The founder of Australia’s biggest anti-vaccine group looks exhausted.

In a video posted to Reignite Democracy Australia’s remaining social media accounts this week, a weary Monica Smit complains to her followers about the costs of running the group and employing staff as she asks for money.

“If we don’t get more funding, we’re going to have to cut down what we can do,” she pleads.

She supposes that if 10,000 people chip in $5 a month then they’ll be okay. Later that night, a message from the account boasts that they’ve had 60 people chip in — failing quite a bit short of her goal.

Launched during the peak of Australia’s 2020 strict COVID-19 restrictions and just after the first vaccine had been approved for use, Reignite Democracy Australia has played a key role in the effort to undermine Australia’s vaccination rollout.

Despite its best efforts of creating viral medical misinformation, storming MPs’ offices and leading protests, it has been unsuccessful. Australia is one of the most vaccinated nations in the world and is emerging from the pandemic with one of the lowest death tolls. Even half of those aged five to 11 have received at least one vaccine dose, despite anti-vaccine groups having tried and failed to capitalise on parent’s natural squeamishness about young children.

Now, Reignite Democracy Australia — and the rest of Australia’s anti-vaccine movement — is showing signs that its best days are behind it.

Reignite Democracy Australia has been begging for funding through platform DonorBox and through their app RDASocial, but neither of those show how much money it’s earning. It lists its cryptocurrency wallet’s address as one way of donating to it. The wallet has received a total of US$7.35.

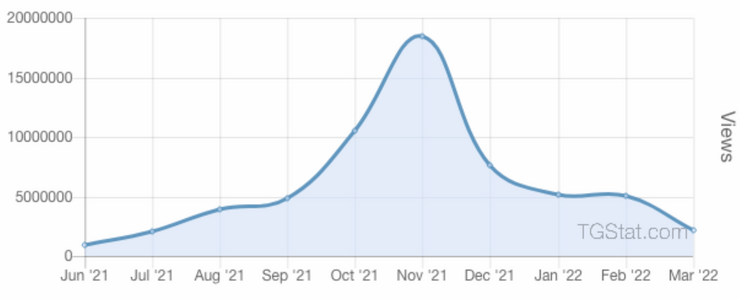

The group’s digital reach is shrinking, too. Once riding high with ballooning follower counts on platforms like Facebook and Telegram, Reignite Democracy Australia has been banned from the former and is seeing much less traction from the latter.

Recent attempts to circumvent this ban (“We’re giving Facebook another try. It’s a great way to get messages to the masses,” it wrote) have been foiled as Meta, Facebook’s parent company, removed the group from Facebook again and again.

Telegram has become the platform du jour for conspiracy groups because of its practically non-existent approach to content moderation. Reignite Democracy Australia’s channel is one of Australia’s largest, with 75,000 members. For the last month, however, its channel has been consistently losing participants. (This is unusual because active social media accounts generally tend to naturally gain subscribers over time.)

Its posts’ engagement rate by reach — a statistic that compares how many people see a post with the number of subscribers — has dropped to a third of what it was in September last year. In simple terms, its audience’s total number of people and the proportion of them who see its posts are decreasing. People are voting with their eyeballs.

A similar trend has also affected other prominent anti-vaccine voices in the so-called “freedom” movement, such as United Australia Party MP Craig Kelly, anti-lockdown activist journalist Real Rukshan, and protest organiser Harrison McLean, each of whom have seen significant slides in engagement.

Anti-vaccine movement loses steam

The peak for Australia’s anti-vaccine movement was between September and the end of last year. Events such as the Melbourne protests that kicked off outside the CFMMEU offices, the “Kill the Bill” protests against Victoria’s new pandemic bill, and the beginning of Parliament House protests each acted as lightning rods. They provided a concrete call to action, a sense of growing momentum and engaging social media content.

By the beginning of 2022, things were changing. The vast majority of Australians had been vaccinated and COVID-19 restrictions, including vaccine mandates, were being phased out. Google searches for phrases like “vaccine”, “vaccine injuries” and “vaccine mandates”, as well as Australian media mentions of “vaccines”, plummeted. Essentially, the movement ran out of things to post or protest about as almost everyone got vaccinated and got on with their lives.

They were already over the peak by the time of the Convoy to Canberra. One researcher told Crikey that she believed that part of the appeal for many of the freedom figures to make the pilgrimage to Canberra at the beginning of February was that protests had begun to die down in cities like Sydney and Melbourne. It was a last-gasp effort.

Subsequent protests in places like Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane are happening less frequently and attended by fewer people. Some of the major livestreamers like Real Rukshan have stopped attending protests. The protests were a virtuous cycle: swelling numbers became a bigger spectacle that led audiences from around the world to tune in, which in turn fed the protests.

The backslide in interest has reversed the dynamic. Smaller, monotonous protests on an increasingly irrelevant issue aren’t drawing the same audiences, which means there’s even less reason to livestream or watch for all but the diehards. Out of sight, out of mind.

The anti-vaccine movement tried its hand at electoral politics but has been unsuccessful so far. Despite a widely held mistrust in institutions, many involved have or are seeking office. In the state elections since the pandemic, no single-issue, anti-vaccine, anti-mandate candidate has been even close to being elected, nor has there been a surge in support for established parties who flirt with the movement such as Pauline Hanson’s One Nation. Several groups are jostling for the anti-vaccine vote in the upcoming federal election, but polling isn’t picking up a significant bump in their support.

The introduction of electoral politics into the movement has produced problems of its own. The United Australia Party’s open embrace of the anti-vaccine rhetoric at first was welcomed by the movement, including the formation of a partnership with Reignite Democracy Australia, but the relationship soon frayed. Telegram channels were filled with discussions about how Clive Palmer’s red shoes and Craig Kelly’s hand gestures were signs that they were puppets of the new world order. Monica Smit’s fiancé, an anti-vaccine content creator called Morgan C Jonas, publicly resigned as a candidate for the United Australia Party and chose to instead run as an independent. Schisms have emerged between those running for different parties as well as between those who wanted “political politicians” — as one Convoy to Canberra organiser said — to stay out of the movement.

The millions of dollars raised through the pandemic for legal challenges against vaccine mandates and COVID-19 restrictions have largely come to nothing. Nathan Buckley, who had created several online fundraisers for class action suits that had all been unsuccessful, has had his practising licence suspended and is running for One Nation. Australia’s longest running anti-vaxxer group, the Australian Vaccination-Risks Network, has recently raised nearly half a million dollars for a legal challenge against the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s approval of COVID-19 vaccines, which has yet to even prove it has legal standing to go ahead.

Perhaps sensing the shifting energy, major figures in the movement have also begun to focus on other issues. Pro-Russian messages about the war in Ukraine and the floods in Queensland and northern NSW, the spiritual home of Australia’s anti-vaccine movements, have taken over feeds once dedicated to vaccine misinformation. Reignite Democracy Australia is trying to pivot to focusing on the federal election by spreading lies about electoral fraud.

The consequences for those most involved in the movement continue to pile up. Rifts have opened between organisers after tens of thousands of dollars went missing in the aftermath of the Convoy to Canberra protests. Questions are being asked about the $320,000 raised for flood support by a group founded by three anti-vaxxers. Anti-vaccine business directory website Fair Business Australia’s Bec Lloyd released a video defending against claims of scamming and ripping off other people’s work. One prominent figure in the Convoy to Canberra protests was admitted to Canberra Hospital’s high-dependency unit after suffering a manic episode. Some figures like Romeo Georges or Matt Lawson who were big parts of the early movement have left completely or stepped back from personal involvement. Others are facing court for alleged crimes.

Australia’s anti-vaccine movement was gifted the perfect opportunity. Here’s what they leave behind

COVID-19 has been the perfect opportunity for the anti-vaccine movement. A low-information environment that was constantly in flux. Governments making up new, strict rules on the fly that took away rights and liberties for an invisible enemy. Social media and technology facilitated the spread of misinformation and conspiracy at a speed and scale never before experienced during a pandemic.

Even as these conditions fade, the movement’s lasting influence will be the connective tissue created between the people sucked in by lies and rumours. Australians who were tepid or unsure about vaccine safety are now hooked into networks of conspiracy and extremism via apps like Telegram. Even as their white-hot anger and fear diminishes, they remain disenfranchised and sceptical, if not outright hostile, of the government and our institutions. These dormant concerns and connections are ready to be re-activated by the right moment or person.

But those watching the movement warn against assuming that the movement will peacefully ebb into obscurity, as it was before COVID-19. ASIO chief Mike Burgess warned about violence from radicalised anti-vaccine, anti-lockdown protesters just a month ago. The Australian reported that police were expected to charge high-profile leaders of the movement for incitement to violence, although this has yet to eventuate.

Online activists and researchers who’ve been tracking Australia’s anti-vaccine movement told Crikey that a new generation of more radical anti-vaccine protesters who are steeped in sovereign citizen ideology have taken the reins of the movement. Campsites with the leftovers from February’s Convoy protests — led by people like Jim “Iron Thunderbolt” Greer and Dave “Guru” Graham — are festering just outside Canberra. Diehards have spent weeks in squalid conditions, becoming increasingly detached from mainstream society and submerged in toxic communities using violent rhetoric.

Outside the Lodge on an overcast day earlier this week, an anti-vaccine campaigner spoke on a microphone at cars whizzing past. She told a handful of other assembled activists, three sitting in the gutter while one listlessly waved a giant red ensign flag, that the Australian anti-vaccine movement had hit a wall.

“For us, I think we need to change tactics. Canberrans are not listening,” she said.

As she finished, a single person clapped.

“Monica Smit’s financé…”

ok, new word, let me guess: financé n. The target of someone who plans to marry purely for money

How are they going to fund the ground penetrating radar required to find the tunnels under the MCG where the satanic paedophiles hold their rituals?

I probably shouldn’t be laughing Shaun, but I do find your post humorous.

Sad fact Robert and shaun there are many people in this country who believe this, including some in the ultra-right media and their easily led followers. Behind much of this thinking are the harvesters of preferences for the Coalition including the fat coal miner . With Billions of dollars in coal concessions at risk, these liars will manipulate the gullible to increase their profits.

You have just given them an idea for their next GoFundMe page!

Assuming of course they can tear themselves away from telling ‘we the sheeple’ that Putin invading Ukraine is all the USAs fault, and Putin is saving those ‘in the know’ from the whole NWO/WEF/Bilderberg Group that runs the world (presumably in red shoes).

*won’t somebody think of the children?*

??

Think is just not what they do.

The anti-vaxxers who infest this site mustn’t be awake yet. Or maybe they’re seeking advice from their mates on Telegram about what to say – hint: it will involve whining ‘how dare you call people concerned about mandates and coercion ‘anti-vaxxers’.

The people involved in this movement are used to earning money for doing nothing other than being angry frothy mouthed twots. Cue the first amendment auditors in the US. These are people who get a lot of views for their nasty little videos (if you want to see them in action, please look at a youtube channel which critiques them. Don’t give them views. Have a look at Ragical for starters.). Locally a few people have tried imitating them, foremost amongst them The Aussie Cossack, Simon Boikov. I think we can expect a lot more now. Until youtube stops monetising these people, they will see it as money for jam, which it kind of is. I think they will become more violent and I think they will become more in our faces. I also think it will play out differently here than it does in the US, but it is going to be annoying.

Of course, the other problem is if they are better organised and more radical, because there will be another pandemic, and probably sooner rather than later, and they will be more ready this time. Government authorities need to learn from the past few years and be ready to counter their efforts as well as have a better idea of what to put in place to protect the community.

Oh look. All the gutless anti-vaxxers coming here and giving negative ratings, but not making a comment. How utterly pathetic and predictable.

Stick my head up in support of VJ ,we have one in our family. This is just another self-centered decision of selfish people many of whom have problems such as narcissism.

To the down voters show some guts and state your case if you have one.That you enjoy life as restrictions ease is as a result of the 90% plus of Australians who had the jab . I would suggest the old Australian term Bludger best describes many anti-vaxers are you one ?

Agree, in US aligned with the alt right in a parallel universe with Evangelical Christians and the lube of Breitbart, Fox etc., to form not just a pro (Trump) GOP voter cohort, but also a non Democrat voter cohort, encouraged not to vote (aka Bannon’s Trump strategy).

Very comprehensive article. Thanks Cam, thanks Crikey.

I suspect that another reason why the covidiots are running out of steam, is that many of them would have caught covid. Some of them would have died. Many would have had much more severe symptoms, than any of their vaccinated friends and relatives. Some would still be debilitated by long covid. Some would be still mourning those that have died. So, I think those things, may take a bit of the energy out of the campaigning of many of them.

Gotta love devolution.

unfortunately many of them have already bred so are not eligible for the Darwin awards

Inbred you mean