Anthony Albanese’s proposed integrity commission could provide the legacy for his government for decades to come.

But Professor Peter Coaldrake’s report on political accountability in Queensland, released last week, should be bedside reading for a prime minister who wants to do politics differently.

The report offers 14 headline recommendations, but above all it shows that the tone is set from the top, and that political shenanigans are the byproduct of not placing sufficient value on integrity.

Queensland should have learnt this lesson three decades ago with former Australian judge Tony Fitzgerald’s scathing report into how the state worked — but time can dull clarity, and culture can become mired in political ambition.

Coaldrake found public servants paid a high price for providing frank and fearless advice, and that a culture had developed that allowed bullying and was dominated by short-term political thinking.

That’s a message that should travel outside Queensland. Without buy-in from politicians, and a belief that taxpayers deserve to know how decisions are made, any integrity commission will be hampered from the day it opens its doors.

What comes through in Coaldrake’s analysis is that culture and integrity are interconnected, and those institutions receiving public money to encourage accountability and transparency need to work together, not run up against each other.

His is an integrity framework, not just a series of siloed organisations responsible for a healthy accountable democracy. And at the heart of that are two cohorts of people: our politicians and the nation’s citizens.

The message for politicians is simple: try harder. Stop using departments to advance political messages. Stop using lobbyists as brokers. Stop ministerial staff from bullying those whose message might challenge their own. Protect whistleblowers properly. Be accountable.

None of that is unique to Queensland, and the recommendations he suggests could work wonders elsewhere. Making cabinet decisions (and submissions) public within 30 business days. Providing greater independence for bodies like the state auditor-general. Stopping lobbyists working on party election campaigns.

The Palaszczuk government, which has seen its popularity drop with a queue of integrity complaints, has responded quickly by saying all the right things. Late yesterday, the government moved to ban three lobbyists who had worked on her latest campaign from working with her government for the rest of the term. It has also signalled to implement all 14 recommendations, including making cabinet decisions public.

But the point of Coaldrake’s report is that laws, institutions and rules are important — but it’s the spirit with which they are embraced that makes all the difference.

The commitment is hollow if cabinet decisions are now made before reaching the cabinet room. Or if lobbyists, who identify as Labor operatives, are allowed to work with the government in the next term. Or if the government doesn’t take responsibility for the bullying and intimidation that have marked some of its dealings.

That’s the ethereal stuff. But it’s the stuff that determines whether the framework that holds an integrity commission as its altar will work.

It should be surprising that three decades after the states — first one, then the others — decided they needed an integrity body with strong legal powers, the federal government is still thinking about it. Or maybe it’s not surprising.

Over that time, there have been plenty of contentious national political issues that could have borne the treatment meted out by Queensland’s, NSW’s or Western Australia’s integrity bodies.

The overpayment for land bought for the new Sydney Airport could do with some close public scrutiny. So could the monotonous blurring between what passes for government information and advertising.

Federal Labor made the establishment of an integrity commission a core promise, and its final form can’t be less substantial than the bodies existing in the states, nor less substantial than it has publicly demanded.

Coaldrake repeatedly refers to tone from the top in writing about the issues of integrity in Queensland. In our democracy, that means the right tone from politicians whom Coaldrake doesn’t let off the hook, reminding us that responsibility for accountability ultimately sits with ministers.

Federal Labor should take careful note. Anything less than implied in its promise is definitely the wrong tone from the top.

“Political integrity” (and quoting Tony Fitzgerald) as judged by Madonna King – who used to work at Murdoch’s Brisbane Curry or Maul, selling the Limited News Party, under husband and editor Dave Fagan.

…. That’s the rag that ran PR for the Newman government – like their cheering when Campbell “One-term” Newman and A-G Bleijie legislated their bikie laws, that Chief Magistrate Tim Carmody acted as cheerleader against the rest of the judiciary that was against it.

The same rag that laid down cover-fire against anyone that criticised the Newman Limited News Party government : including Tony Fitzgerald, when he criticised their bikie laws and the hand-picking (by Newman and Bleijie) of Tim “There’s a good boy” Carmody to subsequently fill the seat of Chief Justice… “for services rendered”?

“…. The message for politicians is simple: try harder….”???

But the message from King’s old alma mater – with it’s giant swipe of our viewsmedia/PR – is “The Coalition doesn’t have to try harder”.

Why can’t King do a piece on the role of the partisan media in sponsoring this lapse in political integrity? The way they’ve covered and excused such failings in integrity from their pet side of politics : the way they’ve used their resources to go after and attack those that criticise those political failures – because it suited their political agenda?

From experience. She’s been on the frontline in that endeavour.

Now that would be interesting!

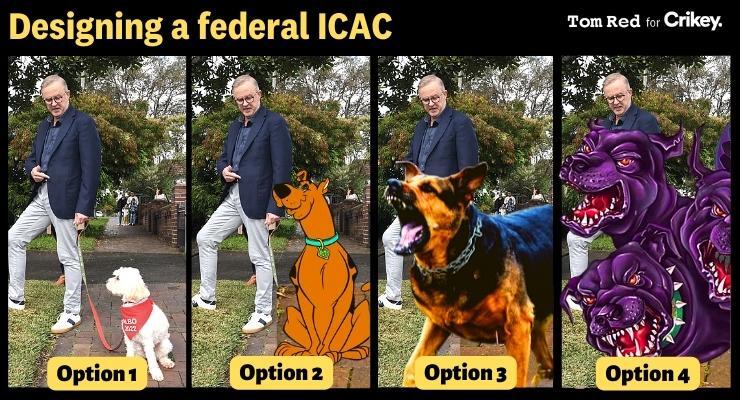

Great graphic representation by Tom of four options for a FICAC.

My vote is for option 4 and bring it on with no holds barred!

Unfortunately, Cerbeus is not an attack dog, which FICAC needs to be, but a guard at the gates of Hades to prevent the dead leaving.

For which I’d settle if it meant that we never again see the usual suspects in public life and they remained forever in the Asphodel Meadows, regretting their wicked acts.

first paragraph of the terms of reference for the Coaldrake enquiry says it all

“The Queensland public and successive Queensland state governments have been well served by its public sector ethics and integrity framework, which emphasises the commitment of both the Queensland Government and public servants to achieving high standards of professional and ethical conduct.”

The QLD gov believes all is ok

A ‘… culture of bullying (was) rife … many academic and professional staff expressed living in fear in this workplace’. One could almost be forgiven for thinking that the above was part of Professor Peter Coaldrake’s report into the Queensland Government’s integrity. But that story was reported by the Courier Mail in April 2021. The institution being referred to was The Queensland University of Technology (QUT) which had been for 15 years u under the Vice Chancellorship of Professor Peter Coaldrake.

Even though Coaldrake’s tenure as VC of QUT ended in late 2017 he was the driver of the culture referred to above. For many of the staff at QUT (of which I was one) Coaldrake ruled as a virtual autocrat – it was either Coaldrke’s way or the highway.

In 2016 Coaldrake saw the purging (discriminatory redundancy) of scores of elder ‘dud’ under-performing employees. These staff had ‘under-performed in the sense that they did not fit in with Coaldrake’s ‘vision’ for QUT. At the time Prof Coaldrake said. “QUT is quite unapologetic about its own ambitions to be recognized globally, particularly in some of the newer research fields in which we have been investing over recent years, for example robotics, biomedical engineering, health technologies.”

So appointing Coaldrake to head this review is a joke but the biggest ‘joke’ has been Coaldrake delivering a report he has titled “Let the Sunshine In’.

What a total exercise in hypocrisy. As CEO of QUT (a title that Coaldrake and his cabal of fellow university Vice Chancellor’s aspired to hold, no doubt to be seen to justify their obscener salary packages that exceeded a million dollars per year lurks and perks not included) did all in their power to hide, obscure and show absolutely no transparency in detailing where all the public money given to universities went.

It certainly was not going to the students and improving the quality of their teaching. Indeed, Coaldrake and his cabal of fellow VC.s would fight to the last just to prevent letting the ‘Sunshine in’ on their practices in running their universities.

Yes Pete sure was the right’ man for this job.