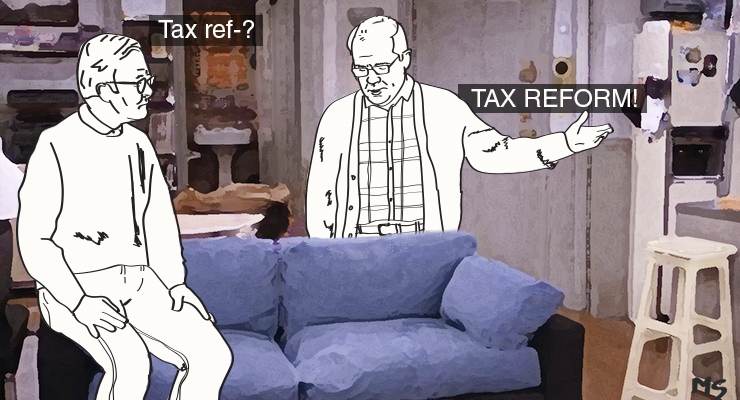

The coming federal election would be a “Seinfeld election over nothing”, economic consultant and doyen of budget commentators Chris Richardson opined last week, summing up the mood of disgruntlement among economists and the business press about the dearth of economic reform.

The Australian Financial Review has been complaining for months about the lack of political interest in tax reform. “Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese must explain why they are putting political expediency before the national interest,” the AFR whined in February. And everyone’s calling for tax reform: CPA Australia issued its manifesto; PWC — which makes hundreds of millions from enabling large corporations to dodge taxes — hilariously offered its own tax reform blueprint. The right-wing Centre for Independent Studies did the same. Tax academics have called for it. Business luminaries have called for it.

Tax reform means different things for different people, naturally. The Grattan Institute’s ideas about tax reform are very different to right-wing think tanks or business lobbyists. As Crikey has incessantly pointed out, the “tax reform” that business groups always have in mind is simply tax cuts for them and tax increases for ordinary households. That’s why, right on cue, the Australian Industry Group — lamenting how “our approach to taxation is constrained by political timidity” — issued a call for company tax cuts and a higher GST.

And you don’t need to listen to us pointing this out — even Judith Sloan has noted that “calls for tax reform, including by the Fin, are not really about making the tax system more efficient, but pleas from special interests to tax their activities less — hence the call for lower company tax rates”.

As for the Fin’s demand that Morrison and Albanese “explain” their lack of interest in tax reform, the editors of that esteemed organ have evidently forgotten it was the campaign of outlets like the Fin against Labor’s tax reform proposals in the 2019 election campaign that demonstrated why embracing serious reform is a mug’s game for any politician who actually wants to govern.

But back to Chris Richardson and his insistence that there’s nothing up for grabs at the election, because politicians aren’t interested in playing the game of Commit Political Suicide By Tax Reform.

Labor has abandoned any policy ambition, having paid the price of losing the unloseable election in 2019. But that doesn’t mean a change of government won’t mean big changes.

For a start, it could usher in a government committed to a federal ICAC, or continue in office the most corrupt government in federal history. Richardson may not think corruption is a big issue, but the billions directed by the government to its own political interests are all borrowed and will weigh on generations to come. The capture of the government by fossil fuel interests has harmed and undermined Australia’s transition to renewable energy and reduced investment, driving up costs for business and consumers.

Corruption is a growing economic problem in Australia. It also, perversely, harms the very cause that economic reform advocates back. The more voters think that governments merely govern for a few vested interests rather than in the public interest, the less likely they will back even minor reform proposals. None other than Philip Lowe made exactly this point about wage stagnation some years ago.

And wage stagnation is another area of key difference. Labor has made clear that ending wage stagnation will be a priority if it wins government — in contrast to the way in which the Coalition and Australian business have deliberately engineered a fall in wages growth over the past decade, culminating in significant real wage cuts for most workers over the past twelve months. According to RBA forecasts, workers will not see any real wages growth until 2023 and will be stuck with growth of just a quarter of a per cent — i.e. nothing after tax — until 2024.

A lack of wages growth is merely a subject of curiosity and comment for economists, high-profile consultants and editorial writers (and usually something to deplore). For them, wage stagnation is a matter to opine about, not experience; it’s what ordinary Australians get, not them. Labor, in committing to take the issue seriously, and as the nation’s biggest employer if it wins government, will be in a position to make a material difference to a country that hasn’t seen 4% wages growth since Julia Gillard and Wayne Swan were running the economy.

An election about nothing? In fact the stakes are very real, even now. For ordinary Australians, if not for elite commentators.

It is funny how business groups always think what is good for them is good for the national interest.

I recall George W Bush mentioning the ‘haves’ and the ‘have mores’ to great amusement and applause at a black tie function he was attending. Same attitude is on the loose here and the fallout will be ugly.

It’s a neocon trend these days to waste billions via private sector chaps for the benefit of private sector chaps paid for and impacting the hoi polloi without any sign of Rupert outrage . That outrage is selectively applied when an election looms however.

Good article.

Excellent article.

The moment any political party has public thoughts about serious tax reforms, they will be subject to a poisonous blast from the the evil Murdoch empire, the Nine papers and the AFR…