Documents detailing the potential role of Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) agents in the 1973 Chilean coup will remain largely secret after the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) held that revealing them would prejudice the “security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth”.

It follows a four-year campaign by former military intelligence officer and UNSW Canberra Professor Clinton Fernandes to get the material declassified. And it means the extent of Australia’s involvement in the rise to power of Augusto Pinochet’s brutal military dictatorship might never be revealed.

The AAT’s decision was reached with reference to largely secret evidence provided by a series of intelligence officers under pseudonyms.

“It’s an obscenity to the memory of the victims to continue to hide the truth,” Fernandes said.

The decision

Fernandes first applied to get material on the Chile coup released in 2017. When the National Archives blocked its release on national security grounds, he appealed to the AAT, which heard arguments in June.

In reaching its judgment, the AAT relied heavily on secret evidence provided by “Jack Lowe” of ASIS and “Peter Darby” of ASIO (both pseudonyms), and Tony Sheehan from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

The tribunal placed great weight on arguments made by the intelligence officers around “mosaic analysis”, whereby innocuous disclosures about past intelligence work could be used by Australia’s “adversaries” to piece together compromising information about current national security arrangements.

The decision favourably cited Lowe’s submissions referencing online investigative journalism website Bellingcat, which used open-source information to identify Russian spies involved in the 2018 poisoning of double agent Sergei Skripal and Skripal’s daughter Yulia.

“Seemingly innocuous documents, when analysed appropriately, can reveal a great deal of information,” the tribunal said.

Because Attorney-General Michaelia Cash issued a public interest certificate at the request of the intelligence agencies, Fernandes and his barrister Ian Latham were unable to hear, test or cross-examine any of this evidence, which was given after they’d made their submissions

“It was essentially a private discussion between the AAT and the government,” Fernandes said.

The tribunal also rejected arguments that the great openness of other countries like the United Kingdom and United States about involvement in Chile should weigh in favour of disclosure.

“Protecting our ability to keep secrets — and being seen to do that — may require us to continue suppressing documents containing what may appear to be benign or uncontroversial information about events that occurred long ago,” it said.

Fernandes says this affirms Australia’s role as a “sub-imperial power”, working to assure the US that we will continue to keep its secrets.

An incomplete picture

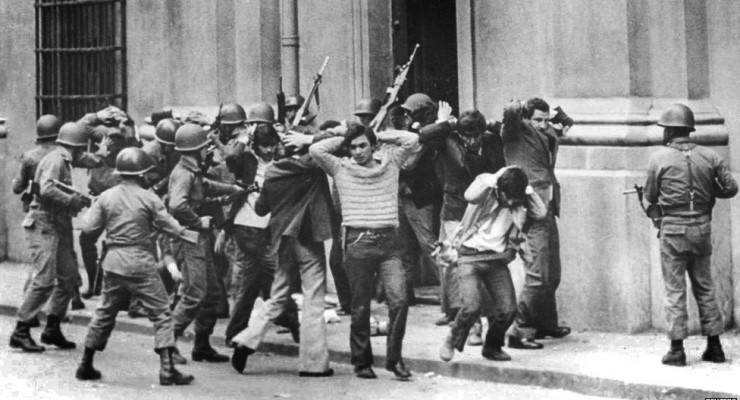

The AAT’s decision means the full extent of Western involvement in Pinochet’s coup remains hidden. When democratic socialist Salvador Allende was elected president in 1970, the Nixon administration began a campaign to “make the economy scream”, destablising the country with the help of allies to create the conditions for a military coup which the White House hoped would purge any potential leftist influence in Latin America.

The Pinochet regime would go on to murder, torture and “disappear” thousands.

It’s well established that Australia had intelligence officers in Chile during the coup. Documents revealed through Fernandes’ proceedings show ASIS established a station in Santiago at the request of the CIA in 1971, and detail how Gough Whitlam agonised over whether to close down the operation for fear of upsetting the US.

But the tribunal’s decision means what those officers did is still unknown. Fernandes has the possibility of appealing the decision to the Federal Court, which won’t be bound by Cash’s order that evidence be presented in secret. But if he loses an appeal, he could be made to pay the government’s legal costs.

The secrecy around the original hearing makes it difficult to determine the grounds for an appeal.

Chilean community wants answers

For Chilean-Australians who fled the Pinochet regime, Australia’s ongoing secrecy around the coup is bitterly disappointing. Macquarie University Latin America analyst Rodrigo Acuña, whose father was imprisoned by the Pinochet regime, suspects Australia’s involvement in Chile was crucially important to the CIA.

“A part of me expected it, and another part of me is still somewhat surprised and dumbfounded as to the decision by the Australian government,” he told Crikey.

The tribunal’s decision may have repercussions beyond Australia.

Chile is still undergoing the painful, decades-long process of bringing Pinochet-era figures to justice. One of those is Adriana Rivas, a retired Sydney nanny alleged to have helped with kidnappings for the regime, and who lost an appeal against her extradition to Chile this year.

Acuña says releasing information about Australia’s involvement could assist legal processes in Chile. It’s why he and other Chilean-Australians whose families experienced the brutality of the Pinochet regime have repeatedly written to the government demanding disclosure and an apology for Australia’s involvement. Their pleas have been ignored.

“We feel we’re entitled to an apology because we’re of the view that our universal human rights were violated by Australia and the United States to overthrow a democratically elected government,” he said.

Thank you for this article Kishor.

Reading your essay and Bernard Keane’s article on Witness K and Bernard Collaery I am, once again, feeling ashamed to be an Australian.

I recall hearing the news of the coup against the democratically elected former President of Chile, Salvador Allende and his subsequent murder at the hands of the Chilean armed forces who were working at the behest of the American war criminals Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, while I was on my way to a night school class in 1973. The fact that the Australian Government played any role in this reprehensible event is to be condemned outright. Whitlam should have immediately shut down any assistance that any Australian Government body was providing to the Americans at the time.

This incident is also only one of many that demonstrate just how ‘independent’ Australia is. It is a reminder of the fact that the so-called ‘democratic’ system we have here is only a charade. If we ever had the cheek to elect a democratic socialist government that dared to seriously challenge American hegemony, does anyone really believe that we would not face a similar situation to that faced by the Chileans in 1973?

And – should someone have not yet read it – do please visit Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits.

There are even more revelations/assertions in Oliver Stone’s ‘Untold History of the USA (Chapter 7)’ .

The red mists of rage that formed while I was reading Bernard’s piece on Australia’s disgusting behaviour spying the Timorese Government for commercial gain were just beginning to clear when I read this. Just what the hell does Australia and do Australians stand for? Has the fair go always been just a bloody myth?

There is much more where that came from too Megsays.

There was the Vietnam War atrocity, the failure of successive Australian Governments to condemn the bloodbath in Indonesia that took place in the mid-to late 1960s in which somewhere between 500 000 and 1 000 000 people (mainly leftists) were slaughtered by the Suharto military regime and then there was Whitlam’s ‘nod and wink’ to Indonesia in 1975 to invade East Timor. Of course Malcolm Fraser and his government went along with that crime against humanity. And so it goes …..

The Lying Nasty Party Coalition has Australia marching off lock step into further US military adventures, nothing learnt from history… from The Viet Nam Farrago, into The Afghan Imbroglio, the The Iraq Fiasco which clearly led to The Da’esh Disaster spreading outwards.

“Die Geschichte hat noch nie etwas anderes gelehrt, als dass die Menschen nichts aus ihr gelernt haben.”.

Georg Frederich Hegel

History has never taught anything other than that people have learned nothing from it:

and even more apposite now…

“Er hat vergessen, hinzuzufügen: das eine Mal als Tragödie, das andere Mal als Farce.”

Karl Marx

He, (Hegel,) forgot to add this: first as tragedy, second as farce:

There were soldiers from here in the Sudan in 1860 something. And ever since.

It’s easier to give a fair go by parceling out stolen land. The US was able to do that in the western states.

It is tragic that we can’t have a Senate enquiry about the role and powers, the misuse thereof, of our so-called intelligence services. It is painfully obvious that they are ideologically compromised, and over-protected from accountability. They are clearly a state within the State with undeserved immunity. Just as so many of the police attracted to join the ‘force’ seem to be the least socially intelligent component of our society, so too does our intelligence service seem to attract the least culturally and ideologically sophisticated recruits. Like the oxymoronic ‘military intelligence’.

Pure as driven snow, we are. Not effin’ likely.

‘The AAT’s decision means the full extent of Western involvement in Pinochet’s coup remains hidden. When democratic socialist Salvador Allende was elected president in 1970, the Nixon administration began a campaign to “make the economy scream”, destablising the country with the help of allies to create the conditions for a military coup which the White House hoped would purge any potential leftist influence in Latin America…The Pinochet regime would go on to murder, torture and “disappear” thousands…’

This is what an Australian government and security agencies permitted for reasons of polity and economics. The saddest thing is that 1973 puts it on Whitlam’s watch.

Yes, but they got him in 75 with the CIA mole Kerr and his adviser Barwick. He must have been like a cat on a hot tin roof lasting as long as he did. How much could he push through before they got him?

Pick one’s fights to maximize the achievements.

Bur this activity was initiated by another Lying Nasty Party Coalition!

“Australia wants to be seen by the US to keep its secrets”

Unless it is to salvage the reputation of a discredited PM then a US National Security Council dossier is leaked.

Is the decision to suppress the documents at all indicative of the effectiveness of the Liberal Party’s policy of stuffing the AAT with their partisan hacks, failures and rejects?

That’s a tough question – I’ll hazard… YES!.