Look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves, so the saying goes.

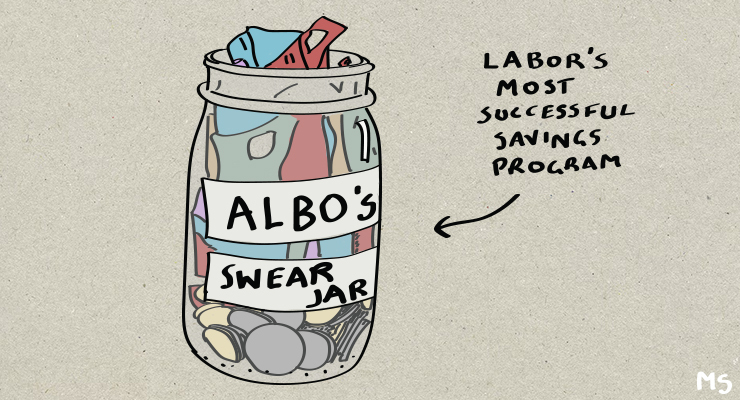

It’s a mindset Prime Minister Anthony Albanese owned in opposition, saying that growing up in a poor, single-parent household taught him scrupulousness he’d apply to government finances. Now in government, Albanese has directed his ministers to find savings in their portfolios.

But kitchen-table folk wisdom — or poverty-induced frugality — rarely translates well to public policy. Indeed, if you do too much penny-pinching you can create problems that will take pounds to clean up later.

Last week Albanese learnt that lesson the hard way.

Out for a pound

On Saturday he backed down on his planned scrapping of welfare payments for COVID isolation, agreeing with national cabinet to extend the scheme until September 30.

Albanese also reinstated telehealth appointments to administer antiviral COVID treatments, after cutting funding for 70 consultation types at the end of June. For now at least, he remains committed to scrapping free rapid antigen tests for concession card holders.

State premiers, the opposition and his own backbench saw before he did that such cuts were self-defeating. They would worsen the winter COVID wave and cost the government more in health resources and lost tax revenue than it would save.

Licking its wounds from its first embarrassing own goal, the Labor cabinet is likely to limit its fiscal restraint in the health portfolio for now. Perhaps it’ll extend the free RATs program before it lapses at the end of July.

But the frugal mindset runs deeper. The government has strained important relationships with new crossbenchers by cutting their staff allocation, saving a mere $1.5 million (chump change for a federal government). Labor also dumped relatively low-cost, likeable promises during the election campaign such as parental leave super.

And we’re warned there are more cuts to come. Why?

Spending ≠ inflation

Albanese argued recently that the Reserve Bank could see increased government spending as adding fuel to the inflationary fire and thus raise interest rates further. With costly childcare and aged care policies locked in, compensatory cuts must be made.

But not all spending is inflationary. Indeed many foreshadowed items in the October budget could help reduce inflation.

Sure the money families save on childcare could be put towards a new car or holiday, thus bidding up their already ballooning prices. But by allowing more parents (predominantly mothers) to enter the workforce, output can be increased, reducing its imbalance with demand and thus price pressure. Albanese argued earlier this year that his childcare reforms will be inflation-reducing.

Yet free RATs and isolation payments could also reduce inflation by stopping the virus from spreading among colleagues — keeping more people at work and churning out more products. Why not maintain these policies on the same grounds?

Ghost of deficits past

Beyond inflation, increasing interest rates raises the cost of servicing government debt. So looking for modest savings in wasteful or inflationary areas is sensible. For instance, Albanese has proposed cutting often-rorted community and regional grants programs.

Liberal Senator Andrew Bragg has proposed cutting federal judges’ generous pensions. There are likely to be other poorly justified items in the policy cupboard.

Then there’s tax reform. Perhaps not on the table this early in the election cycle, but it must be strongly considered eventually given how low Australia’s revenue is by global standards.

But with high commodity prices and low unemployment increasing revenue from existing taxes, a relatively manageable deficit by historical and international standards, and growth-enhancing social reforms on the way, it’s hardly time to panic and dump valuable policies.

Labor cannot afford to distract itself, the media and the public with attention-sapping spot fires for inconsequential sums, causing real harm in the process. Overplaying its hands this soon suggests paranoia. It has long been scarred by the Coalition’s baseless scare campaigns that Labor governments recklessly spend too much.

Yet by projecting stern respectability to recapitulate yesteryear’s war, Albanese risks being stuck behind the times. Australians don’t care that much about the deficit any more. Sure certain quarters of the media will undoubtedly rediscover their fiscal hawkishness now Labor is in power. But with even the opposition calling for COVID spending to be maintained, now is hardly the time to ape Scrooge.

Australians do care about living safely and practicably with the pandemic after two years of hardship and disruption. If Labor tarnishes its credibility as a steadier pair of hands on COVID, health and social services — its present electoral advantage — its bigger problem will be a deficit of trust in government.

Could always get back the money wasted on JobKeeper (aka bonus keeper) and given to the banks for free (by the RBA).

No-one believes that cutting staff to the cross bench was a cost saving – it was purely to limit its effectiveness.

A sure way to win friends & influence the very people needed to ensure decent policies – especially dumb given that the government has no idea what such things might be.

It was justified as an equitable measure. In a simple minded way, it is. If government backbenchers get so much assistance, why should other backers get any more(or less). Whether this is really equitable depends on whether all backbenchers are really equal because they are all backbenchers. It is arguable, as Labor realised by expanding staff in the parliamentary library, that they are not, since party discipline and caucus meetings simplify things for Labor backbenchers. It is hard to say what is needed to compensate for that for other, especially independent backbenchers, but it probably less than what Morrison tried to buy their goodwill.

Looked to me like Albanese is still in “small target” mindset, afraid of the LNP and Murdoch media. He needs some coaching from Paul Keating on how to be brave, and how to get others to get on the Bandwagon of the Brave.

He did a pretty good Keating in QT today

It didn’t take long – the foreign diplomacy part so far has been well received, but with anything else Labor seems to be shooting itself in the foot and they are just continuing a similar policy stance as their predecessors minus the smirk. Instead of laughing in our faces like the coalition, Labor will just laugh behind our backs. Their climate policy looks to be a lot of hot air, they are still firmly punching down on the poorest and signalling austerity. Wonderful – really hope we knock them into minority gov’t soon.

Given the government has a two seat majority, not sure how you expect us to ‘knock them into minority gov’t soon.’

Trigger some byelections, maybe? P’raps somebody stayed up late and watched a rerun of the Pelican Brief.

Scotty won’t show his face again so bye election in crook I mean cook?

Act of God or poor diet, wayward bus or somebody having an attack of ethics? One may dream.

I guess the problem is, what is your expectation for the handling of such spot fires? Albanese signalled early on that national cabinet would discuss the issue, which I understand is cofunded with the states (but happyto be corrected here). We critiqued the former government for making policy on the run, yet we have treated a couple of days of policy consideration as a major crisis.

The staffing story is a non issue – the independents will have access to more resources at the PBO and parliamentary library, so why should they have more personal staff than a shadow minister or even an actual assistant minister?