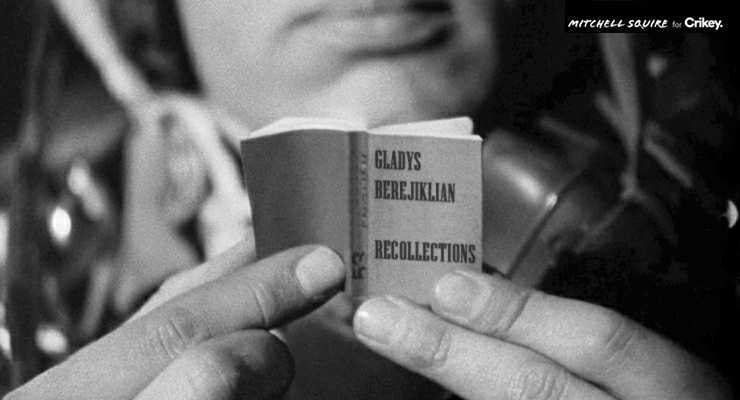

I tweeted mid-afternoon on Friday that we’ll be using Gladys Berejiklian’s Independent Commission Against Corruption appearance as a training video for witnesses forever.

I wasn’t kidding. In the course of her first day in the witness box the former premier gave a masterclass in how not to do it.

Like all litigation lawyers, we coach our witnesses — not in what their evidence should be, but in how to cope with the ordeal of cross-examination and leave the court with the clear impression they are a witness of truth.

There are rules for what to do and what not to do. Berejiklian broke all of them.

Make the obvious concession

Painful as it may be, even if it is damaging to your own case, if you’re in a hole and your choices are to dig down or up, dig up.

Counsel assisting Scott Robertson SC opened his questioning of Berejiklian with an offer:

If you were able to have your time again, would you disclose your close personal relationship with Mr Maguire to your ministerial colleagues or any of them?

The concession was so obvious it was visible from the moon; on any legal test, as a matter of common sense and as agreed by every other witness, she had had a conflict of interest obliging her to disclose her relationship with the former Wagga Wagga MP Daryl Maguire.

Berejiklian chose to dig down. She had to be asked twice, as her first answer was non-responsive, but she was then clear: given a do-over chance to make the disclosure: “I would not have.”

Much of the rest of that day’s torture, described by many media commentators as watching Berejiklian tie herself in knots and from which she emerged with her credibility shredded, would have been avoided if she had made the obvious concession.

The only answers are ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘I don’t know’

For a witness, there is only one goal when being cross-examined: get out of the box as fast as possible. The shortest route to that is by giving the shortest answers. A skilled cross-examiner only asks questions to which they know the answer, and which are designed to advance their case. You can only harm yourself in cross-examination, so the aim is keep it short and limit the damage.

This exchange illustrates how badly Berejiklian failed to follow this rule:

Robertson: “So at least as at 12 April 2018, you regarded Mr Maguire as part of your family. Is that right?”

Berejiklian: “Well, in terms of my feelings but definitely not in any legal sense and definitely not in terms of anything that I felt I needed to put on the public record.”

Robertson: “We’ll let the lawyers argue about the law, but is this right, at least in terms of your feelings, you regarded Mr Maguire to be part of your family as at April of 2018?

Berejiklian: “Well, there’s no doubt I had strong feelings for him but I wasn’t assured of his commitment.”

Robertson: “Does that mean the answer to my question is yes?”

Berejiklian: “I had very strong feelings for him but I did not, I wouldn’t have regarded him as a relative.”

Robertson: “As at 12 April 2018, you regarded Mr Maguire as part of your family. Correct?”

Berejiklian: “I had very strong feelings for him, yes.”

Robertson: “So is the answer to my question yes?”

Berejiklian: “No, I did not regard him as a member of my family. I had strong feelings for him.”

It went on. Robertson had to ask 10 more question before finally dredging out of Berejiklian the concession that, yes, she did consider Maguire to be part of her family. A simple “yes” at the outset would have saved 15 minutes of meandering, which served only to make her look shifty.

Multiple times, after lengthy responses, Robertson would ask something like: “Does that mean the answer to my question is yes?” Each time he did, Berejiklian lost another slab of credibility.

Don’t lecture the court

A witness’ sole job is to answer questions truthfully. The worst thing you want the judge to think of you is that you are trying to win your case from the box, by answering questions you haven’t been asked.

Berejiklian failed this test comprehensively. Commissioner Ruth McColl SC had to intervene six times to admonish her for not answering questions, at one point telling her explicitly to stop making speeches.

A particularly awkward moment came when, being questioned again about whether she considered Maguire to be family, Berejiklian responded, “Well, I’ve answered those questions and I don’t have anything further to add,” earning a stern rebuke from McColl to answer the question.

Even worse, at one point Berejiklian during an answer said “… and that is the, the threshold question, with due respect, commissioner …” McColl was sharp: “I think we’ll decide the threshold questions, Ms Berejiklian.” Ouch.

Don’t pre-empt the questions

In an intercepted call, Berejiklian told Maguire that she would “sack” a public servant, but not until after he fixed a particular problem. Robertson asked a generic question about whether Maguire’s interests had ever influenced Berejiklian’s decision-making about hiring or firing officials. Her response: “You played something to me in the private hearing regarding an official I made reference to. Is that what you’re asking me?”

That’s called pre-empting the question; it’s the most common, and worst, mistake a witness can make. It makes them look calculating, and distracts them from their one task: to listen to the specific question and answer it. Berejiklian fell into this trap constantly.

That’s just a sampling of the forensic reasons why Berejiklian’s testimony was a train wreck. Whether she was telling the truth — whether her evidence should be accepted — is a question for McColl to determine. My observation is only that, if she was a witness of truth, Berejiklian did herself no favours in the way she went about demonstrating it.

After listening to her evidence today, Monday, she has continued in the same combative and sometimes even lecturing manner. It’s almost as if she’s trying to show ICAC that’s she’s smarter than them and they should know it. Any impression that the adoring public had of her as a poor woman wronged by a crooked boyfriend should be gone. She is a savvy hard nosed political warrior who demonstrates all the unsavory behaviors and displays the same lack of integrity as Scotty.

God gave mankind a brain and an organ but only enough blood to use one at a time ( just my appalling SOH)

Guilty as soon of rorting by her own admission, guilty as sin of conflict of interest by her own admission, a clear example of the born to rule mentality of the conservative class, just imagine the screaming headlines in the Murdoch media if that was a labor/green or any other politician, If voters think she

s a bad example then they should take a good look at the Morrison government and its staffers, rorting, raping, lying and massive conflict of interest decisions involving billions not millions of taxpayers money If they lose the upcoming federal election and that seems more likely by the day then a newly instituted ICAC or federal investigative body will be very busy for a number of years looking into what has been going on for the last 8 years under this mob.SM doesnt lie convincingly. He is just lucky to have a corrupt party to support him and a compliant press to let him get away with it. His lies are pretty transparent to the impartial observer.

Agree!!

Agreed this will be ‘the classic training video’ of how to shred yourself. This morning’s effort was even worse : re ‘get a private phone’ etc

When I did not take my mother’s advice she would say, after something went wrong: Well, you wouldn’t be told!

I’d be surprised if no-one tried to prepare Berejiklian for the ICAC hearing but, clearly, she wouldn’t be told. It’s obviously a common failing of Australian politicians who are convinced they know best and there is only their point of view. Morrison, in Cobargo and Rome, exhibits the same “know-all” behaviour.

If only we’d have the collective wit and will to punish them for their deceptions – of themselves and of us.

Isn’t Gladys in a relationship with her lawyer who has a background in ICAC?? He would’ve prepped to to drag out the “I can’t remember” line. The other reliable attack is to feign illness.