The most salient words from the prime minister at the Quad meeting in Tokyo came in his opening remarks: “We will act in recognition that climate change is the main economic and security challenge for the island countries of the Pacific.”

The climate emergency has always been a national security issue. As early as 2004, the Pentagon was telling the Bush administration is was a potential security risk, and it was formally classified as a threat to US national security in 2009.

It’s taken a lot longer for the penny to drop in Australia — particularly when Tony Abbott literally banned any mention of climate change in his government.

But it dropped pretty forcefully this year.

First, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine laid bare the cost of failing to rapidly dump fossil fuels from our energy mix. Households and business, especially in NSW and Queensland, face significantly higher electricity prices because of surging thermal coal prices. Australia failed to use the past decade to rapidly phase out coal from its power generation, so we’ll pay the price for years, and autocratic energy exporters like Russia — with whom the Morrison government sided on climate policy last year — will be the beneficiaries.

Our continuing reliance on fossil fuels is a “no dictator left behind” policy that makes our foreign relations environment more uncertain and empowers the likes of Putin.

And the Morrison government’s failure to prevent an agreement between China and the Solomon Islands government was in no small part due to the refusal of Morrison and co to take climate change seriously — leaving smaller island states in the Pacific to conclude that Australia preferred billions in fossil fuel export revenue to the continuing existence of those states.

Australia’s failure on climate was explicitly identified by former top intelligence official Nick Warner as a key factor in our failures in the Pacific.

Opponents of significantly stronger climate action — who remain entrenched at News Corp and in the Coalition — now have to explain why they want to undermine national security as well as our economic interests and core infrastructure.

It’s a framing of climate policy that happens to be true — and also excludes the traditional climate denialist workaround of supporting “adaptation”. No amount of adaptation is going to protect Pacific states from rising sea levels, increasing extreme weather, declining potable water and damage to the marine environment from global warming.

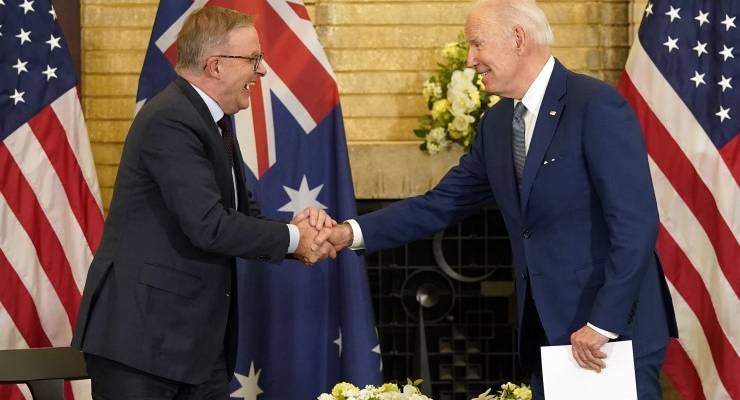

Albanese — who was attacked by News Corp journalists during his campaign as being too tired and uninterested to campaign properly — was lauded by US President Joe Biden for his energy (not necessarily the best source for praise about tiredness) and otherwise appeared to have a good summit.

He also dealt effectively with the olive twig on offer from Beijing, noting that it was Beijing that had imposed sanctions in Australian exports and that it was up to Beijing to lift them. The more interesting test will be if the Xi Jinping regime — facing a major economic slowdown courtesy of Xi’s zero-COVID policy — decides to stop shooting itself in the foot and indeed lifts some trade sanctions.

Foreign policy and international summits do little for the domestic appeal of leaders, whatever the journalists who accompany them think. But in linking what is likely to be a core domestic policy issue to national security, the prime minister has strengthened the ground for strong climate action.

Pretty good start really.

“Mr Sharma, as well as senior Liberal MPs including home affairs minister Karen Andrews, say Peter Dutton will be the next Liberal Party leader as no-one else has put up their hand for the job”.. hahaha. Who would want to lead a maggot infested hungry ghost to its grave?

“whatever the journalists who accompany them think” ahh could it be Probyn? Whe he appeared on the ABC on election night the blood had rushed from his head, he looked gravely ill . He looked like he needed to be triaged and dispatched!

What a great photo of Albo meeting with the boss.

But Albo has to do something about his “orange man” hair.

Another take on the photo… A two-handed grip, and Albo looks as if he’s saying, “Yes, I won. Ph–k, I’m relieved.” But part of looking statesmanlike is to NOT look too much the toady when in powerful company. Howard never quite got that right, and always looked—when alongside Bush—to be too pleased with himself, in a juvenile sort of way. Morrison was the same in the UK. Calm down Albo… be cool… try a single-handed shake (let the other guy do the two-hander) and just a warm smile. Congratulations, by the way.

Good take. Never let the US think that we regard them as the boss.

A lacklustre (though deep-red), not-too-bright, lightweight beta-male… and a “tired and uninterested” campaigner to boot! How come Albo made it to the Lodge? Obviously it’s time to sack the voters. If the government starts kicking goals, watch out in the run-up to the next election for a News Corp campaign questioning the integrity of the voting system and the AEC.

I have a strong suspicion Biden will remember this PM’s name.

Should be easy.