Call it the Morrison paradox. Perhaps the least substantial three-year PM is suddenly among the most written about, with three book-length portraits and a handful of dedicated long-form essays all trying to get at the one big question: just who is this bloke?

It’s books like these that shape the accepted narrative. Chewing through them on the trot leads to a simple takeaway: he believes in nothing much, doesn’t know how to get there, and doesn’t really care. That’s the conclusion his biographers leave us.

They’re some of Australia’s best political writers with an inherent belief in the value of a political life. They’re eager to dissect his 20-odd years in politics for an inner core that explains his political success — and with a hefty side-bet in case he wins the next election.

“Transactional” Katharine Murphy found in her 2020 Quarterly Essay, The End of Certainty. “Pragmatic” says Annika Smethurst in September’s The Accidental Prime Minister. In their February 2021 take How Good is Scott Morrison?, Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen determined it’s an unlimited pragmatism leavened with “assertive stubbornness” and blame-shifting.

Nothing wrong with that. “Transactional”, “pragmatic”, “stubborn”, “blame-shifting”: in the craft of politics, these are all means to a higher end. But in Morrison’s hands they’re all means, no end.

Smethurst quotes “someone who has known him for more than two decades” describing him as a “person who doesn’t have any sort of strong values” (other than same-sex marriage). For Errington and van Onselen: “While there are question marks about what Morrison stands for ideologically, he has revealed himself to be a proponent of the culture wars.”

Culture wars, too, are means in his hands… for “old-fashioned strangulation of institutions perceived as hostile to the Liberal Party” like the ABC and universities, according to Errington and van Onselen.

Freedom from values (and factional alignment) explains why, in Smethurst’s view, Morrison has been such a destructive force in the Liberal Party’s leadership wars. In the succession of tight votes, Morrison was consistent as both urger and and vote-shifter — from Turnbull to Abbott to Turnbull to Morrison — leveraging his flexibility to move up the frontbench.

In place of values lies polling. “Almost everyone who has worked alongside him, in tourism or politics,” writes Smethurst, ”speaks of his unrelenting hunger for polling and research.”

Smethurst’s book is based on the traditionally journalistic in-depth interviews, digging back into a past that’s “extraordinary in its mediocrity”. Here’s what’s not there: any intellectual introspection, curiosity or growth. He joins the Liberal Party because then-boss Bruce Baird asks him too. He defects from his childhood Uniting Church-Presbyterianism to the theologically conservative Christian Brethren because his then-girlfriend does.

Murphy’s essay centres on the early COVID response. Errington and van Onselen detail the first 30 months of the prime ministership. Both were written when Morrison “had grown into the job” off the pandemic, cancelling out the post-election dog-catches-car confusion (per Errington/van Onselen), the Hawaii holiday, and the “I don’t hold a hose, mate” of the bushfires.

Growing? Maybe. A constant theme: events happen around Morrison. He’s an observer — commenting, not shaping.

The growth narrative was struck amidships by the reporting on sexual harassment and assault in the federal Parliament, after the earlier books were published. It exposed a concealed Morrison weakness: women. Seemed he just didn’t get it. Worse, Smethurst writes in her most powerful chapter, it revealed an inner truth that women he worked with “felt excluded, overlooked and even ignored”. (Julia Banks’ midyear memoir, Power Play, suggested the same — as did last week’s call-in of Liberal MP Bridget Archer.)

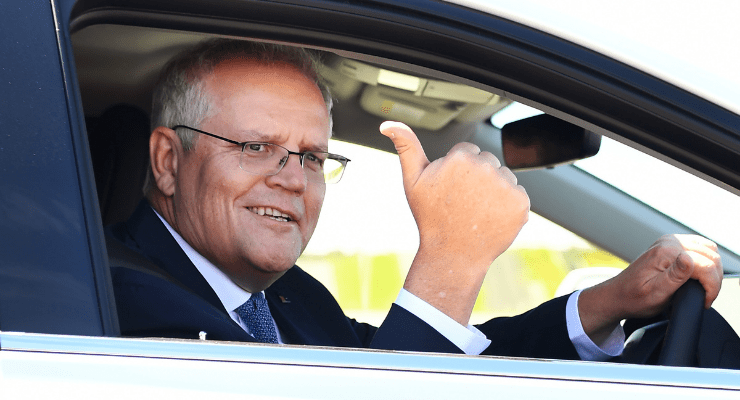

The most recent book, Sean Kelly’s The Game, eschews the hunt for the inner-Morrison that powers the hero’s narrative arc. Instead it’s the medium as the message, tracing the evolving image from tourism’s marketing boy-genius, the briefly nuanced “Modern Liberal” of his maiden speech, onto the “I stopped these” hard man of immigration, before settling on the Daggy Dad from the Shire.

Kelly’s take is that Morrison fools us all by changing his clothes in plain sight, all but admitting to constructing his nick-name taking, curry-cooking, church-going, footy-following persona — perhaps not out of whole cloth, but out of odd scrips and scraps lying around.

Not that it matters. Morrison understands that for his suburban market, as Oscar Wilde says, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Same with his word-salad press conferences and speeches — there’s always something in there for everyone. (Kelly’s book is usefully paired with Lech Blaine’s Top Blokes which looks at the onlookers to demonstrate how the target audience reacts to the act.)

There’s a danger for Morrison in these too-close searches for his inner self. Meshed together they set Australia’s political narrative, turning passing commentary into accepted wisdom. Once set, it’s hard to shift. And right now, it’s setting against him.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.