A pharmaceutical industry representative once told me that the United States effectively subsidises other countries’ health systems because of its high prices for medicines. Drug companies, he said, can “go easy” in other markets because US profits are so healthy.

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act in the US will reveal if he was right. In fact, industry reaction to the part of the law that enables Medicare — America’s largest health insurer — to negotiate the price of some drugs based on their clinical benefit sets up a good test of the nonsense spouted by all vested interests when sensible regulation threatens profits.

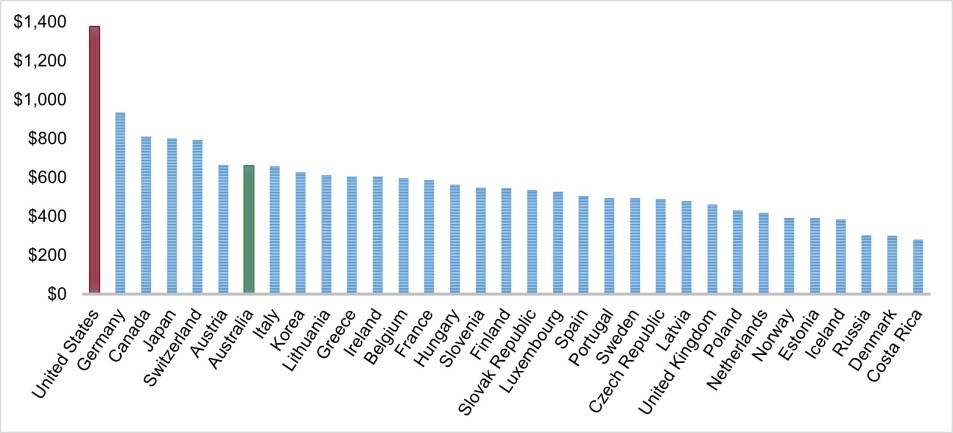

Americans do pay much more for pharmaceutical products than the rest of the developed world (see chart). The main reason is higher prices (consumption is on par with other countries). Prices are high largely because Medicare is prohibited by law to negotiate them. Effectively this means pharma can charge whatever it feels the market can bear for a product regardless of its clinical value.

This prohibition has set the US apart. Until now.

Even though the changes are very modest — Medicare will be allowed to negotiate on 10 drugs in 2026, 15 in 2027-2028, and 20 drugs in 2029 and beyond) — the industry isn’t happy. Why? Because like any financial negotiation, size equals clout. With more than 60 million enrollees, Medicare is America’s biggest insurer. Higher prices boost profits directly and have a spill-over effect because the Medicare price serves as a benchmark for smaller, private insurers. (No insurer wants to be the one that doesn’t provide a cancer drug, no matter how expensive or beneficial.)

This is why the supply side of health care (providers, clinicians, hospitals, drug companies) much prefers a fragmented insurance market, and detests consolidation on the demand side, including insurer-provider entities.

The prohibition was also the jewel in the crown of epic lobbying — more than US$5 billion over 25 years and by far the most out of any industry (see chart below). Little wonder they feel a little ripped off.

Actually, the lobby isn’t just unhappy — it’s seething. In a bizarre, threatening letter to Congress (including bizarre political threats), the peak body warned that “passing the legislation would lead to fewer treatments and cures — particularly for tough illnesses like cancer and Alzheimer’s disease”.

This claim not only has an unpleasant whiff of extortion. It’s also easily discredited. If the current system is so good, why don’t we have a cure for Alzheimer’s? (In fact, we might have if the money spent on lobbying and advertising was instead invested in actual research and development.) Yes, drug discovery and development are expensive and risky, and because we’ve outsourced most of both to capital, a decent return on investment is important. But the claim that price negotiations will result in fewer “good drugs” can be contested for two reasons.

First, linking the price of a drug to its performance will likely result in better medicines, not worse ones (as predicted) because the current arrangements reward mediocre products. The new ones will incentivise more effective and beneficial ones. And guess what? If price is linked to benefit, profits won’t suffer!

Second, returns in the pharmaceutical industry are very handsome compared to others (only tobacco is higher!). What’s more, profits have been maintained despite industry productivity (measured in new drugs per dollar of research and development) plummeting in recent decades. In other words, patients and taxpayers have been subsidising the shortfall.

Boil it down and the entire argument is an admission that the industry can’t deliver as many good products, which is perhaps why they resort to bullying Congress into vetoing sensible, evidence-based regulation.

The industry also claims that the changes will drive up prices around the world as companies seek profits in other markets. This is laughable. It just seems inconceivable that highly sophisticated enterprises — most of them listed companies — would leave money on the table in Europe or Australia just because revenue is so good in the US. Shareholders would certainly want to know more if this were true.

In fact, other countries, including Australia, are likely to benefit from one of the world’s largest health insurers turning its attention to the actual value of expensive medicines. Payers such as our own Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme will be watching closely (although pharma will probably ensure that prices are kept under wraps). In any case, the changes will embolden payers to negotiate harder. Patients and taxpayers will be the beneficiaries (a good thing given our rising out-of-pocket costs).

What’s interesting is that the dire predictions of pharma are no different to interests fighting regulatory change. Recall big tobacco’s convulsions when fighting the introduction of Australia’s (highly successful) smoking laws. Then there are the extractive industry’s ongoing efforts to block, hinder and water down meaningful action on climate change.

Time will reveal the direct consequences of drug pricing on those needing and paying for medicines. If, as many expect, the effect will be positive (including for pharma if it pulls up its socks), the broader lesson will be this: ignore the threats of vested interests and just get on with good public policy.

If nothing else, it’s nice to see the public interest winning for once.

This article was updated at 8.48 pm on September 13 to correct test accompanying the first chart.

Big Pharma, like oil and tobacco, has long operated as an untethered global mafia for far too long. If Pharna claims a drug must be priced at ‘x’ because of the research and development costs, what would be iniquitous about forcing Pharma to justify that claim with real data. Given that drugs are a crucial component of the social service provided by medicine, why it is allowed to operate with such opacity? Because of its global spread makes it beholden to no government, until now it seems. And look at the petulant reaction to the modest US price controls.

Big pharma has always scammed us. They easily bully governments into paying rediculous prices for drugs, possibly with incentives to the various decision makers. I would love to see a doco on the tendency of big pharma to produce hideously expensive drugs to reduce symptoms but rarely drugs that can cure anything. I have been an asthmatic for 65 years and paid a fortune in that time to big pharma but never been cured. The drugs only manage the symptoms. Like any parasute it is in their best interests to keep the host alive. Hence I believe big pharma is in the business of making sure we are all sick all the time, buying their drugs, never getting better, never being cured either.

Bit like saying isn’t it terrible that we have to keep buying petrol to keep the car going . So if the machinery is defective and can’t be fixed what is wrong with buying things that keep it going?

It’s nothing like that at all. The original Chinese medicine involved regularly seeing a doctor to keep you healthy. If you got sick, you stopped paying because doc wasn’t doing the job properly.

Fuel is of course a massive Rip off.

I don’t agree Desmond. Fuel for humans is food and water — nobody expects a product that enables us to survive without food.

The problem is that pharma companies have a prudential obligation to maximise profits. That’s why a pricing model that financially rewards more beneficial drugs is so important, and why this ban on price negotiation is imo a large factor in the productivity loss across the industry.

“…the extractive industry’s ongoing efforts to block, hinder and water down meaningful action on climate change”

Let’s get on the same side with our miners – and indeed all of Australia’s primary industries. They are all heavily dependent on fossil diesel fuel. Without being offered alternative fuel, of course they will fight to be heard. However, over the last 50 years the concept of clean synthetic fuels has been aired but never significantly funded. Only the hopelessly ignorant would suggest that batteries would suffice. If we are incapable of offering a solution, we should be promising to find one. When it comes to decarbonisation, we should supplying all parts of the economy with nonfossil power.

Article – Completely out of focus. The focus should be on the insurers how they will deprive society of the benefits of Pharmaceutical progress – it is not big Pharma who will be screwed it will the small companies who develop progressive drugs that will not be able to recoup their costs and insurers will screw them- Big Pharma is big enough to defend itself.

The Pharmaceutical industry is the only industry that develops products for human benefit, albeit at a a profitable level. Compare that to the “defence” industry makes money how to kill people more efficiently and cost effectively.

So back to the beginning – why hand power to the Insurance industry with their track record?

Hi Desmond – Medicare (US) is run by the government.

The USA govt/taxpayers paid Moderna $100 million for research/testing of the covid vaccine plus allowed patent and intellectual rights to the company. Producing 5 more billionaires from this action. (Forbes articles – apology from me for no date on publication date).

There’s also the question if the American diet producing ever increasing numbers of people with diabetes, kidney, heart and opiod addiction. All good for continued profits – no cures but constant intake of medication.

Any attempts to change diet and lifestyle runs into “personal choice” and the agribusiness models of continuous consumption. I’m waiting for the breakthrough research for the obese population to lose a kilo or two, then keep taking this med forever.

Corporates have too much influence to the detriment of the ordinary American.