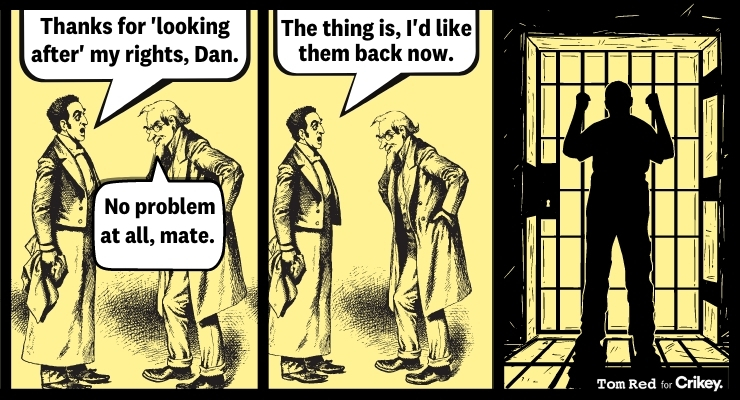

With 262 days of lockdown to its name, Victoria has been home to some of the most divisive pandemic politics in the country. Even with restrictions finally ending, nerves are frayed, emotions are high, and exhaustion clouds everyone’s judgment.

So just as Victorians were trying to forget the past 18 months, new pandemic laws have taken many by surprise.

Under the changes, the premier and health minister will be empowered to declare pandemics and impose public health orders — a departure from the current arrangement under which the chief health officer holds most of the power. People found guilty of “intentionally and recklessly” breaching public health orders would face two years’ jail or a $90,000 fine, and a minister can detain a person for as long as they think is “reasonably necessary”.

There is plenty to unpack about the laws, and a lot of the nuance has been left behind in media coverage — perhaps a symptom of a state that doesn’t want to talk about the pandemic any more, and one that is deeply divided about lockdowns, even if it still, on the whole, it supports the Andrews government.

The opposition says the powers are draconian — and there are certainly some extreme elements to the legislation. Although it improves some of the current emergency powers, there is concern among legal groups that it gives far too much power to the government without any oversight mechanism.

Victorian Bar president Christopher Blanden QC has slammed the powers as “disgraceful”, saying they will give the government “unlimited power to rule the state by decree”.

The Human Rights Law Centre was more cautious, saying on the whole they provide stronger safeguards around detention and police powers, but could be improved by including oversight.

Why now?

The government’s emergency powers are due to expire on December 15, and there has been pressure from the crossbench not to renew them — which is why it turned to this legislation.

Victoria’s heavy use of emergency powers last year was criticised, not just by the opposition and liberty groups but by senior lawyers who questioned whether public health orders should have been treated as legislative instruments and properly tabled in Parliament.

The decision to lock down public housing towers last year under public health orders was also later found to be in breach of human rights by the Victorian Ombudsman.

What’s missing?

While it’s true the laws may improve the emergency powers the government acted on last year, it’s also true they are missing key oversight mechanisms that would hold the government more strongly to account.

Dr Catherine Williams, a research director at the Centre for Public Integrity, tells Crikey that the Victorian Ombudsman would be the perfect body to ensure the rules are enacted fairly.

“If there is no review mechanism, that is very worrying,” she said. “If you’re going to give Parliament power to curtail fundamental rights and freedoms, then there must be sufficient protections in place.”

I totally agree. More oversight is key! The problem is that these new laws, similar to what’s already law in other jurisdictions, have already been politicised as draconian by Newscorp and that’s where the conversation ends.

“Already been politicised as draconian by News Corp.” Got it in one, Rob. Thank you for this sane piece, Georgia.

I learnt something during a career of dealing with emergencies, real ones, where people live or die based on what you do. It was that an emergency, let’s also call it a crisis, needs crisis management, not management by committee. Committees are great for normal, non-crisis, times. Excellent in fact. But, when a true crisis hits you need to move quickly, decisively and with authority (lawful authority that is). Why? Because it’s not normal times. It’s not business as usual. It’s an emergency, a crisis.

Like say the crisis of WMD in Iraq?

Prima facie, I have no trouble with the new laws. Call them ‘draconian’ if you like.

After observing (on television news services and not ‘live’) the insane behavior of thousands of deluded individuals who, inter alia, ran amok on the streets of Melbourne during the lockdown, fighting the police, spitting on health workers who were committing no more crime than trying to vaccinate the homeless and disadvantaged, and urinated on the walls of the Shrine of Remembrance, I have come to the conclusion that such laws are necessary.

I am not interested in the ‘human rights’ of people who readily accept lies, deception and fakery put about by those with malicious and malevolent intent. Without this criminally irresponsible behavior it is highly unlikely that the Covid case numbers, hospitalizations and deaths would have been as high as they have been in Victoria. During a pandemic it is more necessary than ever that we function as a coordinated, cooperative and coherent society and not as a bunch of selfish, thoughtless and ignorant individuals (whose behavior might have brought joy to the likes of Margaret Thatcher but to few others).

The fact that we had so many crazy people on the streets advocating lunatic ideas is a reflection of the fact that our society neglects the mentally ill in a criminally irresponsible way and at times of crisis, such as during a pandemic, that neglect comes back to ‘bite us’.

Doesn’t NSW have the same powers without any need to call a state of emergency or suffer political fallout?? Recall hearing they do during the Dictator Dan campaign which fomented noncompliance and protests with “He’s seeking unprecedented powers, He’s a dictator etc. This might be it: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2010-127#sec.7

As comments suggest, there seems to be a little too much political PR and bluster going on, to continue targeting the Victorian government and Premier, for restrictions, constraints etc. on personal ‘freedom’ (imported from the US).

However, what seems to be missed is context or comparison with LNP federal government’s propensity for draconian laws and even unvoted wars that media have implicitly supported over the years by their silence or anodyne interrogation of such issues?

Of course it doesn’t take long, saw on an online group other day (normal middle class white collar Australians), someone making the offensive comparison of the same ‘personal restrictions’ with the ‘holocaust’.

This is a symptom of those indirectly promoting, through various guises inc. LNP, radical right libertarian ideology, but needing compliant or ignorant voters and/or authoritarian attitudes, shaped by media, to oppose sensible policy, and indirectly promote bad policy.

Shaped by media yep. Here is ABC’s article: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-25/victorian-premier-parliament-lockdown-pandemic-covid/100567664 And my 30th or so soon to be ignored feedback re: their rank promulgation of LNP rhetoric: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-25/victorian-premier-parliament-lockdown-pandemic-covid/100567664 What ‘huge sweep of powers” is Andrews seeking that NSW hasn’t had since 2010? https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2010-127#sec.7 Instead of feeding the Dictator Dan seeking “unprecedented powers” narrative you could have reported on the similarities and differences between NSW existing legislation and Vic’s proposed instead of promote a divisive and destructive narrative.