One of the few genuine reforms that might emerge from this week’s jobs and skills summit is a partial restoration of industry bargaining, via multi-employer agreements and even sector-wide pay claims.

Business groups are lining up to attack the idea and invoke the bad old days of the 1980s, although the Business Council of Australia (BCA) is offering an open mind (it seems the penny has dropped that, even under the Coalition, relentless hatred of unions and constant demand for company tax cuts have led it into a neoliberal dead-end).

That the BCA isn’t instantly dismissing the idea — and that the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) is already working with small business on the idea — reflects a fairly fundamental change even without any progress on Thursday and Friday.

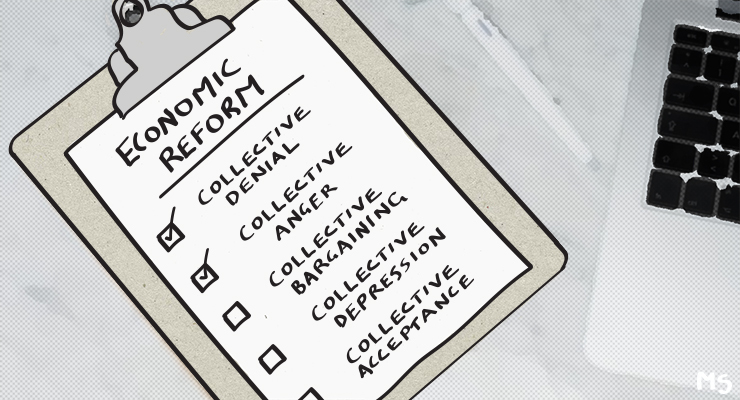

For 30 years, since the Keating government introduced enterprise bargaining with the support of Bill Kelty at the ACTU, the direction of industrial relations policy has been away from collective bargaining to individual contracts. The high point of the push was the disaster of WorkChoices, which helped end the Howard government and caused a significant fall in labour productivity — exactly as Treasury warned Peter Costello it would.

Consistent with the broader thrust of neoliberal policymaking, the relentless push to destroy collective action by workers and atomise them in industrial relations law — first to enterprise-level agreements, then individual contracts — was always justified by the claim that it would increase productivity. In fact, labour productivity growth has more than halved since the introduction of enterprise bargaining, amid a broader slump in productivity growth that was only temporarily reversed under the last Labor government. Under the Coalition, productivity growth fell back to near-historical lows and at one stage ceased altogether.

As Crikey has noted before, what productivity growth existed was wholly co-opted by businesses, with none of it shared with workers via wage increases or, now, price restraint. The growing power of corporations in industrial relations was accompanied by growing power in markets and in policymaking, and corporations readily exploited such power in all three.

If the individualisation of industrial relations failed to deliver productivity, it delivered the other goal — curbing the bargaining power of workers and unions. While wages growth lifted after Labor overturned WorkChoices, under the Coalition it plunged to record lows, leaving workers with no real wages growth between 2013 and 2021, and now delivering massive real wage cuts.

While there’s now common agreement that the enterprise bargaining system is broken, the view from employers is that if systemic protections built into the Fair Work Act were voided to make striking agreements easier, they’d be much keener on agreements and might stop simply letting their workers default onto award wages (a handy weapon businesses have developed over the past decade to deal with workers insisting on decent pay rises).

But what the broken system demonstrates is that you can’t constantly empower businesses at the expense of workers while maintaining fairness at the same time. One mitigates the other; attempts to address the tension generate an overcomplicated system that delivers stagnation both for productivity and wages.

Multi-employer agreements, and especially sector-wide bargaining, would begin rebalancing the power between workers and employers in the direction of the former — finally.

It points to a theme that won’t attract sufficient consideration before or at the summit — how much of our current economic challenges reflect the power structures created by 30 years of neoliberalism, which have delivered an economic environment heavily tilted toward the interests of corporations and their shareholders, not just in industrial relations but in markets, pricing, the environment, and in policymaking itself.

Is the wheel finally turning after decades? Very powerful, and very wealthy, forces will be keen to prevent it.

Oh dear, again and again, we have this discussion. It is not impossible to treat workers well and the benefits to the business are amazing.

Our first retail business venture, an antique shop at Kilcoy, could only be described as a financial disaster, although we had a lot of fun. Only employed one or two workers from time to time, but paid them over the award.

In order to feed ourselves we opened a coffee shop next door a move which worked well.

Got out of antiques and a few months later opened a franchise furniture store at Caboolture and later moved to Morayfield.

Here we had up to six people working at any one time, mainly fulltime employees.

So we paid these employees over the award, took them and their families out to dinner every few months, but, and this is the most important one of all, whenever we were thinking of making changes to our business operation, we always asked their advice, and took it. So, in return, they made us a lot of money.

Our sales went from $179,000 the first year to $1.2m the fifth year, all because we treated our workforce well..

Needed to restore some balance. The employers / owners have had a field day for 10 years – record profits and screwing employees. When I was a CEO years ago, fairness was an essential ingredent of a profitable company and a productive workforce.

The idea of addressing the power imbalance is attractive but the core issue IS a culture where business and labour fight it out with one sometimes on top of the other.

So – sure take back some/all/total control but it will only be temporary.

The culture of manager / executive plunder of organisations funds as “normal” or “deserved” needs killing off. It’s endemic in the anglo west along with “shareholder value” as the only important metric.

Capital stomping on labour has been in the area of diminishing returns for a couple of decades. It’s counter productive especially in large organisations.

Changes to bargaining necessitate changes to the right to take industrial action. Current law effectively prohibits strikes: all contrary to the ILO Conventions. Let’s hear the ALP sing that tune

The problem for the LNP is that they dont consuder employees as people. They are a resource like electricity or a vending machine. If you dont consider workers as people its easy to just think in terms of screwing them with the consequent resentment that goes with the that attitude. As is shown in some of thed other comments if you treat people as people you magnify what you get back.

I think it’s no coincidence that you hear some allies of business, inc. existing & former LNP MPs, speaking via old eugenics’ trope (libertarians are joined at the hip with), not of race, but workers should know their place &/or deserve any bad experience; up there with their demands for more e.g. ‘quiet Australians’….. hardly induces motivation to be competent, innovative, empowered and responsible.