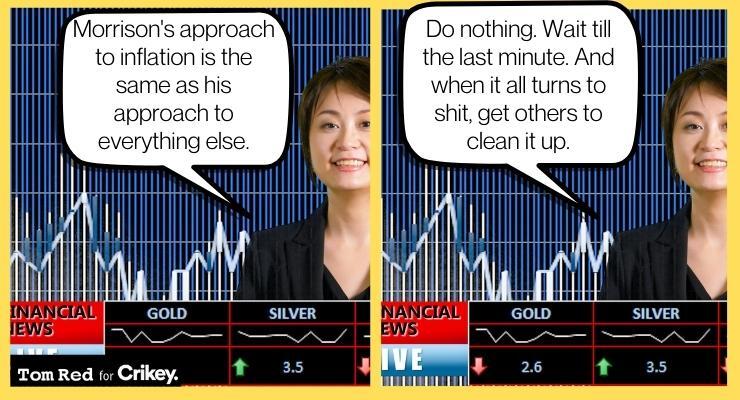

In a curious parallel to its passivity on so many other issues, the Morrison government seems to have decided to take a sideline role on the emerging problem of inflation.

As with climate policy, energy, vaccinations, aged care and other concerns, PM Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg appear to have little interest in doing anything that might look like leadership — and, if anything, are determined to make the problem worse.

That’s reflected in the budget papers, which explain how wonderfully the economy is going and how much better key economic forecasts like investment and terms of trade are going to be compared with just six months ago, but which also maintain inflation is going to rapidly fall back to within the Reserve Bank of Australia’s target band of 2-3%.

The twist: the government is pumping billions of extra spending into the economy at the same time — under the guise of “cost of living” assistance but as we all know really to encourage a jaded electorate to vote for it. To be precise, this is $5 billion more this financial year than it planned to spend last December, and $10 billion more in 2022-23 that it planned to last December.

And while the overall net fiscal position is of a lower deficit than forecast (due to higher tax revenue), the bulk of that rise in spending — via a last-gasp rise in the low- and middle-income tax offset, a $250 handout to welfare recipients and a petrol excise cut — is targeted at those with the greatest propensity to spend.

The inflation numbers are the most rubbery in the budget (“rubbery figures” of course being a term invented by Frydenberg’s Victorian Liberal predecessor as treasurer, Phillip Lynch). You don’t have an economy going as well as the government claims ours is, then throw an increase in spending, without a significant increase in the risk of inflation. But markets are now pricing in an earlier rise in interest rates by the RBA based on the expectation that the government’s election bribes will accelerate inflation and force the hand of the central bank earlier than it expected.

Remember that our current inflation is mostly imported, courtesy of surging oil and other commodity prices and global supply chain problems. But adding domestic demand on top of that could turn transitory inflation into something more permanent.

The RBA does want sustained higher inflation than we’ve had in recent years. It thinks wage rises are the way to achieve that. What it doesn’t want is domestic demand pushing inflation up above 3% on a continuing basis.

There won’t be a rate rise during the election campaign as in 2007 — when the Howard government’s reckless spending in a high-inflation environment drove the RBA to lift rates — but markets aren’t wrong in concluding the government’s spendathon over the course of 2022 will put more pressure on monetary policy.

Meanwhile others are responding to inflation as well. To cover inflation, unions want a significant rise in minimum award rates, of up to 5%, in the annual wage review being undertaken now by the Fair Work Commission. Employers, who for years have opposed every single increase in wages on the basis that they would hurt jobs growth, are now changing tack and saying employers can’t afford wage rises because of inflation.

But there’s a new-old argument doing the rounds, advanced by that friend of the workers Innes Willox of the Australian Industry Group: wage rises should be lower because of the government’s handouts in the budget.

It’s a repurposing of the deal that lay at the heart of the Hawke government’s accords with unions — that unions would temper pay rise demands in exchange for tax cuts and “social wage” reforms that had a major benefit to households — like Medicare.

Frydenberg’s handouts won’t make up for the cut in real wages that workers have suffered over the past 18 months. Moreover, those handouts are temporary, when Willox is asking workers to permanently forgo an increased wage. But Willox is right that it would reduce the pressure on inflation.

But the government doesn’t agree. It has returned to its default position of insisting wages growth is just around the corner, with wage rises set to bust through 3% next year, according to the budget. It hasn’t been above 3% since Wayne Swan was treasurer. All, of course, while inflation is falling…

The government’s position appears to be to throw some more petrol on the bonfire, then sit back and leave everyone else to deal with the result.

Inflation is like deficits. Irrelevant under a Liberal government but a national tragedy under Labor.

I reckon they are behaving as if they are a done dinner, and they can promise anything, leaving Albo to fix it up, with handicaps he doesn’t need!

And then, in Opposition, they (& Murdoch) can blame Labor. Sweet.

List of issues on which federal LNP has given leadership:

Begins

Ends.

And how do we know that petrol companies aren’t going to take this “hand-out” and whack prices up anyway?

Who’s keeping account on that “profit margin” input?

Much like “JobKeeper for unneedy businesses & millionaire donors”?

Add to that the promise of a return to pre-COVID mass immigration and the chances of meaningful wages rises are zip.

As usual Innes and his mates are being looked after.

Someone has to look after Innes and the BCoA – as well as fossil fuel companies. And, as usual, it’s us tax-payer wet-nurses, volunteered by this government, doing it.

Disagree, too easy.

There is no ‘mass immigration’ when there is a cap of around 200k p.a. including partners, kids and skilled migrants (the workforce is 13 million+).

The bigger number used is the annual temporary NOM net overseas migration churn over or net arrivals/departures of e.g. students, backpackers etc. (part time in services/hospitality) who are not working formally nor competing directly with Australians (but counted into the population while onshore).

Media presentation is wilfully confusing and used for dog whistling e.g. suggesting international students all work full time, not true, but many want to believe it…..

Net result is that any calls for improved awards and conditions are stymied by media claiming ‘immigrants are taking your jerbs’ or denying wage increases; if no ‘immigrants’ then local employees i.e. unionists are to blame….. for stopping us returning to the 19th century workplace.