Under the traditional Canberra model of public policy, the issue of the impact of reopening the economy on the workforce and supply chains would have been dealt with something like this.

Once national cabinet had agreed on a reopening plan driven by vaccination rates, with modelling showing a big rise in infections but not of hospitalisations and deaths, Scott Morrison and the department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) would have coordinated an existing, or new if necessary, inter-departmental committee to assess the likely impacts of a sharp rise in infections, not merely on the workforce but on education, on health care and on supply chains.

Departments like Infrastructure, Health, Industry, Home Affairs and Workplace Relations would have been involved. Industry and perhaps unions would have been consulted. This would have led to a briefing on expected impacts and solutions.

National cabinet could then consider what planning needed to be done jointly, and it would become the basis for a submission to Scott Morrison’s own cabinet on what Commonwealth actions were required in those areas where it had direct responsibility — primary health care, aged care, logistics, border control, industrial relations. Ministers could have had a clear basis on which to make decisions about, for example, what to do if large numbers of workers in key sectors called in sick in the context of a reopening economy.

Pretty simple stuff. But it didn’t happen, or if it did, Morrison and his cabinet ignored it. Industry and health providers were actually ahead of the government: the Australian Medical Association warned Health of the need for a strategy to secure supplies of rapid antigen tests in September, only to be rebuffed by bureaucrats who claimed the government didn’t want to intervene in the market.

The latter comment serves to confirm that Alan Kohler’s argument that neoliberalism has enfeebled government by crippling its capacity and willingness to intervene has much going for it. At Crikey we’ve made similar arguments about the vaccine rollout and in other areas such as the NBN.

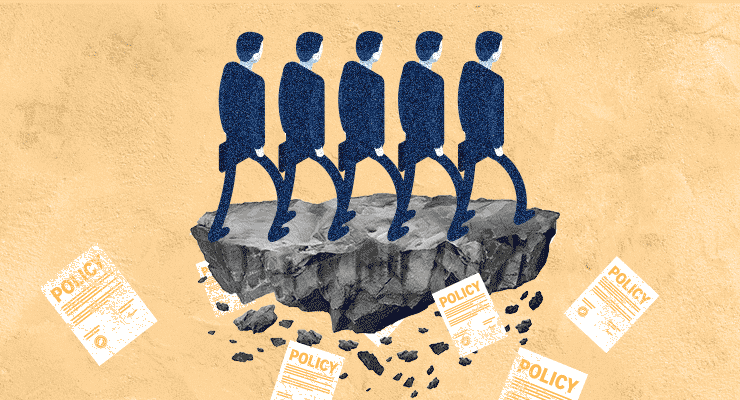

But it’s also the case that government no longer functions in the way it used to. Its capacity, its motivations and its leadership have all changed, in ways that have undermined its capacity to act effectively, even in the event it wishes to do so.

The capacity of government has diminished. Federal MPs are now drawn from a less diverse range of backgrounds than 30 years ago. Between 40% and 50% of MPs in the current federal Parliament, depending on the party, are former political staffers; the remainder consist largely of lawyers and bankers.

The dominance of former staffers affects both the life and professional experience of MPs (and the ministers drawn from their ranks), and the role of political staff. The job is no longer about providing high quality political advice to ministers — it’s simply a stepping stone into Parliament for junior party workers.

This has coincided, under the current government, with an unusually poor-quality ministry with virtually no strong performers other than Ken Wyatt, who is working in his area of professional expertise.

The capacity of the public service (APS) has been, by common agreement, significantly diminished. Many of its function have been handed to political donors, either via outsourcing to large consulting firms, or through corporate executives directly writing government policy. And decision-making has been shifted increasingly to ministers’ offices and their staff, who operate with virtually no public accountability and thus have less incentive to ensure good process and sound reasoning.

As a consequence, high-quality public servants have decamped or been sacked for being too independent. The current generation of public service executives is the weakest in living memory, with few strong performers. And the most experienced secretary — Home Affairs’ Mike Pezzullo — presides over the most disastrously incompetent department of all.

The motivations of government are now quite different, and not merely because of Scott Morrison’s obsession with announcements over substance. As John Daley argued in his outstanding final report for the Grattan Institute, the transition of political staffing roles to career ladder changes the motivations of staffers to minimising political damage, not producing good policy. And the motivations of senior public servants are no longer the much-vaunted “frank and fearless advice” but, increasingly, aiming only to minimise embarrassment for the government. Public servants by now know that undertaking planning or policy work that may result in embarrassment for the government far outweighs any benefits that might flow from it, and act accordingly.

The leadership of both the public service and the government is also at a nadir. The APS is led by a political apparatchik, Phil Gaetjens, who operates as Scott Morrison’s personal fixer rather than the leader of the Australia’s premier public policy institution. The Coalition has, by widespread agreement, persistently acted to politicise the public service. This could partly be offset if the Prime Minister’s Office was a strong policy unit, but it’s the poorest we’ve seen in decades — worse than Tony Abbott’s or that of the last years of Howard.

Above all, Scott Morrison himself has deliberately crippled the public service by explicitly ordering it to abandon any goal of providing policy advice — in the “Morrison Doctrine” of the APS, it exists purely to carry out the wishes of the government. It is not the APS’ role to undertake planning, unless the government explicitly asks for such. All policy must be determined purely by politicians and their staffers.

The result is a government machine that — even before any ideological overlay of “small government” or “let the market decide” — lacks capacity to anticipate or think through even moderately complex policy challenges, has no motivation or incentive to do so, and is actively discouraged by its leadership from doing anything other than maximising partisan outcomes for the government.

How much of this would be remedied by a new PM or new government? A change of PM can do much: Malcolm Turnbull was interested in building a better, more effective and more competent public service — a task simply abandoned by his successor — and in innovation, digital transformation and, generally, good ideas in the public sector. He returned the sacked treasury secretary Martin Parkinson to head PM&C.

At the same time, outsourcing, driven by strong fiscal discipline, continued on his watch, eating away at the entrails of the APS. That damage has accelerated under Morrison, and will take a decade to repair, if anyone is interested in the task. The skewing of public policy by the growth of political staffers is also unlikely to change any time soon.

There’s an example of what all this could mean in the long term. When Labor returned to power in 2007 and decided to take an activist approach to broadband infrastructure, it had to rebuild the Commonwealth’s communications infrastructure delivery capacity from the ground up, because that capacity had been corporatised, then privatised, under previous governments of both sides. The rebuilding delayed the NBN rollout and left it vulnerable to a change of government. The result more than a decade later is an unsatisfactory, wildly over-budget compromise infrastructure.

Once capacity and competence is lost, it can be very hard to get back.

I believe the piece is correct in every way, I believe Howard was the worse thing to happen to Australia and his ideas are still been use today in the LNP government

Pretty much everything wrong with Australia is a Howard legacy. Rudd-Gillard made too little effort to cancel his nasty policies. Similarly, don’t expect an Albanese Government to walk back Morrison’s toxic legacy.

Unfortunately Labor was in for only six years until male hubris and egotism destroyed the opportunity of healing Howardism. In spite of this lots positive was achieved and good leadership through the GFC

Then you blame Labor…… Sustainable Population Australia SPA has been central in helping the LNP, fossil fuels, IC auto, mining etc. to avoid sensible policy constraints by deflecting to the Anglosphere’s confected environmental obsessions about refugees, ‘immigration’, NOM and population growth in right wing legacy media.

Interestingly enough, this is related to the right wing nativist Tanton Network (promoter of the ‘great replacement’, muse of Steve Bannon and like colleague of Paul Ehrlich at fossil fuels supported ZPG presented as ‘progressive’) has much support and influence amongst ageing Labor and Greens, including retired Labor MPs.

Meanwhile anecdotally, a student (recent German immigrant) said of SPA that it claims to be an environmental NGO but all it does is complain about and denigrate ‘immigrants’ (worse, post 1970s immigrants); masking a strong return of old white Australia sentiments to underpin political PR targeting above median age voters.

“Anecdotally” seems to sum up your comment perfectly.

Not anecdotal nor has been the behaviour of some SPA types, for over a decade now, when confronted with grounded facts and analysis that do not gel with their Malthusian ‘beliefs’ masquerading as ‘science’ or ‘demography’.

This includes one being ridiculed, abused, defamed, libelled and even ‘doxxed’ by two key figures, desperate to protect their ‘environmental’ PR message masking deep seated eugenics from the the 19C.

Most recent incident was a year ago when The Conversation UK was compelled to remove a defamatory comment directed at me, by a former senior SPA type, simply a lie; according to the TC UK that could have been the basis of legal action.

Stephen I feel succinctly sums up what many folks feel on both sides of the isle. Chances of a charismatic leader turning up is very slim. Blu rinse lot are a bloody disgrace. The senior labour folks need to ditch the tired elders and promote the fluent younger stand outs give blu lot a real race to scare the poop out if them. Suggest Jim Chalmers a real talent, younger & good communicator. Drop Wong too left for most, a good operator doesn’t project empathy.

LNP suggest take lucrative contract cleaning nuc reators they all have $$s never earned & private health insurance therefore little drain on public purse.

And no rescinding defence contracts. Always a socialist bugbear.

The little racist piece of crap also destroyed the party hear and soul.

Yup Howard changed the PSA in 1998. Public servants had to serve the government of the day and not the Australian public. The public service became politicised as a consequence. Howard has a lot to answer for. He should be thrown in jail.

Morrison’s “new approach” and alternative role for the bureaucracy might hav e a chance of delivering were it not for the fact that Morrison himself is the problem. He has no leadership skills – for those of us that have been in business roles for years, we know what a leader looks like and Bargearse has none of those qualities. I don’t mean he has some – I absolutely mean NONE. This twerp has so many behavioural peccadilloes, not the least being his total lack of empathy and his pathological abhorrence of any form of accountability, that his mediocre intellect can’t stop him being a failure. Were he an individual with drive, vision and high intellect, his “model” might have a chance of working, but he has none of those things, beyond a drive to be re-elected. This is a fool who has, somehow, talked his way into a succession of well-paid roles and failed in every one of them. And yet with each failure, which he of course is able to simply put behind him with nary a shred of guilt or any hint of self-review, he blags his way into a more important role – a staggering example of failing upwards, until he gets to a job where he basically can’t hide his incompetence any longer. Mind you, he still manages to retain support from many who have rationalised that “Albanese wouldn’t do any better” – something which can’t be known and in part it is the case that any progressive politician who dares to challenge a conservative incumbent will, as happened to Bill Shorten, be publicly crucified, so Albanese is doing as I would be inclined to do – be a small target and try to chip away at the refusal of millions to accept that the PM Is a lying fool. If the axiom “Oppositions don’t win elections, Governments lose them” has more than a kernel of truth, by no logical assessment should the Coalition be capable of being re-elected. A more traditional public service might be ideal for someone as incapable as Promo if he were mature enough to work with a capable public service, but he isn’t and, on top of that, but he manifestly incapable of taking advice from anyone – he only needs Gaetjens as part of his machinery of cover-ups and obfuscations. Worse, he is the epitome of someone who “recruits in their own image” and another of his peccadilloes is his rejection of any ideology other than his own (he so fervently adopted Pentecostalism because it is a faith that affirms his ideological ugliness), so his neurotic impulses drive him to surround himself with evangelical Christians – who now dominate the Cabinet.

Currently reading “The Invisible Bridge – the fall of Nixon and the rise of Reagan” by Rick Perlstein, which I can highly recommend. Chapter 17, “Star” deals with Reagan’s years of mediocrity and failures in Hollywood and how he was drawn to politics because a) it offered steadier employment; and b) his gift of the gab (which earned him the sobriquet of “The Great Communicator”). While Morrison’s career is not a repeat of Reagan’s, to paraphrase Mark Twain’s comment on history, it does rhyme.

Chapter 18 “Governing” deals with his time as Governor of California, where he exploited his unbridled capacity for fabricating facts, lying blithely, deflecting questions, making false accusations about opponents, denying failures and turning defeats (eg legislative) into victories – ie telling the people he was giving them what they wanted.

The book contains a quote from Krushchev advising Nixon: “If the people believe there’s an imaginary river out there, you don’t tell them there’s no river there. You build an imaginary bridge over the imaginary river”.

“… unbridled capacity for fabricating facts, lying blithely, deflecting questions, making false accusations about opponents, denying failures and turning defeats (eg legislative) into victories …” and there we have the game plan of the Right.

‘his mediocre intellect’

That’s being kind!

Take the ‘sir’ out of Morrison and what do you have? Moron.

But great post, Iftl.

I want to up-vote this comment because of the lovely detailed put-down of Morrison himself, but can’t without some elaboration and justification for that first statement. Just *how*, under any circumstances, could the politically-driven, fully-outsourced “model” of the bureacracy ever have a chance of delivering good outcomes for Australia? How do you maintain a core of domain competence sufficient to even manage the contracting process without the progression from service delivery? Can you cite a single country that you would hold up as a good example of the “new approach”?

I don’t see any way to align service delivery motivations with necessary skills, in any of the neoliberal models, which is precicely the point that Bernard has been making in this series.

Absolutely correct article. The loss for Australia, and its population is immense, and intergenerational.

The LNP is a closed loop, endlessly circling the cesspool – occasionally someone new is able to jump in but only because they are a replica of everyone else already in the loop. I think you’d have to call it a death spiral at this point.

All the junk operators they drag in front business councils are just the opposite of what Oz needs to keep it functional I cannot look to a rep, ( my rep is laming?)a minister, a cabinet member or the crackpot pm and think they are representing any interest other than their own that is a travesty

Excellent article. How’s all that “Private enterprise runs things more efficiently” and “I want the government out of my life” attitude coping with the current situation?