This is part four in a series. For the rest of the series, go here.

Two months into the Ukrainian refugee crisis, small steps have been made to address the risk of human trafficking. Ukrainians have visa rights across the European Union, meaning they can access social services and work. Police are undergoing training and organising sting operations to catch traffickers in the act, and QR codes are being placed on vehicles to help police and refugees track drivers.

But much of it seems too little, too late: Romanian authorities are attempting to locate a week’s worth of unaccompanied minors who crossed the border before social services could intervene. While police presence has ramped up, visitors to refugee centres often don’t have to produce IDs. No arrests or charges have been made against convicted criminals attempting to enter refugee hubs.

The longer the war in Ukraine drags on, the risk of human trafficking increases as refugees become more vulnerable to accepting risky offers. Experts warn that many of the protection mechanisms are bandaid solutions — and that authorities might be looking in the wrong places for traffickers.

Sting operations and police training to ‘stop the bleed’

Prosecuting human traffickers is tough — and proving “intent to traffic” is not easy, especially amid a throng of volunteers offering genuine help. Special Projects Coordinator for anti-human-trafficking organisation Unbound Global Allison Byrd tells Crikey this is where partnerships with law enforcement agencies come in.

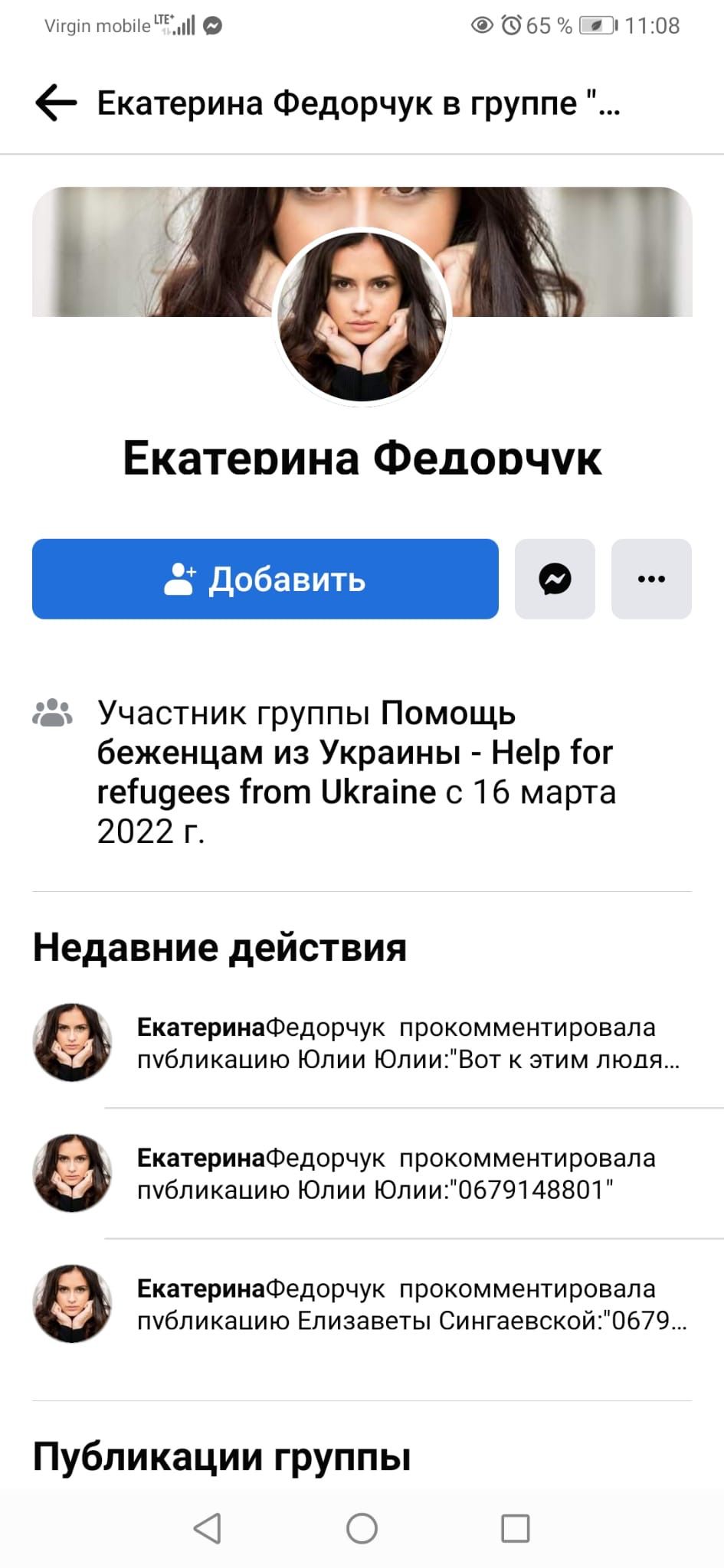

“We look out for dummy profiles on Facebook … and then you can package that intelligence in a way that it’s actionable for law enforcement,” she said. Dummy profiles are often newly set up with photos — often of women — pulled off Google. The users then post in Facebook groups offering accommodation, transport and support for refugees.

Byrd said experts could start talking to the users, looking for incriminating information — such as agreeing to paid sex with a minor — before meeting up with them. Others could pose as refugees online or in person, speaking to those at the border crossings.

But the police need specialised training to undertake these undercover assignments. Seven weeks into the refugee crisis, US-based human trafficking detective Joseph Scaramucci conducted a training session for Polish police.

“We’re teaching undercover operations and training officers what to look for,” he tells Crikey. While internet-based investigations are often more productive, Scaramucci said anything needed to be done this late in the game to deter traffickers.

“I kind of use the term like ‘stop the bleeding’ — what can we do to slow this down now?” he said.

Both Scaramucci and Byrd said they wished more had been done earlier on.

“It does seem like some of those protections, it would have been helpful to have had them earlier,” Byrd said.

“In counter-trafficking … we’re often two or three steps behind because the traffickers are highly motivated by those financial incentives.”

Tech solutions are lifesavers

Tech initiatives, from QR codes to software, offer unique protections to refugees. This is one of the few refugee crises where technology has been so widely used, mainly thanks to large companies and freelance software engineers donating their time, equipment and resources.

Telecommunication companies hand out prepaid SIM cards at every border crossing — a lifeline for families fleeing Ukraine. Separated from one another amid the chaos, with phones that don’t connect once across the border, families to keep track of one another with the free cards.

Apps also help keep track of people and identify genuine refugees and volunteers. Vlad Mystetskyi is the senior team lead at app company Monday.com. Originally from Ukraine, he worked with the company’s emergency response team to help develop the only background checking software for refugee hubs in Poland.

His system did three things: it checked people’s ID was real; produced QR codes with a summary of the registered person’s ID, contact numbers and role; and through a third-party company conducted background checks on people using Europol data.

“We pretty quickly understood and identified the main issues for the camp and started to build a solution,” he said. The system meant that when something went awry, with several refugees complaining of poor or suspicious behaviour from drivers, police had access to the driver’s licence and contact number and could act.

The software could easily be rolled out across Europe — it would take less than an hour to set up, with instruction manuals written for volunteers. So far, it’s only being used in two refugee centres, although Monday.com staff said they were in discussions with local governments.

A backlog to deal with

While the focus has been on potential Ukrainian victims, the United Nations have warned that it’s internationals with Ukrainian residents who are most at risk. Those without a Ukrainian or EU passport or permanent residency can stay just 15 days in the EU. In 2020, there were nearly half a million non-Ukrainian residents in the country. The UN has warned these people may need to be smuggled out of Ukraine, facing trafficking risks.

Services were slow to get off the ground in many areas, with refugees accepting rides from volunteers without registering with the government, with no formal mechanisms in place to protect them.

Norwegian Refugee Council crisis coordinator Przemek Rembielak believes even within the first hours of the war, traffickers were already scouting for targets. He helped coordinate transport out of regions first attacked, driving buses piled high with people out of warzones.

It was utter chaos, he said: “There were three, four thousand people crossing the border at once with some people walking 20 kilometres. Families were spread out across 50 meters. There were huge crowds and lots of buses … The snow is going down and it’s minus five below zero and people are tired. It’s so easy to make mistakes.”

With limited phone reception, he said many people were separated from one another. Kids were left on buses as parents rushed to stop a driver from moving their luggage, or kids would dash to a rare bathroom and the bus would leave without them.

“It would be so easy to grab kids,” he said. “There were children without parents because they’d lost families somewhere in the crowds, or there’d be a grandmother alone without her papers.”

But Rembielak said he believes many of those who went missing suffered a different fate. With many walking so far, some nursing injuries and as temperatures plummeted at night, he believes some people simply succumbed to the cold.

In Siret in northern Romania, a full week passed before social services were able to intervene and assist unaccompanied minors. While 512 children arrived alone between March 2-31, it’s not known how many fled during the first week of the war.

Nadia Cretuleac, executive director of children protection and social services of the Suceava region of Romania, tells Crikey they’re contacting children’s homes and local governments across the country to identify these children.

“The first week was the hardest — not just for us, but for everybody,” she said.

“All the children protection and social services from all the counties in Romania are trying to identify the [Ukrainian] children in Romania with no legal representation. We want them to be safe, we want to take care of them and for them not to be in touch with people with bad intentions — it’s our most important role at the moment.”

The agency is now conducting background checks on the people the children are supposed to meet in Romania or elsewhere.

But there is progress with plenty of police, volunteers and NGOs looking out for suspicious behaviour. Despite many services being slow to get off the ground, Byrd now believes the world is attuned to the risks.

“It’s a bad day to be a trafficker in Eastern Europe,” she said. “Everyone is watching.”

To read the rest of this series, go here.

Thank you Crikey and Amber, with these reports you have put our MSM to shame. Come home safely

For the record I have copied from LinkedIn:

About the legend :

Detective Scaramucci

began his career in law enforcement in 2004, and was promoted to Detective in 2008 with the McLennan County Sheriff’s Office, investigating Crimes Against Persons.

Since creating a Human Trafficking Unit in 2014, Detective Scaramucci has conducted sting operations resulting in the arrest of more than 550 sex buyers, and 150 individuals for human trafficking and related offenses, which lead to the identification of 260 trafficking victims.

Detective Scaramucci

has worked both state and federal investigations as a Task Force Officer with H.S.I., leading to investigations and arrests throughout the U.S. He further advises and participates in sting operations throughout Texas, the U.S. and abroad.

Detective Scaramucci

is certified in Courts of Law as a Subject Matter Expert in Human Trafficking.

He has further advised and testified in the State House and Senate, assisting with the creation and passage of laws leading to harsher penalties for human trafficking, as well as working against laws that would have added further burdens on victims.

He is further employed as a consultant, contracted to provide training and technical assistance for numerous Department of Justice-funded Enhanced Collaborative Model task forces, as well as other national and international anti-trafficking organizations.

He has trained more than 477 agencies throughout 40 states, 24 federal and DOD agencies, as well as law enforcement agencies abroad, and provides technical support for their human trafficking operations and Investigations.

{Again for the record, he is NOT the skank that Trump kicked out after 5 hours of employment.}