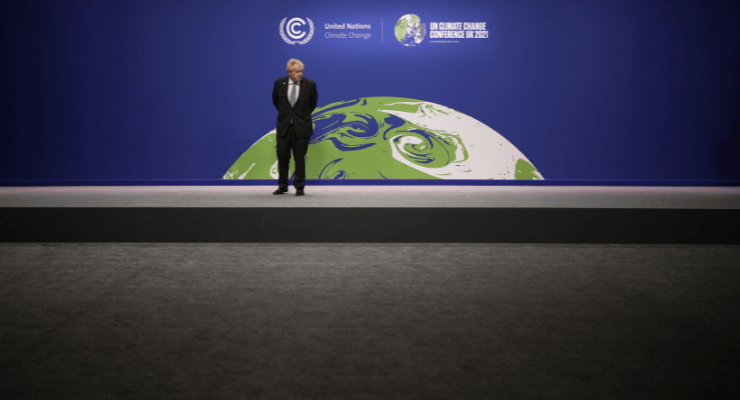

During the much-anticipated COP26 meetings in Glasgow, there will be one necessary climate solution missing from discussions: reducing our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by transforming our economic model.

Instead there will be talk of — and reliance on — risky, yet-to-be-proven-at-the-scale-required technologies and technologies that have not been invented that can save us from the emissions we continue to create in the name of economic growth. There will also be talk of the wonderful “green growth” that investment in renewable energy can generate. Anything, as long as there is growth.

Yet this much-prized economic growth is a key reason why we have released more GHG emissions since the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report was released in 1990 than throughout all of human history prior. Despite 25 COP meetings over three decades, our annual global GHG emissions are 60% higher than in 1990.

This is because gross domestic product (GDP), the proxy for economic growth, is coupled with material footprint, including energy, and therefore any growth in GDP will require growth in energy.

We are seeing this now: rebounding after the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Energy Agency is forecasting 5% growth in global energy use in 2021 and 4% growth in global energy use in 2022, 40-45% of which will be generated by fossil fuel-based electricity generation. This will take emissions from the electricity sector to an all-time high.

Not only is economic growth a key cause of our GHG emissions, it’s also hampering our ability to reduce GHG emissions in line with science-based targets. Over the past 20 years enormous inroads have been made in deploying renewable energy — today we are producing 8 billion more megawatt hours of clean energy each year than in 2000. However, over the same time frame economic growth has caused energy needs to grow by 48 billion megawatt hours.

Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel sums it up nicely when he says growth keeps outstripping our best efforts to decarbonise. Furthermore, the biodiversity crisis is just as critical as the climate crisis. Deploying more technology will further increase our material footprint, negatively impacting on biodiversity.

Growth is not only the root cause of our ecological crisis, but the key barrier to solving it.

Hickel is not alone in his concern. In November 2019, more than 11,000 scientists declared a climate emergency, and advised:

Our goals need to shift from GDP growth and the pursuit of affluence toward sustaining ecosystems and improving human well-being by prioritizing basic needs and reducing inequality.

More recently Giorgio Parisi, 2021 physics Nobel Prize laureate, echoed similar sentiments at a pre-COP26 meeting of parliamentarians in October. He advised:

The gross domestic product of individual countries is the basis of political decisions, and the mission of governments seems to be to increase GDP as much as possible, an objective that is in profound contrast with the arrest of climate change … If gross national product remains the center of attention, our future will be grim.

But don’t we need GDP growth to improve our lives? In short, no. Since the 1970s, increases in GDP have, on average, failed to translate into increases in well-being and happiness. It is entirely possible to live happy, healthy lives within smaller economies.

Robert F Kennedy eloquently summed up the inadequacy of GDP as a metric of well-being in a speech in 1968:

The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.

Simon Kuznets, the Nobel prize-winning economist who designed the first GDP measure in 1934, cautioned that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income”. GDP was never meant to be the metric of human welfare.

What could a world not solely focused on economic growth look like? It would be a world that takes climate action seriously by reducing emissions now, not relying on technology that does not exist to reduce emissions later.

We would cut our material footprint (including energy) of developed nations so it no longer exceeds planetary boundaries — of which we are overshooting six of the nine — and at the same time address the huge wealth and income inequalities across the globe.

Then developed nations will need to implement a deliberate set of strategies to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet — something which today’s economic model is failing at miserably. Doughnut economics is one way to do this.

What would it mean in substance to follow this approach?

According to Hickel, author of Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, it would essentially mean taking the best bits of life today forward — the advances in medical science, technologies needed to live a life of dignity and those to reduce emissions, and leaving the worst bits behind: polluting industries like coal and gas; armaments; red meat; fast fashion; air travel; planned obsolescence; too-large and too-inefficient homes; food waste; single-use plastics.

It would mean a reduction in advertising and shifting from “ownership” to “usership” as well as avoiding individual and corporate ownership where public ownership would suffice. It would involve having a 30-hour week so remaining jobs could be shared, and a government-led jobs-guarantee so that anyone who wanted work would have a job.

Simultaneously we would decommodify public goods and expand public services including healthcare, education, public transport, affordable housing, public libraries, parks, sports grounds and basic quotas of energy, water and internet.

The goals of doughnut economics align well with degrowth, and together show the profoundly positive possibilities of altering core assumptions around economic growth. Doughnut economics is a way of integrating social and ecological challenges into the heart of our economic system, an approach that sweetens the apparently bitter pill of degrowing Western economies.

Since 2017, the English economist Kate Raworth’s creative use of the metaphor of a doughnut for a fresh approach to economic development has captured imaginations in cities around the world. The metaphor conveys the necessity of designing economies in such a way that communities stay sandwiched inside the dough. Economic policy is guided by the goal of not falling below key essential social foundations into the hole in the middle, but not extending beyond the outer limits of the doughnut, the ecological ceiling that charts a safe operating space for humanity and the planet — a true sweet spot.

The doughnut economics framework is based on decades of scientific work on the planetary boundaries (which map the ecological ceiling) and the UN sustainable development goals (which map the social foundations). Interest in this approach tracks rapidly rising global interest in shifting economic development from a focus on sustainability to regeneration, a trajectory observable from the World Economic Forum in Davos to Indigenous communities.

Numerous city-based initiatives, as documented by the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, are trialling the application of doughnut economics for regenerative and distributive economies, from Amsterdam to Berlin and also in Regen initiatives in Melbourne (December 2020), Brisbane (July 2021) and Sydney (August 2021).

Life in this new economic framework would involve less work and more time together, less individual ownership and more sharing, less debt and more government services provided to everyone. It’s a “getting back to basics” approach with more time in nature doing things we enjoy with people we enjoy, less time working to pay for things that we don’t need or use very often.

Our lives will have more meaning because we will have a greater sense of community, cooperation and connection, rather than focusing on individualism and perpetually trying to find happiness through our next purchase, holiday or experience. We will value different things and define success differently. Life in a smaller economy does not need to mean a poorer lifestyle. Indeed, we could be richer for it.

While it would be reassuring to think we have the luxury of choice between the status quo and shrinking our economy, unfortunately we do not. Climate scientist Professor Kevin Anderson, co-author of Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven’t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve?, highlights that:

Whatever direction is chosen, the future will be a radical departure from the present. Societies may decide to instigate rapid and radical changes in their emissions at rates and in ways incompatible with the Zeitgeist, or climate change will impose sufficiently chaotic impacts that are also beyond the stability of the Zeitgeist.

The economy is a construct of human agency — it can, and should, be changed because the laws of nature are not negotiable. Leaders should treat the climate crisis with the urgency it deserves and implement policies to immediately reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, ensuring that the well-being of people and the planet are prioritised over and above the impact on GDP.

Less is more; wellbeing; downsizing; equality; Gross Domestic Happiness; excellent education for all. GDP? A worthless measure of achievement. Imprison more people and it raises the GDP. House prices go up, ditto. But it makes life easy for politicians by reducing the need for intelligent thought. Raising the GDP has become their job description. Crapping on the environment raises the GDP. Killing off 90% of insects and 50% of birds can’t be bad as long as the GDP is up. If raising the GDP produces methane and CO2 we have to keep doing it, obviously. REALLY???

Thank you for raising the subject of GDPitis. Should be more of it. Personally I’d like to see GDP go down and satisfaction with life go up. Most of it is up to the individual.

Energy production is not up to the individual.

Meanwhile, a Shell rep. tonight on TV said the company needs to keep its ‘legacy business’ (oil and gas) operating, to obtain the cash to pay for transition to renewables! Madness, it’s not about money its about mobilizing resources….. but indeed Shell will need to be compensated for the closure of its business. That’s what orthodox economists refuse to deal with. ie who will pay for the compensation of fossils, and building renewable infrastructure, on a global scale, when cash (private profits) can no longer be earned in private sector companies in the fossil economy. That’s what the fight is all about.

A thoughtful piece. But human greed will prevent common sense.

Sad, but true. Can anyone see News Corp, the IPA and the Nationals jumping on board with this, to name but three? Good ideas are one thing, but what I’d like to read is a roadmap that tells us how we can achieve these utopias against an enemy that would rather see people burned alive before they relinquished power.

Solidarity

If all the everyday people came together and demanded this, and fought tooth and nail as a collective to ensure it happens, the powers that be would acquiesce, in order to save some of their power.

And if they didn’t, viva la revolucion!

Argue long and loud enough for the certainty of defeat and you end up arguing for your own subjugation. Those people you name didn’t always have the sway they currently do and it can be taken from them. If you wait for the roadmap you will always have an excuse not to leave the house.

you’re an intelligent person Frank. What are some things you could do to get started?

You want to see a road map? Start by reading Stephanie Kelton’s best-seller ‘The Deficit’ Myth’.

Furthermore, in the up-coming federal election, you can vote for a MMT-literate party called “The New Liberals” which is also conversant with Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics”. The name of the party is a reference to the Menzies low-taxing, deficit-spending government, 1958-67, which continuously maintained unemployment under 2%!

The Job Guarantee is one of their key policies.

One might hope that common sense will prevent human greed.

I had a dream.

Utopian dream. Advertising and subsequent artificial needs run the developed world.

MSM worldwide run with ruling elites policies. Stock exchanges also rule the world as do world banks. Growth and profit is always the end result.

We seem to be running around like headless chooks wanting something to make us feel better or successful.

The social fabric/culture of many nations is very slowly unravelling. Due, I believe, to life’s constant stresses of daily living in a vague undefined as yet, total insecurity.

Who has the time and effort to think deeply of how we are living?

I’m in my mid-seventies and can’t see much hope for the future. Anarchy? Totalitarian states? Armed conflict over water, land,food?

Good sense such as this at least serves to illuminate the hopeless paucity of vision and courage in our ‘leaders’; political and corporate. What is advocated here is modern Socialism, but that cannot be mentioned because of the perversity of what passes for political and economic debate. Capitalism has been successful and enduring because of the delusions it has inculcated in us. Capitalism, fortified by politics that emphasises corporate success over human well being, has become impervious to change. Capitalism has become self-healing because government always bails it out with zero consequences for the perpetrators of economic and social shocks and catastrophes. From the time humanity collectively recognised the Earth as finite (after WW2 essentially) we have been lab rats in a death race: Either Capitalism collapses via a catastrophe that cannot be managed away with rivers of public money or the environment collapses and that causes the collapse of Capitalism.

Sadly, what is required is an international coalition of courageous and visionary leaders at a time that Capitalism has produced ‘leaders’ who are almost exclusively the cowering puppets of Capitalism. Here we are lead by a vacuous buffoon who has no imagination as Bernard has noted today.

As Runde pointed out last week, Green politics has now beaten neoliberal Capitalism. But we do not have the politics or the leaders to execute on the victory of ideas (in fact a victory of ideas over the consequences of radical self-interest).

The major political parties are now essentially redundant and lack the heart and the vision for necessary rapid and momentous change. It looks to me like a parliament of independents is the only way to create the necessary political coalitions of the future. And that will require the courageous and the visionary to abandon personal opportunity in the service of social good. That may be a fantastic hope, but how else is change going to happen?

Forget the politicians and the systems they have all failed. It requires a lot of energy but changing ourselves may be a starting point.

Thanks, BA, I was wondering when someone was going to mention the ‘C’ word and the ‘S’ word. Capitalism can’t even manage the economy without its inherent crises being bailed out every 5 to 15 years by socialistic taxpayer spending, in the form of either direct government bailouts or war. It’s positively destroying the biosphere for our children and grandchildren and preventing any intelligent attempts to save it. But we’re powerless to prevent it without acknowledging the gorilla in the room, which this article cannot do.

We are in the early stages of complete ecological collapse! We are taking near twice as much from the planet as the planet can give, and recover from, pollution has overwhelmed the ability of the seas and lands to purge and clear as it once did, we are now killing off species at a rate that equates with a “great Extinction event” – the 6th great extinction due to destruction and invasion of habitat – and, due to the massive pollution pumped into the atmosphere, the climate has entered a heating event that we are quibbling about, that could well enter a runaway event, heading for 3 degrees minimum, or anything up to 6-7 degrees by 2150.

Yet all they talk about is growth – cut back on visible carbon emissions and we can make even more production and “growth”……more money and power…….at current trends, there won’t be anyone to worry about by 2100

Absolutely John. Is it down to lack of imagination? After all Science has delivered both fact and urgency; more recently, tending to a tinge of panic? Worst case, simply don’t care about family, future generational survival? Should that be the case, what onus upon ourselves, if any?