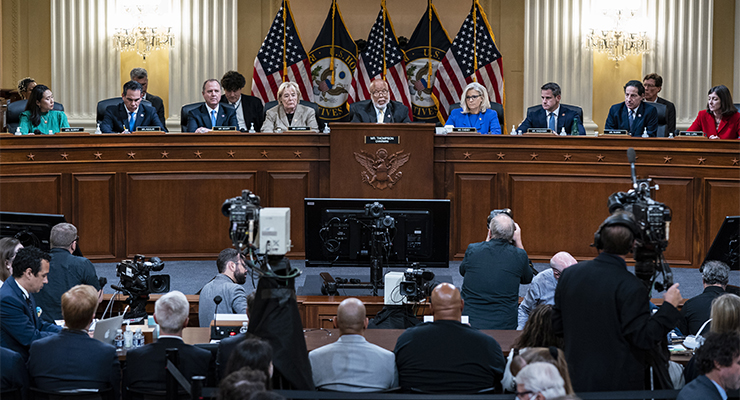

Like millions of Americans, I tuned in to watch the live coverage of the first of six presentations by what has come to be called “the 1/6 committee”. Broadcast live from 10am AEST today — 8pm Thursday night on the US east coast — the approximately two-hour hearing provided the emotional valence missing from previous attempts to hold former President Trump accountable, including, most notably, Robert Mueller’s testimony on his report surrounding Trump’s first impeachment.

Humans respond to story, and that’s what the committee provided, including displaying Trump’s tweets, visual snippets of his daughter and inner circle testifying, and never-before-seen footage of domestic terror groups executing “stacking, phalanx and flanking manoeuvres” while using the mob as a “force multiplier”.

No wonder, coupled with the sheer inadequacy of their numbers, so many capital police officers sustained injuries on the day, a point brought home by the live testimony of officer Carol Edwards, who described her experience of being threatened, overrun, knocked unconscious and tear-gassed — during which these events played out on the screen behind the committee. Behind her, her fellow officers teared up and nodded. “What I saw was a war scene … there were officers on the ground,” Edwards said. “They were bleeding and throwing up. I saw friends with blood all over their faces. I was swimming in people’s blood. I was catching people as they fell. It was carnage, it was chaos…”

The police were not the only ones struggling for composure. As images flashed on the screen of the gallows erected for Mike Pence and aggressive demands by the insurrectionists for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to be handed over to them, a collection of elected representatives at the back of the room comforted each other. It was a reminder that many of those in the room had lived through that day, or had lost a loved one during or because of it, a sacrifice acknowledged by Republican co-chair Liz Cheney when she thanked the officers for rushing into the fight as “we were rushed to safety”.

But while it was clearly important to the committee that those watching shared in the terror, disbelief and fear of those at Capitol Hill that day, its agenda was broader than this.

Firstly, it seemed designed to establish beyond doubt that the election was not stolen and that former President Trump knew it. He knew it because his senior campaign adviser had told Trump “in pretty blunt terms” soon after the election “that he was going to lose”. He knew it because he lost more than 60 court cases asserting fraud in seven states. He knew it because he was told twice by his handpicked attorney-general Bill Barr, shown twice deriding Trump’s claims of election fraud as “bullshit” and “nonsense”.

Secondly, the committee showed that Trump, despite knowing it was a lie, kept repeating his stolen election claims to a group of Americans who believed them. Cue footage of a handful of those awaiting trial or convicted of offences related to the insurrection explaining why they’d come to Washington and stormed Capitol Hill that day. “I did believe that the election was being stolen, and Trump asked for us to come,” said one. “I know why I was there because he called me there, and he laid out what was happening to the government. He laid it out,” another claimed.

So, what comes next? The committee has both minimalist and maximalist aims. At a minimum, it needs to turn enough Americans away from the #biglie that it stops being the defining issue of the Republican Party, allowing the nation to stop litigating the last election and do what it’s failed to do for the first time in the country’s almost 250 years of democracy: transfer power peacefully and move on.

Maximally, and simultaneously, the committee must show the American people its evidence indicting the former president on two federal charges: obstruction of an official proceeding, and conspiracy to defraud the United States.

For Americans like me, who long ago grasped the threat Trump posed to the survival of American democracy, the chance he could escape accountability for his crimes — and thus get another chance to finish the job — is an outrage. Yet at the same time, I understand that the country cannot risk the unprecedented step of trying a former president for crimes committed in office without the tacit consent of a preponderance of citizens.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.