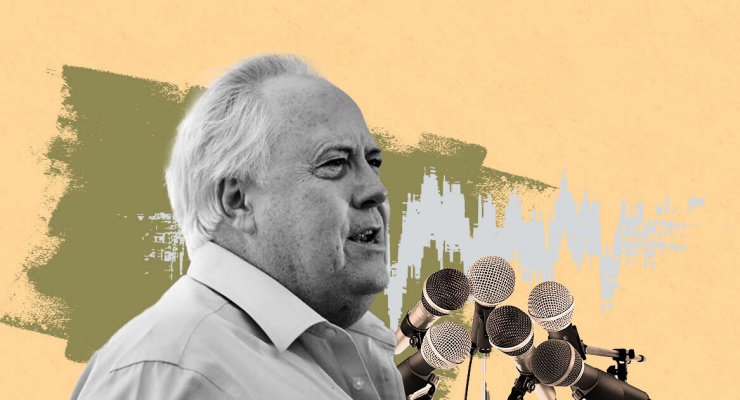

When Clive Palmer was member for Fairfax between 2013 and 2016, he attended fewer than two-thirds of sitting days, was rarely seen in his Sunshine Coast electorate and once famously fell asleep during question time.

The 2013 election first introduced Australians to politician Palmer — carpet-bombing the country with that sickly shade of yellow, twerking on talk radio and buying his way into Parliament. The Palmer United Party (PUP) even briefly had three senators.

Australians were properly introduced to “political chaos agent” Palmer in those three years. The PUP effectively collapsed as two of its senators quit. Palmer decided not to recontest a seat he was bound to lose.

The demise of the PUP didn’t end his involvement in politics. Instead he’s since leaned in hard to the political chaos agent tag which has remained a constant throughout several recent iterations of Palmer. There was “meme-lord Clive”, where the mining billionaire tried to Trumpify his image through a series of edgy (and increasingly racist) shitposts. Then there was United Australia Party (UAP) Palmer, where the yellow billboards, YouTube ads and newspaper takeovers returned with force.

There’s a through-line to Palmer’s political antics. Like former US president Donald Trump, who it’s clear he’s been trying to ape, Palmer masks a pretty standard set of rich-guy reactionary ideas behind a facade of goofiness. The goofiness helps endear him to a particular class of disengaged voter who rightly views mainstream politicians as a bunch of untrustworthy careerist dorks. And it obscures the fact that Palmer is just a very rich guy who wants very rich guy things.

It also disguises the reality that Palmer has been around politics a very long time. In the 1980s, he was a Nationals state director in Queensland, helping Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s government win elections.

A dose of old political nous coupled with an obscene, bottomless well of cash can go a long way. When the UAP’s $80 million ad blitz failed to deliver it a single seat at the 2019 election, some pundits wrote it off as a wasted investment. But the ubiquitous UAP yellow seriously dampened Labor’s primary vote in parts of NSW and Queensland, and helped cement a narrative of Bill Shorten’s shiftiness that paved Scott Morrison’s return to the Lodge.

It’s what makes the latest iteration of Palmer so worrying. Since the pandemic hit in 2020, he’s opposed COVID restrictions, vaccines and vaccine mandates, and has emerged as a vector of disinformation. He’s made former Liberal MP and conspiracy theorist Craig Kelly party leader. Despite Australia’s world-leading vaccination rates, he’s trying to tap into a muddled rump of malcontents — COVID deniers, anti-vaxxers, far-right grifters — the kind that make up the ranks of UAP’s candidate list and who descended on Canberra in their thousands.

It’s a small, vocal rabble. But in a tight election where the only constant is Palmer’s money — he’s already spending 100 times more than the major parties on advertising — the UAP vote and preference flow needs only to make a dent in a few marginal seats to be influential.

Anti-vax Palmer was meant to speak at the National Press Club today, outlining his views on the state of the Australian economy and the UAP’s financial policy. The speech was canned at the eleventh hour because Palmer was displaying “COVID-like symptoms”.

The address would have given the media a practice run at covering his bogus claims ahead of the election. Already the ABC, concerned about the spread of disinformation, had committed to a delayed broadcast.

That decision is a clear sign the latest version of Palmer is clearly the most concerning, a corrosive force on the public discourse. But it’s also Palmer at his most rogue and unpredictable.

In 2013, he wanted a presence in Parliament. He got it. In 2019, he wanted Shorten gone. He got it. This time, he and Kelly want an approach to public health most Australians have rejected. It’s unlikely his millions will change their minds on this.

But this is an unpredictable Palmer. So far he’s relentlessly attacked both sides of politics. “I get up at 2am … and spend my first hour thinking about all the nasty things I can do to the Liberal Party or the Labor Party,” he recently told The Australian.

But if he chose to turn his blowtorch on one side, he could do the damage he did in 2019. He could still get enough senators elected to create a mess of a crossbench. Even if Australians reject his message, Palmer as chaos agent will continue for at least another three years.

With Palmer and Kelly now joined at the hip

democracy’s threatened once more,

for they are the grubby and dangerous tip

of ignorance right at the core

of chaos in coming electoral fights,

a yellow-hued dinosaur force

insisting attention be paid to their “rights”…

before those of others, of course…

for here we are watching two egos on heat,

two kings of the con-artist’s game,

both experts at arrogant, bumptious deceit,

and totally lacking in shame.

But though we may laugh at these hot-air balloons

and all of the nonsense they spout,

cavorting around like a pair of buffoons

with stuff they know little about,

there’s nothing comedic about this affair,

considering where it could lead,

with millions of dollars just chucked in the air

to damage, disrupt and impede

our progress on climate change and the vaccines,

for this is how common sense dies,

destroyed by a union of craziness genes,

a barrage of dim-witted lies.

Your best yet, methinks.

This one is a keeper Gazza, brilliant as always..!!

Wow, thanks Gazza, well said.

Bang on target, Gazza. Thank you.

The line “for this is how common sense dies” could be interchangeable with “for this is how democracy dies“. Well done.

I’m not sure that he ‘wants’ anything, in the sense that he has an objective for his political activities. Back in the day he certainly did. I doubt very much that he backed Bjelke-Petersen because he was interested in his politics. But, much like the other old white rich men putting themselves out there, he is now not defined by what he wants but what he doesn’t want. And I doubt he is even very certain what it is he doesn’t want, he just knows he doesn’t like the way things are going and he’s going to use his money and old white man power to stop it. He, and others like him, are the last gasp of the privileged old white man, and they aren’t going down easily. If they have to burn the world to stop things they don’t like – gay and trans rights, workers rights, action on the environment, the rise and rise of women, non-white people taking their rightful place, action on capitalism – they will. We will eventually be rid of them, but it’s going to be a very unpleasant and probably dangerous ride on the way to their demise.

I reckon he just wants legislated carte blanche – to be able to do what he wants without consequences?

Ask the workers at Queensland Nickel what that means. He didn’t give a nickel for their interests…. it was all about him.

In business terms, he can pretty much already do that. Like Rupert Murdoch, this goes beyond business.

Clive sees Clive as number one to infinity.

Haha. Love getting downvoted by all the sad old far right white men (some of whom think they are left wing) on Crikey.

I took one of those off. I think you made good points. And these old white rich men certainly are taking us on an unpleasant and dangerous, certainly in terms of deleterious to democracy, long, last (hopefully) ride. Humankind is doomed to regress while these near neanderthals continue to blunder about.

Yep

One of Australia’s greatest threats to climate change . I hope The purhase Of AGL by a modern day thinker sinks Clive and the low grade coal within weeks and before the election .

The planet can no longer support the money at all cost, I want it now mentality

Probably a sad and old ex-lefty but I am now more an independent supporter of the new suffragettes. I have still voted you up from 4

I think there might be something funny going on with the site’s likes and dislikes – perhaps Clive trolls at work

It was clear in 2019 he needed the Coalition to further his interests in the Galilee Basin. QLD govt thought that election result instructive and waved the legislation through. Now open, and with the rail line, he is after something else from the Coalition. Stopping action on Climate change is where he is at.

To some extent. But he doesn’t have to go as full tilt as he does to do that. All he has to do is funnel funds to the LNP. He wants more than that.

Amazing how both sides of parliament have groveled before big coal .

Clive wants a government that scratches his back in return for preferences that are then called MIRACLES .

Sorry VJ, Bejelke Petersen was a relative and yes, Clive did love the power and the attention.

He never recovered from discovering his feet were made of clay and then his wings fell off.

His money landing was given to him.

Now he amuses himself and has a very Right wing agenda.

Palmer’s Waratah Coal and Mineralogy are very active in Qld. He want to mine huge coal resources and build a coal fired power station. He, just like Morrison, is a master of deceit and misinformation.

https://reneweconomy.com.au/outdated-queensland-takes-palmer-coal-plant-approval-process-away-from-council/

His adverts recently flooded into letterboxes everywhere. Many of them finished his spin full of pseudo concern for mums and dads with “God Bless Australia” so there’s a targeted influence intent. He will most probably heavily preference LNP. A climate destroyer on steroids..

These comments are all talking around the obvious point that Palmer wants the Coalition to win because he thinks they’re more likely to give him favours (tax, coal, other forms of environmental degradation). He’s completely partisan and his criticism of the Liberals is just a marketing strategy, as is the COVID denial.

But on another topic, it’s worth mentioning that his advertisements are actually good political marketing. They are bold and state their messages clearly and directly. The fact that they are bombastic and absurd makes them more memorable. As JB Hifi has demonstrated for many years, the yellow and black colour scheme is distinctive: the public associates it with a simple and no-BS attitude. During the election campaign we are almost certainly going to see bland, vague, and ultimately ineffective messaging from both major parties, especially the ALP. The major parties’ ads will look like they have been focus grouped to death and will not send any clear message to anyone. There will be frolicking multi-ethnic children at the beach and desert, middle-class families having dinner, etc. The UAP ads’ content is repugnant, as is their ubiquity, but Clive actually knows how to do electoral marketing.

Absolutely. I’m a big fan of Labor taking a leaf out of that particular foul book and bombarding social media in particular with simplistic, not necessarily truthful but scary ads.

Perfect description of the ads. from B1 & B2 to which we’ll subjected.

The yellow and black combination is used in nature to signal danger (bees etc). Not sure what CP is trying to signal.

To misquote MacBeth :

“Clive’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing. ….

Beyond the cheap seats”?

Hell hath no fury like a spoilt rich brat spurned.

All the nasty thing she can do to the Liberal Party?

After the years he and his money were welcomed by the Limited News Party – and they were happy to accommodate his interests with their legislation?

…. And where does his personal preferences settle – after the bluster?

Despite the damage he’s done Palmer accidentally delivered us Jacquie Lambie, an independent with more conscience than most in the Senate.

As the Whisperer gave us the roo-poo chucker, Ricky Muir who became a splendid Senator, sorely missed.

Let’s hope that we’ll always have Jacquie, as long as her stomach can take it.

Simple. He wants money. And he wants sh!t tins of it. The more the better. And on his own terms, without consequences for him and harm to others be blowed. And paying no tax. And borrowing to get most of it without paying any of it back. See, simple.

And you get to have a “confidential ” settlement of outstanding matters after the miracle election win .