There may have been a larger foreign policy failure by an Australian government than having been wrong-footed over its influence on the Solomon Islands. All we need is someone from the government willing to name it.

For by any measure this is a colossal own goal by a government that has taken every opportunity over the past two years to sheet home the looming danger to Australia from Chinese aggression in the Pacific. And it’s part of a pattern of behaviour by a government that publicly takes a dystopian view of China while lowering its guard on the real threat, as distinct from the perceived, from the world’s rising power.

Three thousand years ago, writing of the Peloponnesian Wars, the historian Thucydides described the inevitability of a rising tendency towards war when an emerging military power threatens to displace an existing hegemony. The “Thucydides Trap” has been a guiding principle of diplomacy ever since.

The economic rise of China creates a modern Thucydides Trap, one that ensnares Australia as the proxy for the world’s greatest power in the southern Pacific, China’s immediate zone of influence.

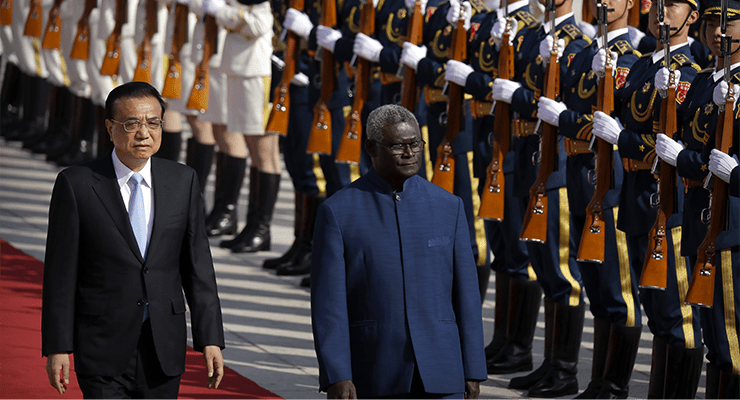

The Solomon Islands is central to this trap. Its signing of an alliance with China potentially creates a threat to Australia (although let’s not overstate it), but it also signals to our friends and foes our incapability of watching our own backyard.

This is not the only recent oversight on the watch of the Coalition government, which talks tough and has credibility on defence issues. Seven years ago, under the Coalition’s watch, the Northern Territory government controversially leased the port of Darwin to Chinese interests for 99 years. Despite the expressed concern of then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, nothing was done to trigger the national interest provisions of our foreign investment regime to stop it.

Then last year we learnt of Chinese plans to invest $200 million in a fishing port on the southern coast of Papua New Guinea, the country we should be closest to — our “little brother” since gaining Australian protection as part of World War I reparations a century ago.

China’s investment is a pittance compared with what Australia has invested in PNG over that time, but it is designed to buy influence and access to open waters in a potential future conflict. It’s also a signal that China will throw its economic weight around in a region where we have been the heavyweight.

There are many other signs. The presidential palace, foreign ministry and defence buildings in Timor-Leste, a country whose independence was due to Australian sway, was funded by China. Chinese influence is running strong through the region.

The impact of Chinese influence in our children’s use of TikTok is not well understood, and certainly not policed. So too is the impact of the hundreds of thousands of vapes — with disguised ingredients — being manufactured daily in China, many of them finding their way to our shores and schoolyards.

None of this is China’s main game. If it is going to get aggressive it will lay claim to Taiwan, maybe by 2030, or certainly by 2049 to achieve reunification by the centenary of the Revolution.

Naval power is key to this. Successful invasion of Taiwan needs China to be able to outdo American naval strength, which Taiwan would hope to enlist if faced with an invasion. The Economist reports that China’s navy now counts more ships than America’s.

“It has developed a range of anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles and sensors (known as anti-access/area-denial or a2/ad), intended to strike American and allied forces thousands of miles into the Pacific,” the magazine reports.

“The Pentagon says China’s conventional build-up is being matched by a nuclear one, with the aim of turning a minimal deterrent of a few hundred warheads into a stockpile of more than 1000 warheads by 2030 — closer to the size of America’s and Russia’s arsenals.”

This analysis supports the government’s view that Australia faces a threat at some point from China, and it certainly reinforces the need for the AUKUS alliance, which eventually (probably close to 2049) arms us with nuclear submarines.

But talk is cheap. Actions matter. And you can’t act if you’re asleep, which Australia certainly looks to have been in its responsibility to keep the Solomon Islands within our sphere of influence.

The Coalition is not wholly to blame. Labor should be mounting a much stronger argument against the Coalition’s defence record. But for Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton to use defence as one of the Coalition’s pillars for reelection is brash at the very least.

And now I hear on news.com that people are starting to call for Australia to invade the Solomons over this. How that’s supposed to work out for us I have no idea, quite apart from the moral repugnance involved

Ukraine II? Waiting for the Western Sanctions (Economic Coercion) against Australia if that occurs (but based on history no such sanctions would be applied against a White, Western country).

Why should the Coalition worry about a Chinese base in the Solomon Islands, when they (the Coalition “government” already sold them the Port of Darwin?

Operational Lease not a Sale.

100 year lease. It may as well have been sold.

A lease is not a Sale. Ownership vests with the Crown. The lease enables the Chinese owned company (not China) to manage commercial Port Operations. Even Defense have said its not an issue.

The “Chinese owned company” is owned in an indirect way by the Chinese Government so a bit like saying Chinese government is a free democratic society!

As for age Defence Dept they wouldn’t know their arse from their elbow if the Solomon Islands agreement was not known about before it was signed.

The usual nationalist Bollocks. Shandong Landbridge Group is a privately held company with headquarters in the city of Rizhao, Shandong Province, China. No more linked to the Chinese Government than Newscorpse is to the LNP despite what you read in Murdoch’s rags and no doubt watch on Sky.

As to a “free democratic society”, again its their business what type of political structure they have in place and given the size of the population in China and the popularity of their Government (with the population of China), they seem to be doing a good job. Unlike us, the vast majority of Chinese citizens that I know (and I know quite a few) have great faith in their Government. Different civilizations have different values and don’t necessarily subscribe to the view that “only the White Western way is the right way”.

The Defence Department are not part of DFAT and don’t have much of a say on foreign affairs.

This BS is just Scummo and Spudrick stirring up the usual racist feelings amongst the uneducated as part of their khaki election strategy.

“No more linked to the Chinese Government than Newscorpse is to the LNP”

So it’s its stenographer, then.

Do you even understand what I said? While Newscorpse loves the LNP there is no official link. Landbridge is just another private company just like any other company in the US.

German New Guinea “…was part of World War I reparations a century ago.”

That was what is now known as Papua, Bouganville and part of the northern Solomons.

The “...southern coast of Papua New Guinea…” where China proposed to invest $200M in a fishing port was a British protectorate/colony before & after WWI.

The rest of the island was a Dutch possession.

There is no record of the inhabitants being consulted by anybody, at anytime, during the divvying up.

It’s worth remembering that since 2014 the Port of Newcastle has been monopolised by a company half-owned by the Chinese. Another one that slipped under the radar of a Coalition government.

The nerve of Morrison & Co accusing Labor of having Chinese communist leanings & Richard Marles of being ‘the Manchurian candidate’ when successive Coalition governments have condoned transferring interest in two vital ports to the Reds. You couldn’t make this up.

I don’t think you can call them Reds these days.

Socialists, not Communists.

I was using terminology News Corp would employ.

You may care to look up how many Mines are owned by Foreign Governments. China is not even in the hunt compared to the US, UK and the Netherlands.

Let’s lump all their failings into one bucket Zut . . . Morrison Govt at large, and their understanding, acceptance of accountability, transparency, democracy distilled, reduced to one single word. “GOVERNMENT (or if you will) GOVERNANCE”.

Simply beyond his, their, comprehension?

“ So too is the impact of the hundreds of thousands of vapes — with disguised ingredients …”

Are you saying they defy chemical analysis? I haven’t come across this claim before. Links, please.

Most of the piece seemed like a cut’n’paste from other articles – nothing coherent, just a grab bag of fragments from better writers.