How is Australia going to cope without the major buyer of our minerals, the major supplier of our consumer goods and no real manufacturing base of our own.

It is hard to imagine a worse trio of Allied leaders than Biden, Johnson and Morrison to take us into the next decade.

The contract may have been a “crock of poo” but weren’t we the ones who wanted to diesel power the existing nuclear powered version? Aren’t we the ones who wanted to continually want to alter to developments in weaponry? Weren’t been the ones that had no idea how to specify the scope of sonar. In fact, wasn’t it true that Australia was, or should have been the party doing the specs.

To come out now and rubbish the French is typical Morrison. The guy is a total incompetent.

Didn’t the French get the contract after we upset the Japanese by not buying from them, after Abbott had glad-handed their PM and told him it was in the bag?

Who hasn’t this government annoyed yet?

I can imagine a worse trio, replace Biden with Trump and you have the 3 horsemen of the apocalypse.

I think Morrison is channelling his inner Trump. Morrison virtually plagiarises ideas from others that fit his dreams. After all this is the man who told us god wanted him to be prime Minister ?

my thought was that you don’t need trump in the packet if you have Morrison. But you do have a point, if we add Trump as an advisor then we have the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

Be alert and alarmed says Jennifer Wilson, and I see the similarities between Morrisin and his hero Trump in this.

Domestically, Morrison has instigated and overseen a steady decay in institutions designed to protect democratic principles, peopling them with employees who answer not to citizens, but to government.

Morrison has weaponised institutions designed to uphold and nurture democratic norms.

His latest refusal to insist on the financial accountability of non-ministerial members of the Federal Parliament is another powerful blow to democracy.

This is the first time we have seen Morrison perform on the world stage as he does at home.

His ability, indeed his ambition to sow disruption and chaos as a means of exercising his personal power, combined with his belief that he is chosen by God, is chilling.

Be, at the very least, alert and alarmed.

I don’t think he believes for one second that he is/was chosen by God, he just wants others to believe it, thinking we are all as unintelligent as him.

He’s a grifter, first second and always but with this move he has outdone himself and angered too many people.

I think Scott Morrison is totally deranged and has been since childhood, seriously I mean this to be so. And I think he really does believe he is doing his very own god’s work; his god is make believe like all gods, and his god is speaking to him in tongues every day, the man is definitely a grifter yes, he is as deranged as Jim Jones.

As the estimable Caitlin Johnstone has pointed out, this deal is not intended to protect us from China, it is to protect us from the USA. It’s really nothing but a vulgar protection racket.

The Industrial Military Complex continues to run America and we are the tag-along toadies……..still.

Industrial Military Entertainment Complex is my preferred upgraded version of the term. The popular culture industry in America is deeply embedded in cooperation with the military and tropes that support it. It produces a stream of highly profitable cultural products (fictional and in purported news) that arouse violent emotion and prejudice and characterise violence as a best solution, especially as a form of justice. Even products professing to deplore war still tend to frame it as both inevitable and central to life. And as with the MIC proper, it cannot exist without constantly identifying enemies to make its object and thus generate profits.

There was a story that Eisenhower originally wanted to describe it as the Military-Industrial-Congressional complex but was dissuaded so as not to alienate congress. But other sources said it wasn’t true. Wouldn’t have been out of place though.

avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/eisenhower001.asp

An excellent comment. The hyper-reality shows on TV–now seemingly dominant–in conjunction with the news have skilfully developed a mythology of nationalism, individuality and competition, as well as self-reliance and (scripted manipulation). The buttressing of the MIC complex is another bonus for those who control all this.

Every 7 or so minutes a bully comes on the telly and starts screaming at a contestant., it is quite disturbing, your explanation is pretty succinct, thank you.

A lot of truth in that. Robert Coover wrote a novel The Public Burning (1977) which does an astounding job of reimagining Richard Nixon’s contribution to the trial and execution of the Rosenburgs in 1953, blending in an encyclopeadic quantity of popular culture in a way that makes the USA in sum a rampaging crazy carnival where everything is aimed at entertainment and spectacle, and the crowd is always howling for more.

That was a good book. I think I read it in about 1983 and it’s still seared into my memory.

It has been reliably reported that Ike intended to say the “bureaucratic military industrial complex” until either some bureaucrat’s urgings prevailed or a typist missed a word in his Farewell speech in 1961.

An upgrade on the IMEC is an important improvement in understanding the hold the US has on the world, thank you. It isn’t that we aren’t aware of the pressure we are under, it is that it is completely snowed by the information output in the form of” entertainment” that makes it so confounding.

There is also another aspect to Morrison’s behaviour and the way he handled this so badly. Jennifer Wilson has written for The Drum etc and she rightly points out that:

Obviously, the French were never going to be relaxed about losing the lucrative submarine contract.

So why did Morrison compound the fallout by failing to inform them in a timely and courteous manner of Australia’s changing needs?

He did it because he could.

He did it because the exercise of raw power is his drug of choice.

Morrison is never as energised as when he is in full authoritarian flight.

He had power over the French.

He had power over the Americans.

He is now responsible for the acrimony between the two countries that has caused the French to recall their ambassador from the U.S., for the first time ever.

I do believe what we’re seeing now is Morrisin becoming more and more unhinged and Trump-like, refusing to care about any blowback to us and our nation – it’s all about him being in the limelight and that light is all about him retaining power, he is a certifiable psychopath.

A previous poster may pointed out an interesting juxtaposition of pics of the Donald and Mussolini, both posing for photo ops at : http://www.thehypertexts.com/Donald%20Trump%20Benito%20Mussolini%20Parallels%20Fascists.htm.

Their heads tilted back, their weak chins thrust forward, mouths closed and lips suggesting something between a smug smirk and a defiant grimace, the small piggy eyes focussed on some imaginary horizon or moronic visions of whatever…

A photo of Australia’s pretend PM in a similar pose of a wannabe strongman, appeared in an opinion piece in the Guardian Australia and triggered, my recall of the above. Scary times ?

I saw it, even if there has never been such an image.

That summation fits in so well with, as I have called them, his extra curricular ambitions for being PM. And that is the advancement of not just late Bible Prophesy, but the prophesying of one of his own Pentecostal “prophets” who said that he saw Australia playing a great role among the worlds nations. I believe that Morrison in his own convictions, which could be considered, in light of the claims he has made about himself, to be relevant in your hypotheses, as the one to bring all of them to fruition. I am talking here of course about what the world will be like post the “Rapture” and where eternal life will be gained for the chosen, the remnant. He has a goal, an aspiration, to sit in a place of high power in the revitalised Kingdom of Christ. To us mere mortals, having to deal with the fallout, that may sound like being a certifiable psychopath, but to him this is an attainable reality. Just don’t get in his way. We’ve seen this in his inexorable climb to the position he now holds. Why should it not apply in the eternal life he sees for himself, because I am firmly convinced that he does believe in it. It’s not just a front to help him politically here and now.

Imagine having to endure Morrison for eternity. I cannot but think this must be hell.

You know, LoL and all the rest of us, I’ve often looked at outrageous governments around the world and wondered “why doesn’t the populace do something?”. But now it’s happening in our own country – this appalling decision, climate inaction, blatant corruption – yet we are just as unable to “do something”.

A lot of people before the last half of the 20th century wondered why the most sophisticated, cosmopolitan, scientifically advanced, cultured and rich country went down a path of madness without discernible hesitation.

Twice.

Then we watched the Benighted States do the same thing, unfortunately with more money, more power and more toys that go bang.

Over & over.

Deciphering indeed.

“Almost comical”. Experts lambast Scott Morrison’s “crazy” AUKUS deal to buy nuclear submarine tech from parlous UK and US programs. Marcus Reubenstein finds a real prospect Australia will be used to “underwrite” the foundering foreign submarine industry.

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/has-pm-put-australia-on-the-hook-to-finance-struggling-uk-us-submarine-projects/

Considering drones ,.. as another commenter mentioned , this sounds plausible , pay back for having to buy all that ore ,minerals, and meat, veg. from us.

Except it’s not us that own it, we’re onlookers.