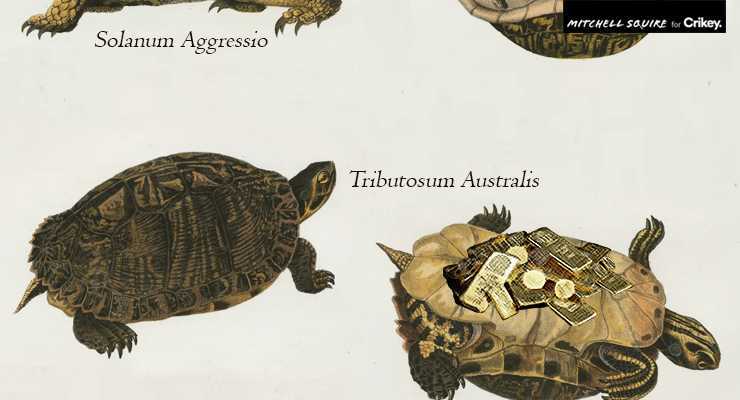

In his address to the National Press Club on Friday, Defence Minister Peter Dutton warned that China sees Australia as a “tributary state”. It doesn’t wish to occupy us, he said, but rather wanted us to “refrain from making sovereign decisions and acting in [our] self-interest”.

His\\Dutton’s point is an important one: today’s imperialism doesn’t involve direct occupation but rather “a relationship, formal or informal, in which one state controls the effective political sovereignty of others”.

A tributary state subordinates its sovereignty to an imperial state. It makes its resources available to the imperial power in the manner desired by that power’s dominant corporations. The distinction is captured in modern economics by the concept of economic complexity. Complexity increases with a country’s level of diversification (the number of products it exports), and decreases with ubiquity (the number of countries exporting the same product). A country’s level of economic development is associated with the complexity of its economy.

Australia has the lowest complexity of all the OECD countries: we ranked 86th out of 133 for which data are available, and are comparable to Uzbekistan, Paraguay, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Albania and Oman.

Our main exports remain highly specialised in iron ore, coal briquettes, gold, petroleum gas and wheat. Three years ago David Turvey, then acting chief economist in the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, wrote that “Australia’s economic complexity is an anomaly among advanced economies, with the economic complexity closer to that of a developing country”.

This anomaly reflects the dependency inherent in our role as a junior partner in the British empire — an earlier rules-based international order, to adopt a term of contemporary cultural management. British investment fostered vertical economic ties with London more than horizontal economic ties integrating the economies of the six colonies. That was a tributary arrangement.

We remain a tributary state but to a different imperial power. US-based investors are the biggest owners of 16 of the top 20 companies on the Australian stock exchange. As owners of the equity, they determine the corporations’ priorities and practices. US-based investors own more than two-thirds of BHP, the largest company on the ASX. They also own two-thirds of Rio Tinto, the second largest company, and two-thirds of Woodside, Australia’s largest stand-alone oil and gas company.

The only mining company on the ASX that isn’t US majority-owned is Fortescue Metals, in which Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest holds a 29.8% stake through the closely held Minderoo Group. He is also, unsurprisingly, one of the few members of his tiny class to deviate from the new cold war rhetoric.

The 20th century cold war was between two opposing and mutually incompatible economic systems with military postures that provided continually escalating threats. The new cold war is a technological competition between two state-capitalist economies linked by global value chains and technological standards.

The contest will play out across the global semiconductor industry, 5G networks, artificial intelligence, robotics, gene editing, data flows, autonomous vehicles and rare earths. Australia is rich in critical minerals essential for the technological future.

Geoscience Australia’s 2013 study found that Australia is rich in antimony, beryllium, bismuth, chromium, cobalt, copper, graphite, helium, indium, lithium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, niobium, platinum-group elements, rare-earth elements, tantalum, thorium, tin, titanium, tungsten and zirconium. Some of these are considered most critical by the European Union, Japan, South Korea, the UK and the US.

If we don’t want to be a tributary state, we should assert our sovereignty over these strategically important minerals. We should establish a nationally owned company that exercises ownership and control. We can then increase domestic innovation and support higher value-added sectors, such as high-technology research and development, advanced manufacturing and energy efficiency. We can increase economic complexity by diversifying our exports into higher value-added sectors.

We can then welcome foreign investment proposals from the US or China or others, provided they allow technology transfer to Australia, local equity participation and training. Otherwise we will continue to be a tributary state, selling the minerals to others who will sell the electric cars and other advanced products back to us.

Technology transfer policies require boldness, imagination and resolute economic nationalism. We should reject being a tributary state — regardless of the identity of the imperial power.

Yes, Australia should reject being a tributary State, however, I think that ‘horse has well and truely bolted’. As the article makes clear, economically Australia is a tributary State of the USA. In defence and security matters, Australia is a tributary State of the USA. In cultural terms, Australia is a tributary State of the USA. What’s left to give over? Not much, I would suggest. Oh, no, that’s right, you still have the lives of young men, women and citizens of all types to offer up in fealty to the great country, because old ‘war drummers’ like Peter et al., never fight, they just bang the drum.

Pretty much, cannon fodder is another of our exports. We have moved a long way from where such national ideas could even be contemplated, under Whitlam and Connor. Keating’s super scheme was another attempt to wrest some investment control back, that’s a reason the Libs in particular hate it.

in the 80s there was a book whose title struck a short note in the discourse. From memory it was called Australia and Argentina, parallel paths? The thesis and at the time, puzzle, was that, given its economy, why wasn’t Australia more like Argentina. Casual racism suggested because we were a white civilisation. I was studying economic geography at the time and a more plausible explanation was we had a history of a strong Labour movement that fought for and won good wages and working conditions and was a foundational bedrock for democracy. That in turn kept economic complexity in play, scared the Tories into mild social reform and kept a better share of capital in the country than Argentina managed.

That Labour movement has been steadily attacked and dismantled for over 20 years and we can see the results. More and more bits of Australia have become “third world” with other parts of the increasingly divided society reaping benefits from the hollowing out. It will require great vision and a radical social shift to turn this around. I suspect catastrophic climate change is more likely to arrive first.

Yes Yes Yes…

Can do crony capitalism at its best

The apparent desire to mess with this “natural order” was what marked the Whitlam government for termination with extreme prejudice. Borrowing money from someone other than the UK or USA to make investments in the mineral abundance of Australia? Terrible idea apparently. This is why our minerals are developed with foreign capital and most of the profits go offshore. Meanwhile the trillions of dollars of investment capital within Australia is mostly pumped into the already over-inflated real estate market – a completely unproductive area.

You could add cultural control to political and economic.

Yes. It’s why the Australian politicians who are pro-US imperial order call themselves The Wolverines after a 1980s US movie. They reflexively identify Australian interests and self image with US pop culture. I’ll write more about this next year.