Prime Minister Scott Morrison has underestimated the power of women time and time again, and it could cost him the election.

Parliament is all about protection: protecting party members from bad press, keeping the daily dealings of politics behind closed doors, and presenting a unified front to the public.

But in following the unofficial parliamentary playbook, Morrison has underestimated the power of women who have seen too much.

The Me Too movement has given women a name to what they know has been wrong all along, garnering huge amounts of support for women coming forward with their stories of abuse, bullying and harassment. Criticism of Morrison has been mounting, with women — even from within the Coalition — calling out his poor behaviour and dodgy conversations as they arise.

Women have long been ignored on both sides of politics. In the 2019 election, just 35% of women put the Liberal Party as their first preference, compared with 45% of men. Just 15% of voters under 24 voted Liberal. Although Labor scored more of the female vote, it failed to target the Coalition on failing women and scrambled at the last minute to implement gender-based campaigning.

But women are likely to be a key focus of this year’s election.

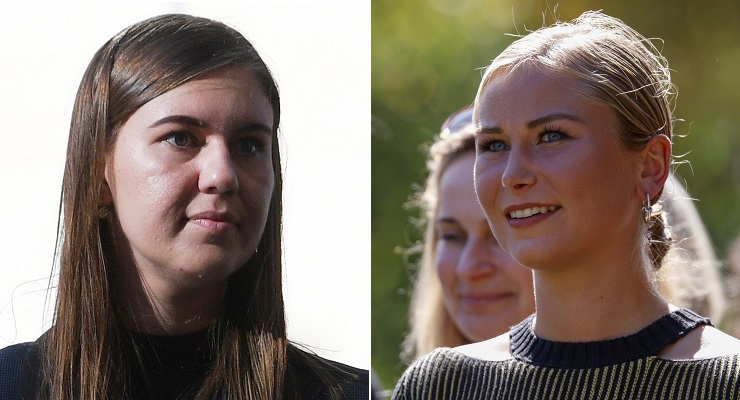

Brittany Higgins and Grace Tame wield enormous power. They’re well connected, famous and relentless in their drive for justice. Importantly, neither are affiliated with Labor or the Greens, showing the anger around the state of politics isn’t just about party preference, but about the shitty behaviour inside Parliament.

The pair also — as text messages from Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce leaked by Higgins show — have access to insider information damning to Morrison’s reign.

“I and Scott, he is Scott to me until I have to recognise his office, don’t get along. He’s a hypocrite and a liar … I have never trusted him and I dislike how he earnestly rearranges the truth to a lie,” Joyce sent to Higgins via a third party in March 2021. Joyce was on the backbench at the time.

Joyce has apologised to and been forgiven by Morrison: “People say things, and people feel things, people get angry, people get bitter.”

Bitter indeed. And Joyce wasn’t alone in his criticisms. Liberal women Julia Banks, Lucy Gichuhi, Linda Reynolds, Kelly O’Dwyer, and Julie Bishop each spoke about bullying within the party following the leadership spill. While Reynolds and O’Dwyer appear to have been placated, the rest left.

Higgins and Tame aren’t riding on the coat-tails of “victimhood” as journalist Claire Lehmann implied in The Australian, criticising “elevating narratives of female victimhood” as counterproductive.

“Angry and bitter” perhaps, but the pair have moulded their careers on not being victims but survivors relentless in their pursuit for change and justice. They, like scores of women, are sick of being told to smile, placating predators and protecting them and their livelihood with our secrets.

Tame’s stoic reception of Morrison’s and her refusal to smile, Joyce’s texts, and Higgins’ public frustrations at her allegations ignored and cast aside by the Liberal Party show one key thing: respect is earned, not given, and if respect is not there, many women are happy to speak up and speak out.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.