Welcome to part two of Guy Rundle’s mid-winter short course on the knowledge class. For part one, go here.

The principal objection to the notion of a knowledge class is that, well, capital still exists. Some people own the means of production, some people work for wages. There’s a categorical difference between Mike Cannon-Brookes and a jobbing coder or graphic designer, even if the latter are better paid than a shelf-stacker.

The argument from “economic classists” (they’re not all Marxists) is that the cultural divisions between non-knowledge and knowledge workers — the shelf-stacker and the waged software developer — are either confected distractions, or a degree of deflected economic class conflict.

In that latter scenario, the disturbance that many people feel at a certain sense that they are now marginal to social process is simply a diverted form of their frustration over a lack of economic power. Rather than identifying the correct enemy — capital and capitalists, who have managed to steadily raise the profit ratio for several decades — they are steered to a group of people whose representatives all seem to be doing pretty well for themselves, and who also spend a lot of time telling everyone how to live, what to believe and what to value.

The strategy derived from that is that if you just persevere with the economic class message, you will eventually persuade people to drop their superficial division — as eventually happened between Protestant and Catholic, white and black, and male and female workers.

The crucial argument from a knowledge class position is that that strategic conclusion is utterly and disastrously mistaken, and will lead to years of wasted energy and political misdirection (actually, it is). The counter-argument would be that the Marxist conclusion that “(economic) class struggle” lies at the root of other struggles fits some periods better than others, and does not fit our society very well at all.

The knowledge class seeks domination but, like all classes, it seeks domination in its own distinct way. Since its power at its root is through control of mathematics, language and cultural symbolisation, it inevitably sees the world composed in those terms.

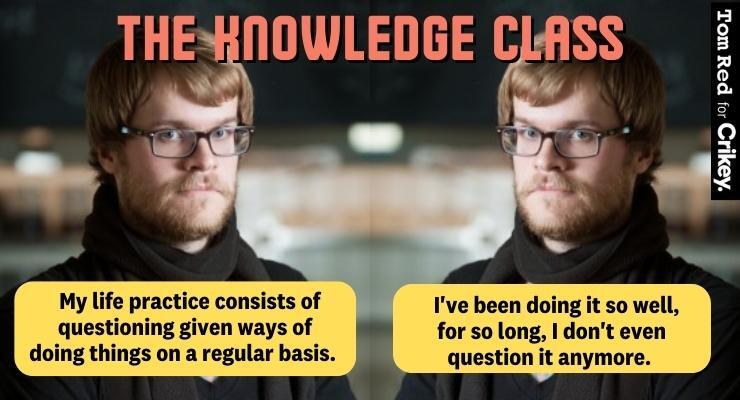

The “life practice” of the knowledge class, which differentiates it from all other classes, is to think of the world as a series of problems, institutions, and “givens” to be, to a limited degree, questioned, challenged, analysed and remade. For all other classes in all of history, life has been the opposite: a series of given and unquestioned practices and habits, partly arising from life itself and partly supplied by small external groups, such as shamans, storytellers, priests, and artists.

Once you have a whole class of people whose life practice consists of questioning given ways of doing things on a regular basis, and once this process is plugged into economic production, you get a social division that generates not only different ways of seeing the world but different ways of seeing how you see the world. From that, it generates different social-ethical objects, which strike the knowledge class as real and central — the moral centrality of the stateless refugee or the trans person are the two recent examples — and which strike everyone else as possibly true but far from central to the main business of life.

The ethical imperatives generated by the knowledge class’s way of doing things are those oriented to a radical and universal equality, a joyous breaking of any inherited forms of particularity. Thus, in any situation where the economy has not seriously collapsed, the fond hope of the economic classists — that economic class calls the shots “in the last instance” — is likely to be disappointed. At the very least, it will encounter vastly more resistance than the economic classists (which includes many Labourists) anticipate.

But why does the knowledge class have such power and cultural unity, even across the capital/labour divide? We’ll find out in part three — the grand finale!

Might not another counter argument be that the Knowledge Class is prosecuting the class war, on behalf of the capitalists? In order to forestall economic precarity and job loss to algorithms for the Knowledge Class, they function by better managing everyone else, better dividing them (by identity, say) & expanding HR speech controls from the workplace into the polis, precluding open discussion about the Knowledge Class’ idee fixes while promoting a trendy, weak anti-capitalism.

At the present time there is a surfeit of knowledge class trying to get a Tradie.There is no problem of a Tradie getting a knowledge class [ if they wanted them]

Why would they?

Useless, effete and soft handed wastes of space most of them who have never broken a sweat and are a burden on society.

I’m a knowledge sponge or perhaps knowledge junkie. Also a professional, also have calluses on my hands, also not urban and i sweat so much at work, my sweat rots leather. Tradies need engineers for shop plans and certified drawings. And they need doctors. So what are you really saying Freyja?

A nonurban professional whose sweat rots leather. I call B/S.

The only reason tradies need “…for shop plans and certified drawings” is to give the desk jockies something to do.

The sort who approved the crumbling towers of Zetland & north Sydney.

I can show you a photo of the leather rot. You could always read up on specialisation in a sophisticated society. Perhaps you prefer a cave and fire?

Gotta agree. I related this before that there was a firm of said IT Geeks which said as part of its pitch that if they couldn’t fix a problem, it’s free. Well they couldn’t and they redefined what it was that they could fix within their terms and conditions and it wasn’t free. I agree but I remember my boss in 1995 prior to my commencement with the Federal Public Service said to me about a young kid we knew on one of our jobs seeking to work out a trade to go into. Well he said that if you’re going to do a trade, you might as well sit on a beach. I remember and I was there when tradies were surplus to requirements. So were engineers. There were many of them unemployed. IT workers were coming in to their own then and were earning good money. Now the tables have turned. The tradies are largely self employed. Small businessmen or many wanting to be. Knowledge workers sound they are more diverse and not really amorphous like tradies who can still, despite the seeming simplicity of their categorizations and work type, fall into those of capital and labour. It is not sure what this knowledge class can fit into. Guy wants to put them in a class of their own but the rules of the game just don’t really allow for that,

Tell that to the Tradies whose kids don’t have a teacher

Most tradies could fund private tutors from their ‘War on Utes’ tax concessions alone.

It is government policy that this is so. Governments, schools and state industrial tribunals and courts don’t price teaching properly. Simple

I would say tradies are knowledge workers – they can do what others can’t – the knowledge required is arcane to those who employ them to the point where they don’t know now how to price it. They only know a dodgy plumber or a dodgy code developer can cause disaster. A manager can stack a shelf so they can price that work but they don’t know how to refactor code or trowel fall into a bathroom floor. This is why knowledge workers retain economic power it doesn’t matter if they use power tools or a computer. (Obviously subject to the laws of supply and demand but so is capital)

Grundle is our James I & VI – “wisest fool in Christendom”.

I dunno. Tried to see a family lawyer lately to get a divorce?

Any Marxist who hasn’t noticed the changes in the labour process over the past 150 years along with the emergence of this new class does not deserve the name of Marxist. But hey! I know. Who cares? And of course, there is no implication, is there, that the Knowledge Class somehow replaces the industrial working class or the capitalist class or that growing class of care workers – mostly female who make up the bulk of the organised working class. But while the capitalists remain the “great stumbling block” the industrial working class is no longer (as it once was) the most progressive class in society. This just makes life pleasingly a lot more complicated.

Guy, are you familiar with Pierre Bourdieu’s take on all this?

Thank you for mentioning Pierre Bourdieu, Andy. I looked him up. As a parent to teenagers, a particular interest is his explanation of how social and cultural capital is transmitted across generations.

Check out Pyotr Kropotkin for their further edification.

He is. This from footnote 9 in GR’s autumn Meanjin article:

“In recent years left groups have taken an interest in a class system arising from Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of different forms of capital, including cultural capital, with which the above argument has obvious overlaps. But Bourdieu’s classification remains one of consumption and taste circulation, and can thus be rejected as ‘sociologistic’. Of course, in a knowledge-culture economy, the production–consumption distinction breaks down, since cultural consumption is a form of production, the raw materials for the reproduction of the intellectually trained self.”

Knights in shining armour that paradoxically possibly have more Neoliberals in their grouping than… hang on there’s Neoliberals in every “class”…. tomorrow.

I need to know whether I am in or out of the knowledge class or just a comfortably off left wing sh*t stirrer within the bourgeoise. Tomorrow then!