In the 75 or so years since World War II ended, wars in general have been smaller and more contained.

The fighting in Korea, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Afghanistan, Iraq (twice), the Balkans, Libya, Syria and even Vietnam was always devastating for those involved but the conflicts remained more or less local, rather than spreading around the world, or even through regions, forcing nations to choose one side or another.

Russia’s months-long war in Ukraine has already indirectly drawn in much of Europe and the US. The world has spent billions supplying the beleaguered nation with weapons and imposing sanctions on Russia. International forces have yet to take direct action but NATO has deployed thousands more troops from both sides of the Atlantic, establishing multinational battle groups in Slovakia, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria.

Now, on the other side of the world, an increasingly bellicose China has been confronted with intense provocation on its doorstep, and from the superpower it sees as its greatest rival. Analysts fear all-out war is inching closer on two global fronts, many thousands of kilometres apart.

US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan has global leaders on edge: a furious China will almost certainly retaliate. Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister Xie Feng has said the US “shall pay the price for its own mistakes”. China started military exercises in waters around Taiwan today, a harbinger of actions to come.

Many analysts expect China under the power hungry Xi Jinping to invade self-ruled Taiwan sooner or later, potentially within the next 18 months. Xi, who is expected to win a third term as China’s supreme leader later this year, said in 2021 that “reunification” with Taiwan “must be fulfilled”.

China claims Taiwan is a breakaway province, but the democratically minded Taiwanese regard it as a sovereign nation: they will resist a Chinese takeover as much as they are able, for as long as they are able, with assistance expected from international players.

Pelosi’s long-heralded visit might throw petrol on this smouldering bonfire.

US President Joe Biden has declared three times that the US would use force to defend Taiwan if push came to shove, but in each case his statement has been walked back by his minders, who say the US continues to abide by the so-called one-China policy which recognises self-ruled Taiwan as part of China.

And yet even if Biden’s comments were “gaffes”, it seems he was speaking from the heart, with the long-term fate of 24 million Taiwanese in mind. The US public sympathises with his loyalties, a significant concern as he prepares for the hotly contested mid-term elections in November.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned this week that “humanity is just one misunderstanding, one miscalculation away from nuclear annihilation”. At the same nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty meeting in New York, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken noted Russia’s “reckless, dangerous nuclear sabre-rattling” in Ukraine, citing Russian President Vladimir Putin warning that any attempt to stymie Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would trigger “consequences you have never seen”.

These warrior words are likely to be just part of the Putin macho schtick, along with riding horses bare-chested through the wilderness, but the man is unpredictable and few would bet on his restraint and balance. This territorial expansion into Ukraine smacks of Putin’s rarely checked ego flourishing in a nation where he has muted all criticism, much as disparagement of Xi is a dangerous game in China (even references to lookalike Winnie the Pooh are censored, just in case).

Meanwhile, the terrifying consequences of war continue to metastasise around the world. As soon as bullets start flying and bombs start exploding, ordinary citizens are the primary victims, and the poor are hardest hit — and not just in Ukraine and Russia. Food prices are at historic highs, social welfare nets are buckling, and assets are plunging continents away from the epicentre of the conflict.

A World Bank report in May found the war in Ukraine has been disrupting trade and investment around the globe, reaching into unexpected corners of manufacturing and services and hiking up prices for food and fuel everywhere from Africa to the Pacific.

This conflict comes at a difficult time, with the world’s economy shaken by the years-long COVID pandemic and the ensuing recession. Rising inflation has pushed central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia, to bump up interest rates, which has increased economic pain and curbed growth and investment. An Asian conflict will make matters immeasurably worse.

If China invades Taiwan, for instance, the world’s trade in semiconductors will be upended: Taiwan manufactures more than 90% of the world’s supply of the most advanced of these silicon chips, vital for both civilian and military equipment. China makes as much as 75% of the world’s laptops; just as Ukraine grew 10% of the world’s wheat in 2010, and Russia provided as much as 45% of the natural gas imported by the European Union.

We live in an interconnected world. Much as globalisation has been derided by critics, most serious economists believe it has driven growth and development around the world for the past three decades, lifting billions out of poverty and relieving untold hunger and misery. War corrodes globalisation and spawns fear of risk, disrupting trade and investment and fostering nativists’ push for protectionism.

Belt-tightening and workarounds can cope with shortages, but it will only get harder for a world reeling from war on two fronts, along with a seemingly unquashable pandemic that continues to give birth to new variants, and the escalating effects of climate change: wildfires, floods and heatwaves.

What fabulous news: Climate Armageddon will be trumped by nuclear Armageddon! Is humanity really this collectively stupid?

Probably, yes! Humanity has been sold the myth of economic growth because of globalism, globalism of an increasingly nationalistic political world. I seem to recall the prophets and shaman of neoliberalism claiming that globalism (ie the process of surrendering your national autonomy to concentrated production is some other nation) was going to brings the world’s peoples together. Is there any claim of neoliberalism that has not been conclusively proven wring by actual experience.

I think it was John Ralston Saul that wrote that over 80% of what the WTO counts as international trade is purely the cross-border movement of money, capital. Often 20% that is constituted by the cross-border movement of goods and commodities, 60% of that trade is the movement of good within a single corporate group albeit across borders. That means the 40% of 20% is what most people would consider international trade. Globalism, like everything to do with neoliberalism is a disaster for humanity and a triumph of social and wealth inequity because that is how it is designed. It just the PR that is opposite to that, what many would call lies.

Wow more right wing tosh. Putin is quoted but not the equally agreesive US Secretary of Defense. Again this selective reporting and demonisation of one side, weakens journalism as a bulwark against propaganda. Read Jeffry Sachs about US provocation over many years to see who the real culprit is.

So many adjectives, so little reality – like a cake that is all icing, no flour.

If this piece has been paid for out of our subscriptions I want my money back.

I would go further. Under Australia’s conditions of oligopoly what is needed to drive productivity is to lift wages first, thus forcing the oligopolies to seek expanded markets and/or invest for increased productivity to maintain profits. To get that to also flow to consumer prices you will be aided by aggressive market regulation. Centralised wage fixing was an important driver of rises in productivity and higher standards of living all through Australia’s history but the brilliant ignoramus Keating drank the Stone Kool-aid and dismantled most of it.

Agree AP7 except for the Keating comment. He didn’t actually do it but opened the door (As I feared at the time.) and allowed the Lying Rodent into the pantry to the ongoing demise of working men and women of Australia.

Be careful what you wish for. When the code words “increased productivity” don’t mean plain, old wage cuts they tend to mean automation – which inevitably leads to job shedding

When the boss said to the foreman “That machine will do the jobs of ten men!” he was asked “How many widgets will it buy?”

A simple equation that is far too complex for economists & other biz boosters.

I agree AP 7, especially with the Keating comment! He and Hawke did the ‘dirty work’ that the Libs would have had great trouble getting away with.

Thanks to you and all the replies. To my embarrassment I’ve actually posted under this article when of course I meant post under this article //uatcdn.crikey.com.au/2022/08/03/problem-isnt-productivity-its-corporate-power/#comments

There are no angels. In pursuit of balance I’ll mention that IBM manufactured and sold the machines to the nazis which enabled them to track down all those jews. America is such a power that, in the absence of business opportunities she can make them for herself. And propaganda is such a power that we will believe.

Meanwhile Gaia simmers – and plans her next move.

What? No mention of Ford motors in German WW2 tanks?

Gaia doesn’t plan. It seeks entropy. Constantly. Everywhere.

We need to talk about where we, h. sapien, is at, in terms of our decay, our descent back to where we came from, and what we intend to do about it.

Looks like Ben Elton was on the money with Stark.

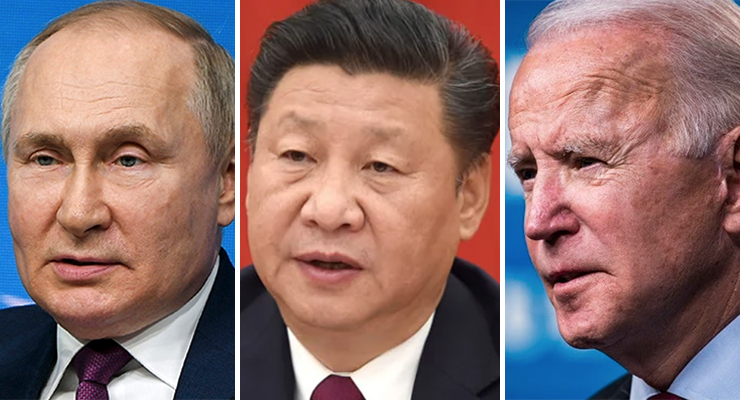

Anyone else notice the lack of gender diversity in the war mongers pictured above?