In a strong field, we may have a new contender for the biggest National Party rort yet — the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has found that 65% of a $1.1 billion set of grants made under five rounds of the Building Better Regions Fund (BBRF) weren’t the ones that should have been awarded under a fair and open process. And, of course, they went to National Party and Liberal electorates — all in a program that, like the sports rorts grants, was meticulously designed to bypass safeguards against pork-barrelling and hide it from scrutiny.

The auditor-general’s report details the lengths to which the Coalition government went to create a program that pretended to be about objective assessment of applications, but was mostly decided by a National Party-controlled committee, which rejected departmental advice and instead based decisions on electoral considerations, particularly ahead of the past two elections.

And while the sport rorts scandal was about a program shifted to the Australian Sports Commission in order to take it beyond the reach of the existing rules around grant allocation, the BBRF, which is still continuing now in its sixth round, was run by the Department of Infrastructure — ground zero for some of the most famous rorts and scandals of the past two decades, including the original regional rorts, the wild overpayment to a Liberal donor for land near the new Sydney airport, and the notorious car park rorts administered by Alan Tudge.

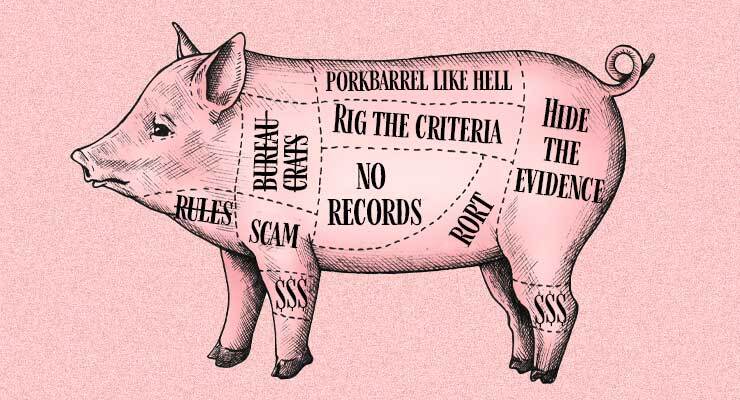

Infrastructure is subject to the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs), so here’s how the Coalition planned to get around them:

- Don’t let bureaucrats decide. All decisions about the annual round of grant applications were made by a panel of Coalition politicians chaired by a senior Nationals MP, which would consult with cabinet. This meant then deputy prime minister Michael McCormack for the crucial round at the end of 2018 that decided projects ahead of the 2019 election, and Barnaby Joyce for the late-2020 round that would make decisions in the run-up to the 2022 election — which Scott Morrison was considering holding in later 2021.

- Rig the criteria. While the department called for applications to be assessed based on a set of published criteria, the final criterion was “other factors”, which had some examples but was undefined and left to the ministerial panel. Some of the examples of “other factors” included “the Australian government’s priorities” and “community support for projects, which can include support from local MPs”.

The ANAO concluded “this factor was a key consideration across all previous funding rounds. While its wording suggests that the confirmation of community support would be evidenced through the application process, the ANAO’s analysis is that such support, particularly from parliamentarians, has been largely coordinated outside the application process by the chairs through their offices, and some members of the panel”. - Ignore any attempts to impose good process. The Department of Finance actually queried why Infrastructure had added this “other” criterion, and was fobbed off. The result: according to the ANAO, “the ministerial panel has increasingly relied upon the ‘other factors'” as each round went by. The result is obvious in terms of grants that weren’t approved by the department but got funded anyway.

- Hide the evidence. Under the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines, the minister for finance must be advised if a minister decides to approve an application that has been rejected by their department — thus creating a paper trail. How did they get around that? The ANAO pointed out that for rounds three and five — which were the preelection rounds — “rather than clearly identifying which applications should be successful up to the limit of the available funding, Infrastructure recommended the panel select from a ‘pool’ of projects … The significance of the changes made to the department’s approach was that, for the fifth round, there would be no circumstance in which any of the 528 applications seeking $761.4 million in grant funding that had been assessed as representing value with relevant money would need to be reported to the finance minister”.

- Don’t keep proper records: “Appropriate records were not made of the decision-making process. While not good practice in the first round, the record-keeping practices for the decision-making process deteriorated significantly in later rounds.”

- Pork-barrel like hell. The ANAO: “the Liberal Party and ALP held the greatest number of electorates associated with eligible applications (on average, each had 24 electorates, or 35% of applicable electorates). Funding outcomes were more favourable for applications from Liberal-held electorates, which received twice as many grants per electorate, with average funding per electorate being between $1.6 million (round one) and $3.1 million (round four) more than the amount awarded to ALP electorates; while the Nationals accounted for fewer electorates (16 in each round or 24% of applicable electorates), applications funded from these electorates outperformed those in Liberal Party and ALP electorates in terms of both average number of grants and value of grants.”

The lesson? You can tighten the rules around grant allocation all you like, but a determined rorter will always find a way to get around them. The only fix is to get politicians out of grant allocation entirely. They just can’t be trusted. Especially not the Nationals.

Thanks. Another sickening chapter in the endless saga of looting and pillaging from the public purse. As ever, those responsible are insisting the rules were followed and no laws were broken; as if that’s all right then. The claim is almost certainly true, in letter if not spirit, and is the worst part of the whole scandal.

Yes. So- called conservatives who have no respect for precedent or convention .

Government can be largely automated. Do we really need untrained politicians at all?

The administration can be, up to a point, and with the increasing capability of AI and so on no doubt will be except where ministers want to stick their oar in. (The results can be abysmal, as Robodebt proved, when it is automated by malign idiots.) I’m far less convinced automation can replace the guiding mind or minds in government that decide policies, priorities and so on. So, with something like allocating government grants it might be possible for ministers and their staff to devise a set of criteria, get parliament to agree and then have a largely automated process to compare applications against the criteria. That might still leave plenty of work for others, for example getting corroboration to confirm the information given in successful applications. That still leaves ministers deciding the criteria. Also parliament might not get any say if parliament has already passed legislation giving ministers a free hand to decide such things (which is often the case unfortunately thanks to the rapid growth of enabling legislation in the last 100 years).

Is that pretty much what you meant?

As far as I can see the main problem with our politicians is not so much their lack of training as the way they are selected to be candidates by the main parties and the way elections inevitably favours the corrupt. The parties with access to power are subject to irresistible temptations to sell their power and influence because they gain great advantages in elections by doing so. The ease of corrupting our politicians is, I believe, the principle reason the ruling classes are comfortable with this system of government. They control the government, not the voters. That’s why I would like to replace our elected parliament with one where our representatives are chosen at random at regular intervals from all our adult citizens. The representatives would of course be at least as untrained as before, but they would not be corrupt, it would be hard to corrupt them before they leave, it would be nearly impossible to corrupt enough of them to make a difference and they would not be concerned about being re-elected.

That would be the legislature. We could still elect a party to run the executive since we need some way of setting a direction to the government, but that executive would have to present every bill to a parliament it did not control and which is genuinely representative of the Australian people. That should ensure the executive cannot get away with anything too outrageous, unlike now when it usually controls parliament and need not be at all concerned about the public.

ICAC

Why?

It seems the ANAO has already set out the facts. Nothing suggests any rules were broken, and it is almost impossible to believe that any inquiry will find evidence of illegality. So what purpose would be served by another inquiry going over the same ground conducted by some federal integrity commission (I assume that is what you are referring to, not the existing NSW body)? Isn’t it time for some action, such as passing laws that makes this sort of thing a crime, not just another iteration of inquiries?

Consequences would be nice.

Stop the Gvt funding until it is a clear and useful project/ not for profit, which will be for profit for someone, just like the NDIS.

And for this outrageous malfeasance the consequences will be…. what? A significant number of these crooks were rewarded with another term in office.

We but await a Federal ICAC with

Strong compulsory powers to appear before such a body, giving no wiggle room to legal sleight of hand.

Retrospective powers broadening a statue of limitations which will enable such a body to track back on matters deemed actionable.

Specific protection for whistleblowers with heavy penalties both federal and state bodies as well as companies, individuals and organisations that act to suppress or penalise whistleblowers

Having developed and managed a multi-million dollar R&D grants program in the past, I am personally appalled and offended by the behaviour of these cynical shysters.

However, I believe that there is a misconception at the heart of this that Bernard Keane’s otherwise accurate article perpetuates. It revolves around the powers of the Minister under an Act, such as the Australian Sports Commission Act (ASCA) 1989. Allow me to explain in depth, as this is important, going forward:

Section 11 of the ASCA States:

“Minister may give directions

(1) Subject to subsection (2), the Minister may give written directions to the Commission with respect to the policies and practices to be followed by the Commission in the performance of its functions, and the exercise of its powers, and the Commission shall comply with the directions.”

Section 11 then goes on to say what the Minister must do to make these “directions” fully compliant, particularly with regards to written notification of the Board and Parliament.

It would seem that the Minister (Bridget MacKenzie) assumed that Section 11 gave her open slather to direct the Commission to fund whomever she pleased. Maybe if it came to a court of law, she might win, but the “accepted practice” relating to these words is far more restrictive.

Similar words to Section 11 can be found in many, if not most Acts of Parliament that establish a Corporate entity, especially those with “Money granting” powers. These words are generally meant to enable the Minister, as the representative of the peoples’ will, to suggest changes to selection criteria that enable the funds to best reflect contemporary needs. An example would be the need for more women’s change rooms in sporting arenas that have seen recent increases in women’s participation, such as AFL and soccer.

The “normal practice” would be that the Minister writes to the Chair, bringing these perceived needs to their attention and “directing” the Board to consider how selection criteria might be changed to better reflect this new need. The Board would then consider the request/direction and adjust the criteria if they saw fit and it was technically possible. The reporting of all of this would then be transparent to the public and the public would then be satisfied – notwithstanding that all requests may not be met.

The foregoing is dramatically different from the interpretation taken by the “Porkbarrellers”. It would seem that their interpretation was that they could tell (direct) the Commission to fund particular requests on the whim of the Minister.

Public “Corporations”, which have been established under Acts of Parliament have been developed, over time, to provide timely response to public need by combining some private sector features while remaining publicly accountable. They are not private entities that serve at the whim of venal politicians.

Clear it now is.